Exclusion of migrant women in Africa | Access to education

Continuing the Series on Migrant Women

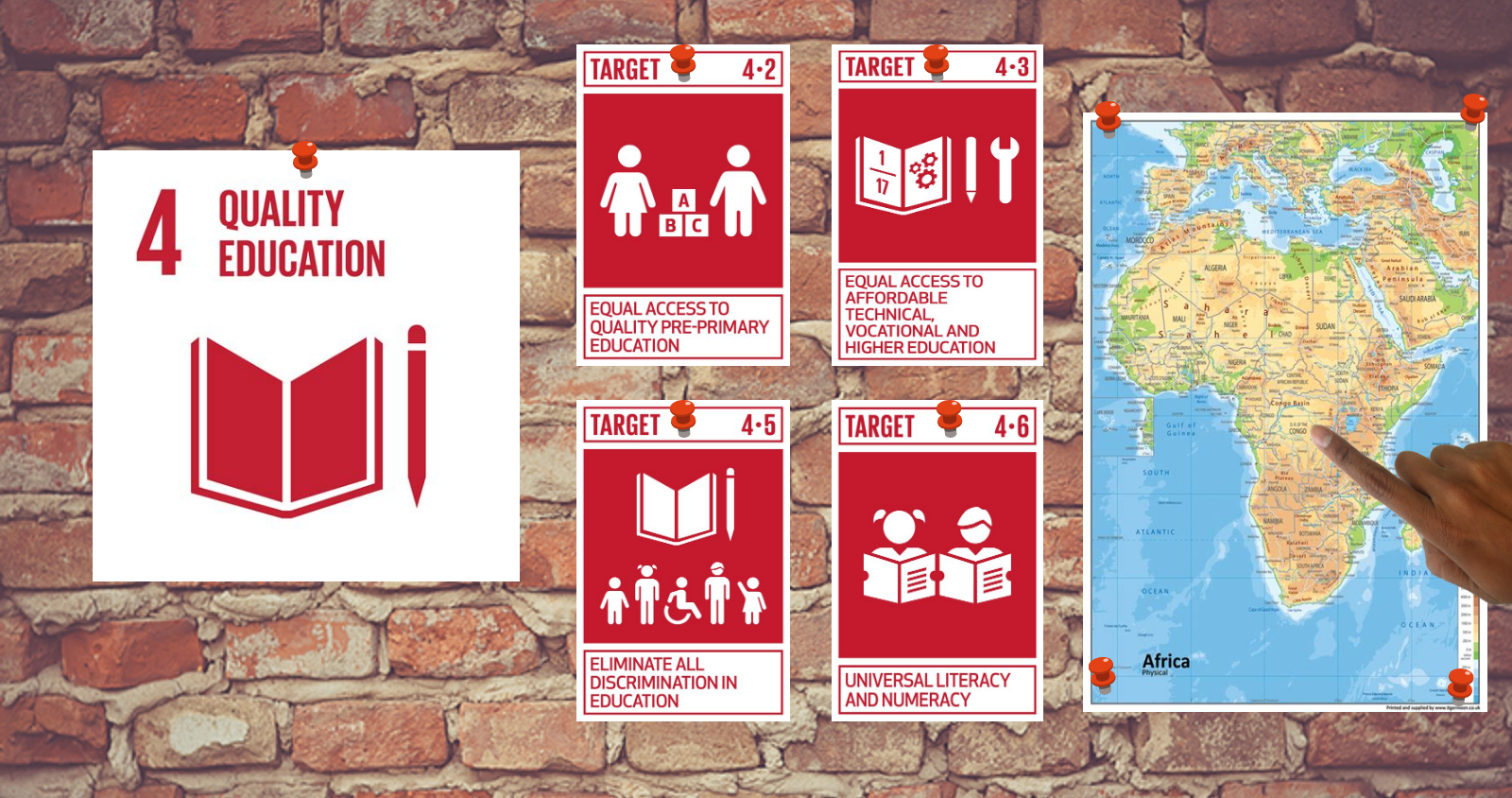

Continuing our series on the exclusion of migrant women, we are looking at the rather limited access to education that migrant women have around Africa.

The education of any child, boy or girl, is an undeniably essential and fundamental human right. However, for millions of women and girls among the world’s migrant, refugee and asylum-seeking population, education is not a reality. Migrant and displaced children face numerous obstacles accessing classrooms, including discriminatory laws, documentation requirements, detention, lack of educational facilities, school closures due to armed conflict and natural disasters, geographical inaccessibility of schools, school fees, language barriers and lack of access to information on their right to education [1]. In 2019, refugees were twice as likely to be out of school than other children [1]. Limited access to education intensifies the challenges to, and limits the potential of, women and girls on the move who are trying to rebuild their lives and protect themselves against further mistreatment [2].

While the crisis in education in many poor nations is not just a female issue, in most cases migrant and refugee girls are being educated at lower rates and are completing less education than boys [3]. There is a myriad of economic, social, and political benefits related to the increased access to quality education for these women and girls - including improving children’s and women’s survival rates and health, reducing population growth, increasing economic growth, improving women’s wages and jobs, protecting children’s rights and delaying child marriage, empowering women and reducing harm to families from natural disasters and climate change [3]. Empowerment through education is fundamental to preventing maternal risk. Girls and women with higher levels of education are more likely to have delayed and spaced out pregnancies, and to find medical support and care [4]. Between 25 and 50 per cent of girls in developing countries become mothers before they reach the age of 18 [4]. Education is not only informative, but also protective as it reduces girls’ vulnerability to exploitation, sexual and gender-based violence, teenage pregnancy and child marriage [5]. Ultimately, ensuring that migrant and refugee girls gain access to quality education is not only crucial to their own individual empowerment, but to the future prosperity of their families and communities [5].

Barriers for migrant women and girls to go to school

According the UNHCR’s report on refugee education, only 61% of refugee children have access to primary education, compared to an international average of 91% [2]. At secondary level, 23% of refugee children go to school, compared to an international average of 84% and in low income countries only 9% of refugees attend secondary school [2]. And at tertiary level, only 1% of refugees attend tertiary education whereas the global figure for tertiary enrolment is 36% [2]. While all people on the move face significant barriers to education, the situation in developing regions is much more dire [6]. For girls in developing regions, however, it is even tougher - in Uganda while there are nine refugee girls for every ten refugee boys enrolled in primary school, girls are only half as likely to enrol as boys at secondary level; in Kenya and Ethiopia while there are seven refugee girls for every ten refugee boys enrolled in primary education, there are only four girls to every ten boys enrolled in secondary level [8]. In contrast according to UNESCO [7], globally there were an equal number of boys and girls enrolled in primary education and secondary school in 2018. As one can see from these figures and trends that refugees have significantly less enrolment in and access to education and that as refugee children grow older, the gender gap in education itself grows.

One of the greatest barriers to both migrant and refugee boys and girls attending school is the cost of school fees, uniforms, books, and transportation - even small costs can become unaffordable for families on the move that are often denied the right to work [8]. However, by virtue of their gender, girls face serious and unique economic, cultural, and safety barriers. As an economic barrier, girls are at a disadvantage in terms of the losses of income and domestic duties that arise from the attendance of school [3]. Tasks such as the collecting of water or fuel, taking care of younger siblings or older relatives, and household chores are generally taken care of by girls. If a family has limited resources and must choose between which of their children will attend school, boys are often prioritized [3].

The issue of cost is further compounded by the social and cultural conventions that migrant and refugee girls have to battle - some communities believe that there is no need to educate girls [8]. In places where child marriage and teenage pregnancy are the norm, girls are either completely denied access to education or only attend until the end of primary school [8]. In terms of safety barriers, these girls face sexual and gender-based discrimination and violence in their communities, on their journeys to school, and at school itself. Compounding this, schools are made more unwelcoming for female students if there is a lack of access to sanitation, clean water and private toilets [9]. Menstruation can lead migrant and refugee girls in sub-Saharan Africa to miss up to four days of school every four weeks [8].

In South Africa, one of the biggest barriers to entry for young migrants and refugees hoping to attend school, is the documentation that needs to be submitted as a condition of enrolment [10]. While all children, regardless of nationality, social origin, or documented status have a fundamental and undeniable right to basic education in South Africa, learners were denied access to public schools, or were later removed from school as a result of a lack of documentation [10]. The policies and practices within South Africa were ultimately inadequate to protect and promote the realisation of the right to basic education for many undocumented migrant and refugee learners [10]. This unconstitutional denial of access to education due to being undocumented was challenged in Eastern Cape High Court by the Centre for Child Law and others (including 37 children) in the Centre for Child Law and Others v Minister Of Basic Education and Others case [25] On 12 December 2019, the court ordered the education department to admit all undocumented children into public schools in the Eastern Cape and provide funding for them [26]. The court also ‘ordered the department not to remove any undocumented children from school, including the children of immigrants in the country illegally and emphasised that the best interests of the child are considered paramount [26].

Refugee and asylum seeker children are often unable to obtain an official birth certificate or identity document as they have fled from fear or threat of persecution and are unable to seek assistance from their country of birth. Currently, stateless children are unable to access primary education or write matric examinations, despite the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recommending in 2018 that the State “ensure that all migrant, refugee and asylum-seeking children have access to education regardless of their immigration status” [11]. Migrants, refugees and asylum-seeking children in South Africa face significant challenges in accessing basic education as a result of a lack of clarity in the legal and policy framework. From what we have learnt so far, in these communities girls are even less likely to attend school than boys when the opportunity is available. Thus, in South Africa, these girls are at an even bigger disadvantage than in other developing nations where education is treated as a basic right for all children.

New challenges resulting from Covid-19 and the access to technology

Covid-19 will have long lasting consequences on refugees’ and migrants’ education in Africa, and especially for women and girls. According to UNICEF, the longer marginalized children are out of school, the less likely they are to return [12]. As access to school is curtailed, more children may drop out and some will be called to work to offset economic strains, potentially making a return to school after the pandemic subsides even more difficult [13]. While data may be insufficient to truly understand the long-term consequences of Covid-19, if compared with the Ebola epidemic, we can expect that many older children have been forced to drop out of school to care for younger siblings or frail elders [14]. Technology and online learning do not represent an appropriate coping solution for many migrants in Africa. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, where more than a quarter of the world’s refugees reside, 89% of learners do not have household computers and 82% lack internet access [15]. eLearning Africa’s latest study warns about the danger that the current crisis will ultimately increase the so-called ‘digital divide’ in education between those with access to technologies and those without [16], thus leading to increased inequalities, including gender inequality.

Women and girls are disproportionately negatively affected by the Covid-19 crisis in their access to education. Malala Fund found that marginalised girls are more at risk than boys of dropping out of school altogether following school closures and that women and girls are more vulnerable to the worst effects of the current pandemic [17]. They face potential harassment by fathers or uncles, have to take on childcare responsibilities and household chores, are at risks of child marriage and have less access to technology resources than boys to continue online learning [18]. According to the Ethiopia’s Women and Children’s Affairs Bureau, as of June, more than a hundred girls have been raped since the start of Covid-19 crisis in Addis Ababa due to the school closures [19].

What can we do? Examples of initiatives, need for policies

Interventions are required to attempt to overcome these barriers hindering refugee and migrant girls’ access to education - interventions that help make schooling more affordable, that help girls overcome health barriers, that reduce the time and distance to get to school, that make school more girl-friendly, that improve the quality of education, that increase community engagement, and that sustain girls’ education during times of emergency [3]. Setting up affordable, girl-friendly schools that are nearby is one of the first steps to actually getting girls to school. Donors and agencies looking to promote education in migrant, refugee and asylum-seeking communities, need to support policies that ensure that access to school is inclusive and equitable - schools must make space for girls [8]. After reviewing 146 social protection interventions aimed at improving education outcomes, UNESCO documented that some element of cash assistance to migrant and refugee families helped to underwrite the real and opportunity costs influencing whether or not families would send their girls to school [20].

In Tanzania, attendance doubled after the elimination of fees - the country eliminated fees for primary school in January 2002, and estimated that 1.5 million additional students, mainly girls, began attending primary school almost immediately [21]. In Kenya, providing free uniforms to orphans and refugee children reduced absenteeism by 7 percentage points, especially for girls [22]. In Ghana, a program that supplied sanitary pads and puberty education increased girls’ confidence and capacity to engage in the classroom during menstruation [23].

In countries like South Africa, where a lack of clarity of existing legal and policy frameworks and the lack of separation between the provision of basic services and immigration control results in undocumented learners facing significant challenges to accessing basic educations, the State needs to create an effective system of collaboration amongst and between relevant departments to ensure that no one is denied their basic right to education.

With migration and displacement becoming more and more a hot political topic all over the world, education is key to provide a critical understanding of the phenomenon and related issues. Education is a critical tool, not only for tolerance, but also in fighting prejudice and discrimination [24]. School curricula need more than ever to be inclusive of immigrants and refugees' experience and address the negative attitudes they face. Diversity in classrooms, while bringing its own challenges, offers great opportunities to learn from other cultures and experiences, and thus can help to promote cohesive societies in our globalized world [24].

Take a look at our previous blog posts of the series on migrant women’s access to the job market and health care services.

James Chapman, Nolwenn Marconnet and Christine Lalor

SIHMA SIHMA SIHMA

Project Manager Research and Communication Intern Research and Communication Intern

Resources

[1] Right to Education Initiative, 2020. ‘Migrants, refugees and internally displaced persons’, Right to Education. https://www.right-to-education.org/migrants-refugees-IDP

[2] UNHCR. 2017. Education Report - Left behind: Refugee education in crisis. https://www.unhcr.org/uk/news/press/2017/9/59b6a3ec4/unhcr-report-highlights-education-crisis-refugee-children.html

[3] Sterling, G.B., & Winthrop, R. 2016. What works in girls’ education? Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

[4] UNESCO. 2011. Education counts - Towards the millennium development goals. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000190214

[5] World Bank. 1993. Returns to investment in education: A global update. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/468021468764713892/returns-to-investment-in-education-a-global-update

[6] UNHCR. 2016. Global trends report. https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2016/

[7] UNESCO. 2020. Global education monitoring report. https://gem-report-2020.unesco.org/gender-report/

[8] UNHCR. 2020. Her turn: It’s time to make refugee girls’ education a priority. https://www.unhcr.org/herturn/

[9] World Bank. 2005. Toolkit on hygiene, sanitation and water in schools. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/339381468315534731/pdf/410300PAPER0Hygiene0toolkit01PUBLIC1.pdf

[10] SAHRC. 2019. Access to basic education for undocumented learners in South Africa. https://www.sahrc.org.za/home/21/files/SAHRC%20Position%20Paper%20on%20Access%20to%20a%20Basic%20Education%20for%20Undocumented%20Learners%20in%20South%20Africa%20-%2012092019.pdf

[11] CESCR. 2018. United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Concluding observations on the initial report of South Africa as approved by the Committee at its 58th meeting, held on 12 October 2018.

[12] United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2020. ‘Education and Covid-19’. https://data.unicef.org/topic/education/covid-19/

[13] You et al. 2020. ‘Migrant and displaced children in the age of COVID-19: How the pandemic is impacting them and what can we do to help’, Migration Policy Practice, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2020, pp. 32-39. https://data.unicef.org/resources/migrant-and-displaced-children-in-the-age-of-covid-19/

[14] Human Rights Watch. 2020. ‘COVID-19 and children’s rights’. Https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/09/covid-19-and-childrens-rights-0#_toc37256535

[15] Brandt. 2020. ‘Migrant, refugee and internally displaced children at the centre of COVID-19 response and recovery’, The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). https://www.unicef.org/eap/stories/migrant-refugee-and-internally-displaced-children-centre-covid-19-response-and-recovery

[16] eLearning Africa. 2020. The Effect of Covid-19 on Education in Africa and its Implications for the Use of Technology. https://www.elearning-africa.com/ressources/pdfs/surveys/The_effect_of_Covid-19_on_Education_in_Africa.pdf

[17] Fry & Lei. 2020. Girls’ Education and Covid-19, Malala Fund. https://downloads.ctfassets.net/0oan5gk9rgbh/6TMYLYAcUpjhQpXLDgmdIa/3e1c12d8d827985ef2b4e815a3a6da1f/COVID19_GirlsEducation_corrected_071420.pdf

[18] Human Rights Watch. 2020. Impact of Covid-19 on Children’s Education in Africa. Submission to The African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. 35th Ordinary Session. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2020/08/Discussion%20Paper%20-%20Covid%20for%20ACERWC.pdf

[19] Adriaamse, June 4 2020. ‘School closures factor in rape of Ethiopian girls during Covid-19 lockdown’, Independent Online. https://www.iol.co.za/news/africa/school-closures-factor-in-rape-of-ethiopian-girls-during-covid-19-lockdown-48970387

[20] UNESCO. 2015. Learning metrics task force: Recommendations for universal learning. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/learning-metrics-task-force-recommendations-universal-learning-brochure-education-2013-en_0.pdf

[21] Bruns, B., Mingar, A., &Rakotomalala, R. 2003. Achieving universal primary education by 2015: A chance for every child. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

[22] Evans, D., Kremer, M., & Ngatia, M. 2008. The impact of distributing school uniforms on children’s education in Kenya. Poverty Action Lab. https://www.povertyactionlab.org/evaluation/impact-distributing-school-uniforms-childrens-education-kenya

[23] Montgomery, P., Ryus, C.R., Dolan, C.S., Dopson, S., & Scott, L.M. 2012. Sanitary pad interventions for girls’ education in Ghana: A pilot study. Plos One 7(1).

[24] United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2019. Global education monitoring report. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265866

[25] Centre for Child Law and Others v Minister of Basic Education and Others (2840/2017) [2019] ZAECGHC 126; [2020] 1 All SA 711 (ECG); 2020 (3) SA 141 (ECG) (12 December 2019). http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZAECGHC/2019/126.html

[26] https://www.groundup.org.za/article/major-court-victory-eastern-cape-learners/

Categories:

Tags: