Refugee Status? Included in or Excluded from Refugee Protection?

SIHMA’s new research paper series is coming out this December 2020 entitled the Advocates’ Migration Brief and addresses recent judicial decisions relating to people on the move. The first paper in the series convers an aspect of international and domestic refugee law being exclusion from refugee status. In the refugee status determination process, it is important to establish whether a person falls within the definition of a refugee to receive protection from the host state. Some individuals though might meet the requirements of one or more definition but may nevertheless be excluded from protection because they may be considered to not be deserving of or in need of protection. The first paper in the series is entitled Exclusions, Unintended Consequences, and Gavrić v Refugee Status Determination Officer and explores the application of exclusion provisions in the South African context.

Article 1F of the 1951 UN Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (the 1951 Convention) and similarly Article I(5) of the 1969 Organisation of African Unity Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (the 1969 Convention) each address those who are excluded from refugee protection. These conventions have been domesticated into legislation in a number of African countries. In South Africa section 4 of the Refugees Act [1] pertains to those who are excluded from refugee protection.

In terms of section 3 of the South African Refugees Act [1], a refugee is defined as a person who owing to a well-founded fear of persecution under one of the listed grounds (eg political opinion) fled their country and is, owing to such fear, unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin, or someone who flees war or serious disturbances to public order in part of or the whole of one’s home country, or is a spouse or dependent of a person contemplated in the first two definitions [1]. However, once a migrant falls within one of the definitions they may still not be entitled to refugee protection if they fall within one of the categories of persons that are excluded from protection in terms of section 4 (1) As the impact of excluding a person from protection may have very serious consequences extensive safeguards are in place in terms of the Refugees Act, the South African constitution and other applicable laws [2]. In terms of the Refugees Act a decision-maker may lawfully reject or bar someone who would normally qualify for refugee status in situations whereby [1]:

- he or she has committed a crime against peace, a war crime, or a crime against humanity; or

- he or she has committed a crime which is not of a political nature and which, if committed in South Africa, would be punishable by imprisonment; or

- he or she has been guilty of acts contrary to the objects and principles of the United Nations or the African Union; or

- he or she enjoys the protection of any other country in which they have taken residence.

These exclusion provisions are of an exceptional nature owing to the potentially serious consequences of exclusion from refugee status for the individual concerned [2]. They should be applied scrupulously and restrictively. Additionally the third provision is further qualified in section 4 that ‘no exercise of a human right recognised under international law may be regarded as being contrary to the objects and principles of the United Nations or the African Union’ [1].

Internationally and domestically exclusion provisions have been analysed by courts to establish the appropriate application of the provisions. The provisions have been addressed in South Africa in case of a former Rwandan general in the Consortium for Refugees and Migrants in South Africa v the President of the Republic case [3] and in the case of national from the former Republic of Yugoslavia who was excluded from refugee protection giving rise to the challenging of this decision at the High Court and then at the Constitutional Court in the case of Gavrić v Refugee Status Determination Officer [4]. The case brought a constitutional challenge to the application section 4(1)(b) of the Act [1].

The case concerned an application for refugee status made by Dobrosav Gavrić, a Serbian national who used to work as a police officer in the former Republic of Yugoslavia[4]. Gavrić entered the country irregularly in 2007 and the authorities only became aware of his real identity when he became the victim of a shooting incident in 2011 [5]. He was consequently charged and arrested for possession of drugs and for fraud for using falsified documents [5]. In 2012, Gavrić applied for refugee status on the basis that he feared being killed, for the acts he committed as a police officer in the former Republic of Yugoslavia, if he was to be returned to Serbia (his country of origin)(4). The Refugee Status Determination Officer rejected his application on the basis of section 4[1][b] (1), owing to Gavrić’s prior murder conviction [5].

Unhappy with this decision, Gavrić approached the High Court to contest the decision and contest the constitutionality of the relevant provisions of the Refugees Act [5]. Following the dismissal of the application by the High Court, Gavrić then approached the Constitutional Court. The first edition of the Advocates Migration Brief working paper series analyses the arguments made to and the finding of the Constitutional Court in this case and the impact it and other cases have on the application of exclusion provisions in South Africa. The issues addressed by the courts in this regard are of great importance to asylum seekers and refugees and impacts their applications for refugee status and their right to administrative justice. It is crucial that South Africa and other African Countries have the capacity and suitable mechanisms in place to protect genuine refugees and to identify the few claims that are undeserving of or not in need of protection.

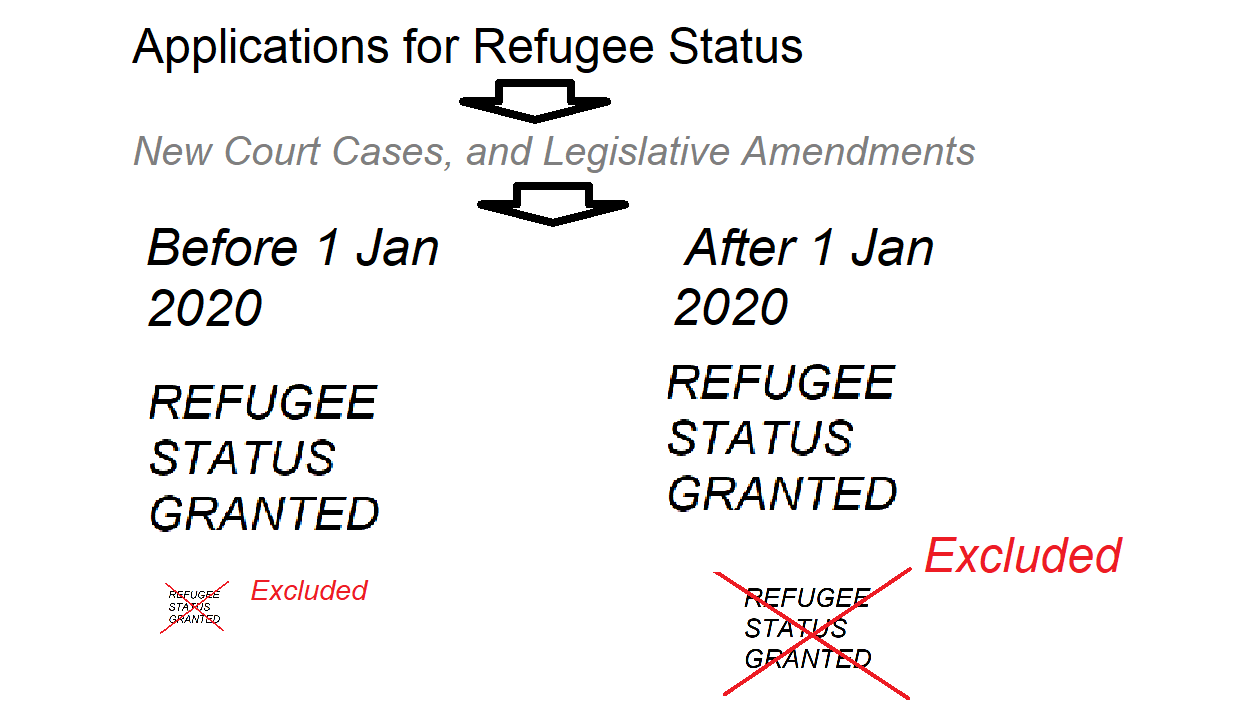

Furthermore in terms of exclusions, there have been a number of draft amendments to the Refugees Act including the extensive Refugee Amendment Act of 2017 which although signed into law in December 2017 only came into force on 1 January 2020 upon the promulgation of regulations relating to the Act. One amendment was the amendment of Section 4 of the Refugees Act which added additional categories of people that are excluded from protection because they are considered to be undeserving of or not in need of protection. The additional provisions and additions to existing provisions [6] have been underlined below:

Refugee Status Determination Officer has reason to believe that he or she—

(a) has committed a crime against peace, a crime involving torture, as defined in the Prevention and Combating of Torture of Persons Act, 2013 (Act No. 13 of 2013), a war crime or a crime against humanity…; or

(b) has committed a crime outside the Republic, which is not of a political nature and which, if committed in the Republic, would be punishable by imprisonment without the option of a fine; or

(c) has been guilty of acts contrary to the objects and principles of the United Nations… or the… African Union; or

(d) enjoys the protection of any other country in which he or she is a recognised refugee… resident or citizen…; or

(e) has committed a crime in the Republic, which is listed in Schedule 2 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1997 (Act No. 105 of 1997), or which is punishable by imprisonment without the option of a fine; or

(f) has committed an offence in relation to the fraudulent possession, acquisition or presentation of a South African identity card, passport, travel document, temporary residence visa or permanent residence permit; or

(g) is a fugitive from justice in another country where the rule of law is upheld by a recognised judiciary; or

(h) having entered the Republic, other than through a port of entry designated as such by the Minister in terms of section 9A of the Immigration Act, fails to satisfy a Refugee Status Determination Officer that there are compelling reasons for such entry; or

(i) has failed to report to the Refugee Reception Office within five days of entry into the Republic as contemplated in section 21, in the absence of compelling reasons, which may include hospitalisation, institutionalisation or any other compelling reason: Provided that this provision shall not apply to a person who, while being in the Republic on a valid visa, other than a visa issued in terms of section 23 of the Immigration Act, applies for asylum.

The amendments have added a further five categories of people that are excluded from protection [6]. These provisions substantially exceed the limited scope of exclusion provisions provide in the 1951 Refugee Convention and in the 1969 OAU Convention and have potentially very serious ramifications for people seeking asylum. The amendments distort what is envisioned as effective refugee protection and may have the effect of excluding and refouling genuine refugees based of not applying for asylum in time or for not entering the country through recognised channels or for fleeing political persecution and being labelled as a fugitive for ones country of origin or for obtaining irregular documentation. Not only are these amendments not in line with International Refugee Law but they are also contradictory to other South African legislation and case law such as the Ruta case [7] and are not likely to meet the constitutional muster.

For more on exclusions look out for the first edition of the Refugees Migration Brief coming soon.

In conclusion the courts have considered extensively refugee exclusion provisions with some consequences thereof that may not be what was originally intended. Additionally it appears that the new amendment and regulations relating to exclusions are significantly reducing the protection space available to asylum seekers and adding to the vulnerability of constitutionally recognised vulnerable demographic [8]. Civil society and refugee assistance organizations have expressed grave concern at the new law as it places asylum seekers and refugees in an even more vulnerable situation [9].

Read the first Briefing of the series here:

https://sihma.org.za/advocates-migration-brief/unintended-consequences-for-exclusions

James Chapman and Christine Lalor

SIHMA SIHMA

Project Manager Research and Communication Intern

Resources:

- Refugees Act 130 of 1998, accessed at: http://www.saflii.org/za/legis/consol_act/ra199899/#:~:text=To%20give%20effect%20within%20the,for%20the%20rights%20and%20obligations

- Chapter 6, Khan & Schreier, 2014, Refugee Law in South Africa, 2014.

- Consortium For Refugees and Migrants in South Africa v President of the Republic of South Africa and Others (30123/2011) [2014] ZAGPPHC 753 (26 September 2014) accessed at: http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZAGPPHC/2014/753.html

- Gavrić v Refugee Status Determination Officer, Cape Town and Others, (CCT217/16) [2018] ZACC 38; 2019 (1) SA 21 (CC); 2019 (1) BCLR 1 (CC) (28 September 2018), accessed at: http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2018/38.html

- Ampofo-Anti, O. 2018. Concourt agrees: people guilty of serious crimes will not qualify for refugee status. Ground Up. Accessed at: https://www.groundup.org.za/article/constitutional-court-agrees-persons-guilty-serious-crimes-will-not-qualify-refugee-status/

- Section 4 as Amended by Refugee Amendment Act 11 of 2017, accessed at: http://www.saflii.org/za/legis/num_act/raa201711o2017g41343231.pdf

- Ruta v Minister of Home Affairs (CCT02/18) [2018] ZACC 52; 2019 (3) BCLR 383 (CC); 2019 (2) SA 329 (CC), accessed at: http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2018/52.html

- Union of Refugee Women and Others v Director, Private Security Industry Regulatory Authority and Others (CCT 39/06) [2006] ZACC 23; 2007 (4) BCLR 339 (CC) ; (2007) 28 ILJ 537 (CC); 2007 (4) SA 395 (CC) (12 December 2006), accessed at: http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2006/23.html

- Ground up article entitled: SA’s new refugee regulations could have been drafted by Trump, says activist, By Tania Broughton. Accessed at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-01-17-sas-new-refugee-regulations-could-have-been-drafted-by-trump-says-activist/

Also see Scalabrini. 2020. The Refugee Amendment Act. Scalabrini Centre of Cape Town accessed at: https://scalabrini.org.za/news/refugee-amendment-act/

Categories:

Tags: