The Exclusion of Migrant Women in Africa: Access to Safety and Security

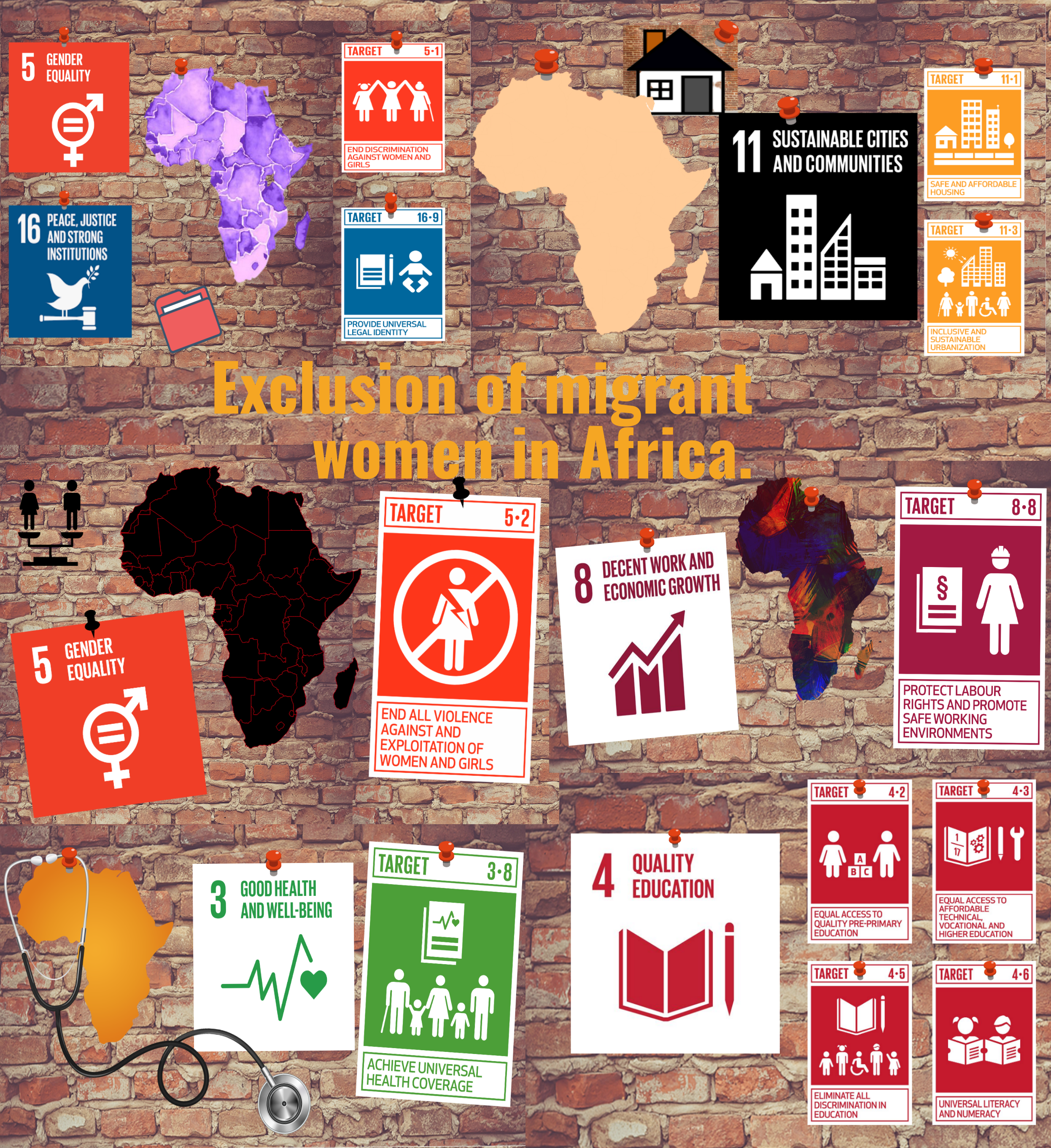

This article is the latest and final contribution to the series about the exclusion of migrant women in Africa. Through the article, we will examine the difficulties women on the move experience to be safe and secure. As mentioned in our previous articles, migrant women often go through many hardships regarding access to health care, housing, education, identification documentation, and the labour market [i, ii, iii, iv and v]. Even though these topics have been well covered previously in this series, they are also important in relation to safety and security. The article will therefore examine how the lack of access to some of these services are intertwined with safety and security issues like violence and crime. It will then address Covid-19 and evaluate whether their access has been affected by the pandemic. Finally, the article will present a summary of migrant women in Africa and their access to safety and security.

1. THE DANGEROUS REALITY FOR WOMEN ON THE MOVE

Although being safe and secure can be a challenge for women who are not migrants, being a migrant tends to exacerbate the challenge. From the moment women leave or flee their homes, they are being exposed to many gender-based safety issues. Gender-based violence (including sexual abuse, physical violence, forced sterilization and contraceptives), xenophobic attacks, deportation, exploitation, and human trafficking are some of the threats many migrant women can face [1, 2, 3]. The movements of migration are constantly changing and that can be a challenge for transit and destination countries while trying to provide protection [1]. Migrants, especially female migrants, are in need of protection from exploitation, violence and discrimination. According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), all humans have the right to live in safety with the same level of protection, no matter who we are or where we are [19]. However, this is not an easy job with irregular migration and changing migration patterns, as well as the prevalence of discrimination and xenophobia. This can relate to target 5.2 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to “Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation.” [4].

1.1 Forced or coerced sterilization and contraceptives

Lack of sexual and reproductive health care is considered to be one of the main causes of death, disability, and disease among women on the move, according to The Women’s Refugee Commission [5]. Furthermore, information about sexual, reproductive, and general health care is often not easily available for migrants, and language barriers tend to be a problem [1]. This can explain how health care is connected to migrant women’s safety and security. For instance, it has been stated that Somali women in South Africa have experienced language and cultural discrimination while seeking health care services [3]. Claims have been made that some of these women have been sterilized without their consent after being forced to sign papers in a language they do not understand [3]. Although there is not enough data to support the claim that forced or coerced sterilization happens more often to migrant women than to women in general, it has been recognized as a discriminatory act towards minority and indigenous women by the UN [6]. The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and regional courts have also addressed these medical interventions and states that “(..) they have been qualified as forms of gender-based violence against women that may result in physical and psychological harm and that may amount to torture or cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.” [6, p.9].

Priti Patal – a human rights lawyer with over 15 years of experience within this field - takes this a step further and argues that it is essential to assess whether women’s rights to be free from discrimination have been violated in all cases regarding forced sterilization [7]. She refers to several cases in Namibia where the Supreme Court found that the act was a violation of the women’s rights but decided not to assess the discrimination claims [7].

Another report from South Africa addressed Zimbabwean migrant women and their access to health care. The term “medical xenophobia” was used in this context, and it can be explained as an act where health care workers discriminate against foreigners and do not give them the same medical help as they give to locals [20]. Several of the women in this study had experiences of being injected with contraceptives without their consent. A statement from one of the participants gives a good example of medical xenophobia:

The nurses came, and they did not even ask me, they just told me to roll up my nightdress sleeve and I assumed they wanted to put me on the drip. When I saw her take out the implant package, I immediately told her that I didn’t want an implant. But she just continued, and she told me that the implant was for five years and it was going to keep me from giving birth in a country that was not mine. [20, p.18].

This example put a side, it must be mentioned that it can be a challenge to differentiate between medical xenophobia and a worsened health care system under pressure. Some of the experiences these women have had might not be unique to migrant women in South Africa. Nonetheless, forced or coerced sterilization, contraception without consent, and the lack of access to safe health care in general, can be considered as a threat to migrant women’s safety as well as an obstacle to reaching target 5.2 of the SDGs.

1.2 Human trafficking

A sudden need for money to get protection or help with transit can often lead to human trafficking, sexual favours, and exploitation [1]. According to the 2020 UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, 7 out of 10 trafficking victims globally are women and girls, and “migrants account for a significant share (..)” as the “traffickers pray upon the marginalized and impoverished.” [8, p.4]. The report shows that forced labour and sexual exploitation stood for respectively 77% and 20% of all detected trafficking victims throughout Sub-Saharan Africa [8]. The victims in North Africa were equally divided between forced labour, sexual exploitation, and exploitative begging [8]. Statistics from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) show that there was an increase in potential sex trafficking victims from Africa to Italy of almost 600 per cent between 2013 and 2017, where most of the victims came from Nigeria [15].

Migrants without documentation are especially at risk of being trafficked as they often are in need of employment. This is an example of how the access to both identification documentation and the labour market are intertwined with safety and security. The lack of necessary documentation can lead to difficulties getting a job – which in turn makes them an easy target for traffickers [8]. Trafficking itself is in direct conflict with target 5.2 of the SDGs and makes it a challenge to reach this goal.

1.3 Sexual abuse

Continuing with access to the labour market is the issue of sexual abuse. Migrant women often find themselves working in the informal sector or as domestic workers [9]. A study on female migrants in the informal sector in Ghana found that these women were at greater risk of experiencing physical and sexual abuse, and exploitation [10]. However, even though the risk of this happening is bigger in the informal sector due to the absence of regulation, there have been reports of harassment, physical abuse, and rape of migrants in the formal sector as well [1].

Access to identification documentation is also of relevance regarding sexual abuse. A report on immigration in South Africa tells the story of several African women who have been forced into sex to obtain documents or permits [11]. Sexual abuse can therefore be considered as the price these women have to pay to get a legal status document for security. In addition, migrant women who have been sexually abused, often fear to report these crimes as they do not have the right documentation to be in the country and do not want to risk deportation [14]. Again, this is in direct conflict with target 5.2 of the SDGs, when sexual exploitation is present. Gender based violence is prevalent in the DRC, particularly in the Eastern and South-Central Provinces [23] giving rise to migration on a large scale internally and across borders. As a way forward to combat gender based violence in the DRC the UN calls upon GBV actors to strengthen a holistic response to GBV survivors and increase capacity building of service providers, to “scale up prevention strategies including positive masculinity, risk mitigation efforts through the involvement of other sectors in the humanitarian response, community engagement and community resilience” and lastly to “ensure improvement of accountability to affected population, evidence based intervention towards assessments and monitoring and evolution” [23]. Furthermore, sexual abuse is often being connected to xenophobia - which will be the next topic to address.

1.4 Xenophobia

A growing number of African women are migrating to South Africa due to its higher level of gender equality and stronger economy, compared to many other African countries. A report by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) found that “Women migrants in South Africa encounter high levels of xenophobia at both community and official levels, including from government officials” [12, p.2]. The experiences these women have encountered includes verbal and sexual abuse, assault, stabbing, shooting, violence, and even death [12, p.25]. This has resulted in a low level of trust in authorities in South Africa among migrant women [13].

Some of the stories from South Africa involve migrant women being wrongfully accused of bringing HIV/AIDS to the country, stealing their husbands and jobs from South Africans, and result in migrant women being the target of brutal sexual attacks [14]. Although they do not have any official statistics to support this claim, the police have noticed an increase in rape whenever there is a wave of xenophobia [14]. Additionally, the ISS report also found that most female migrants considered gender-based or sexual violence to be one of their biggest threats as a result of xenophobia [12].

Xenophobia in South Africa is a common occurrence [20]. Although the term is often related to, and thought of, as violence and looting of foreigner’s property, it can also manifest as a structural or institutional problem [20]. Migrants can experience this type of xenophobia in areas like education, bank services, support from the police, the Department of Home Affairs, or as we saw in the examples above – in health care. Article 7 of the Universal Declaration of Human rights states that “All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law” [19] and similarly section 9(1) of the South African Constitution states that “Everyone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law” [21]. This applies to everyone within South African territory, including refugees, asylum seekers and all other migrants. Moreover, section 9(3) of the Constitution specifies that the state is not to discriminate based on amongst other things, gender, or ethnic or social origin [21]. Unfortunately, as the following court cases will show, progressive laws and practice do not always act in accordance with each other.

In the case of Carmichele v Minister of Safety and Security and Another (Centre for Applied Legal Studies Intervening) 2001 (4) SA 938 (CC), the victim was attacked by a man who was out on bail for attempted rape, while awaiting the court’s decision [22]. This man had a history of violent behaviour. Carmichele therefore sued the Minister of Safety and Security due to the police and prosecutor’s decision to release him on bail as he was a danger to women around him. She argued that they had a legal duty to protect her and referred to her constitutional rights. After losing the case in the High Court and the appeal in the Supreme Court, she eventually won in the Constitutional Court. As an organ of State, the Court found that the police had an obligation to protect all citizens in accordance with the Bill of Rights and not doing so would be a violation of their fundamental rights [22]. Although Carmichele is not a migrant woman, this example shows how difficult it can be to obtain safety and security rights you are entitled to in South Africa.

A case which involved migrants detained for deportation was Lawyers for Human Rights v Minister of Home Affairs and Others (CCT38/16) [2017] [23]. This case addressed the Immigration Act 13 of 2002 and the holding of migrant in detention for lengthy periods in excess of 48 hours without the right to in person contest the lawfulness of their detention before a court. Section 12(1)(b) of the Constitution states that “Everyone has the right to freedom and security of the person, which includes the right not to be detained without trial” [21]. In terms of section s 35 (2)(d) of the South African Constitution "Everyone who is detained, including every sentenced prisoner, has the right—… (d) to challenge the lawfulness of the detention in person before a court and, if the detention is unlawful, to be released" [21]. However section 34 of the Immigration Act prior to the Lawyers for Human Rights Case [23] allowed immigration officers to act in an unconstitutional way in the case of detention for deportation, by allowing for detention without out being brought before a court of law within 48 hours in deportation cases.

The Constitutional Court upheld the High Court’s Decision and found that “Section 34(1)(b) and (d) of the Immigration Act 13 of 2002 is declared to be inconsistent with sections 12(1) and 35(2)(d) of the Constitution and therefore invalid” in the Lawyers for Human Rights Case [23, para 73]. This case was a great win for migrant’s rights to freedom and security.

This fear or hatred of anyone foreign has also had in impact on migrant women’s living conditions in South Africa as they have difficulties obtaining adequate housing [12]. Hence, many migrant women live in unsafe accommodations where the risk of being exposed to xenophobic attacks is present. Due to all the security challenges xenophobia can cause - despite there being laws in place to prevent it - it is making it difficult to “eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls” in the region [4].

2. COVID-19 AND ITS EFFECTS ON MIGRANT WOMEN’S SAFETY AND SECURITY

Lockdowns and movement restrictions due to the pandemic have changed the lives of most people in the world. It has also created a larger amount of vulnerable people. Migrant women were already considered to be a vulnerable group before the pandemic and are therefore facing even greater challenges and security issues now than they did before. One of the many effects Covid-19 has led to is higher unemployment. The Global Report on Employment suspects that this will lead to more trafficking in persons as more people are willing to take a risk to improve their lives [8]. Vulnerable groups are being affected the most by the pandemic and it is therefore not unlikely to assume that there will be a higher risk of migrant women becoming victims of trafficking [8].

Furthermore, organizations and law enforcement working to prevent human trafficking, or other types of gender-based violence, are facing greater challenges like limited funding, difficulties coordinating and planning activities, and reduced staff capacity [16]. Many nations have had to move personnel from several sectors to get more resources into stopping the spread of Covid-19 [16]. This may have a negative effect on all areas in society where resources have been removed. UN Women has similar findings and states that resources originally directed towards ending violence against women have been redirected towards immediate Covid-19 relief [18]. According to the UNHCR Global Report 2020, Covid-19 has resulted in an increased risk of both gender-based and domestic violence [17]. The report also points out that the agency has had difficulties providing medical assistance due to restrictions of movement [17].

In mid-2020, Ethiopian Women and girls were deported from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and then detained for deportation under awful conditions as a result of the pandemic and response of authorities [25, 26]. On the basis of unsubstantiated grounds of health risks without testing, Saudi Arabia and the UAE deported thousands of Ethiopian workers [25]. Then following a public outcry against deportations these were halted [26]. As observed in the access to healthcare post in the SIHMA exclusion of Migrant women series [ii]:

deportations were halted. However, many migrants were instead detained and remain in Saudi Arabia under appalling conditions under which overcrowding (eg between 300 and 500 women and girls in one room [27]), disease and lack of medical care for migrants, including women and girls, is commonplace. Pregnant migrant women and children are at serious risk in detention [28]. ‘Detainees say there are a significant number of pregnant women in detention. Roza, 20, who was six months pregnant at the time of interview, said there were 30 other pregnant women in her cell... None of the pregnant women Amnesty talked to or heard about were receiving adequate health care [28].’ Marie Forestier, from Amnesty International said: “Pregnant women, babies and small children are held in these same appalling conditions, and three detainees said they knew of children who had died. We are urging the Saudi authorities to immediately release all arbitrarily detained migrants, and significantly improve detention conditions before more lives are lost.”

It is clear the during the pandemic these migrant women’s rights to safety and security were far from protected. More recently in June 2021 Ethiopia migrants in Saudi Arabia were arrested on mass in waves of arrests cracking down on documented and undocumented migrants [28]. In recounting arrests on 15 June 2021, Jafar, a documented migrant, recounted the events being “like an invasion, with police cars surrounding the whole block and police… beat and arrested women and told bystanders not to film…” [28].

Even though there is not enough data to know the full effects of Covid-19 yet, current data leans towards there being a significant negative impact of Covid-19 on migrant women’s access to safety and security.

3. SUMMARY

African migrant women’s access to safety and security is not a matter of course. Many women and girls on the move are going through hardships and potential life-threatening experiences simply because they are female migrants. Unfortunately, gender-based violence, human trafficking, exploitation, and xenophobic attacks are a reality for many of these women. International initiatives and commitments like the Sustainable Development Goals have been put in place to change this. More specifically, this article addressed target 5.2 of the SDGs, to “Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation.” [4]. The discrimination and crimes that are being perpetrated against migrant women and girls prove that a number of African countries on the continent still has a long way to go to reach this goal. The pandemic has not contributed in a good manner, but rather increased the harm and potential risks for migrant women. International frameworks have made positive developments towards “gender mainstreaming migration related policies and practices” [12] and this should be mirrored and built upon in legislation and policy in countries across the African continent. It is important to promote rights-based, gender-sensitive migration policies [13] to reduce migrant women’s exclusion from rights realisation and reduce the risk of violation of safety and security rights. It is even more important to ensure that these policies are being well implemented and followed in practice.

James Chapman and Victoria Jensen

SIHMA SIHMA

Project Manager Communications and Research Intern

References

- https://sihma.org.za/Blog-on-the-move/the-exclusion-of-migrant-women-in-africa-access-to-the-labour-market

- https://sihma.org.za/Blog-on-the-move/exclusion-of-migrant-women-access-to-health-care

- https://sihma.org.za/Blog-on-the-move/exclusion-of-migrant-women-in-africa-access-to-education

- https://sihma.org.za/Blog-on-the-move/exclusion-of-migrant-women-in-africa-access-to-housing

- https://sihma.org.za/Blog-on-the-move/exclusion-of-migrant-women-in-africa-access-to-identity-documentation-for-migrant-women

- https://undocs.org/E/CN.9/2018/3

- https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/sar-16.pdf

- https://sihma.org.za/journals/AHMR%206:1%20-%2002%20Turning%20a%20Blind%20Eye%20to%20African%20Refugees%20and%20Immigrants%20in%20a%20Tourist%20City.pdf

- https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5

- https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/event-pdf/Disaster-Preparedness-Reproductive-Health-Course-English%20%281%29.pdf

- https://undocs.org/A/74/137

- https://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40985-017-0060-9

- https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/tip/2021/GLOTiP_2020_15jan_web.pdf

- https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_743268.pdf

- https://sihma.org.za/journals/03%20Experiences%20of%20Female%20Migrants%20in%20the%20Informal%20Sector%20Businesses.pdf

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03057070.2016.1211805

- https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/sar-16.pdf

- https://issafrica.org/iss-today/woman-migrants-forgotten-victims-of-south-africas-xenophobia

- https://www.globalsistersreport.org/news/people/news/news/south-african-sisters-address-violence-against-migrant-women

- https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/07/562032-un-report-reveals-shocking-abuse-african-migrant-women-face-their-journey

- https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/2021/The_effects_of_the_COVID-19_pandemic_on_trafficking_in_persons.pdf

- https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/gr2020/pdf/GR2020_English_Full_lowres.pdf#_ga=2.170013862.765121926.1627289265-307189589.1623572923&_gac=1.251589876.1624430000.Cj0KCQjwlMaGBhD3ARIsAPvWd6hT9BUDc6bP_550nstza2DYBRvuDr6Xa8vr97-xSOhAkeQlsutO_v0aAoCtEALw_wcB

- https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violence-against-women-during-covid-19?gclid=CjwKCAjwuvmHBhAxEiwAWAYj-GfRkomfWBT1UQxvyktr_VIp0CnPnfE4D4fTHUJs2JguV4bgIxF6FhoCghsQAvD_BwE

- https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

- https://sihma.org.za/journals/1.%20Zimbabwean%20Migrant%20Women%20Health%20Care.pdf

- https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/images/a108-96.pdf

- http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2017/22.html

- http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2004/12.pdf

- https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/gender-based-violence-democratic-republic-congo-key-facts-and

- https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-thousands-of-migrants-head-back-to-ethiopia-after-deportations-as/

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-ethiopia-migrants-idUSKCN21V1OT

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/19/immigration-detention-saudi-arabia-during-covid-19

- https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/10/ethiopian-migrants-hellish-detention-in-saudi-arabia/

- https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/saudi-arabia-ethiopia-crackdown-migrants-thousands-despite-documentation

Categories:

Tags: