Youth Day 2021

Sport: A valuable tool for social inclusion amongst migrant youth in South Africa

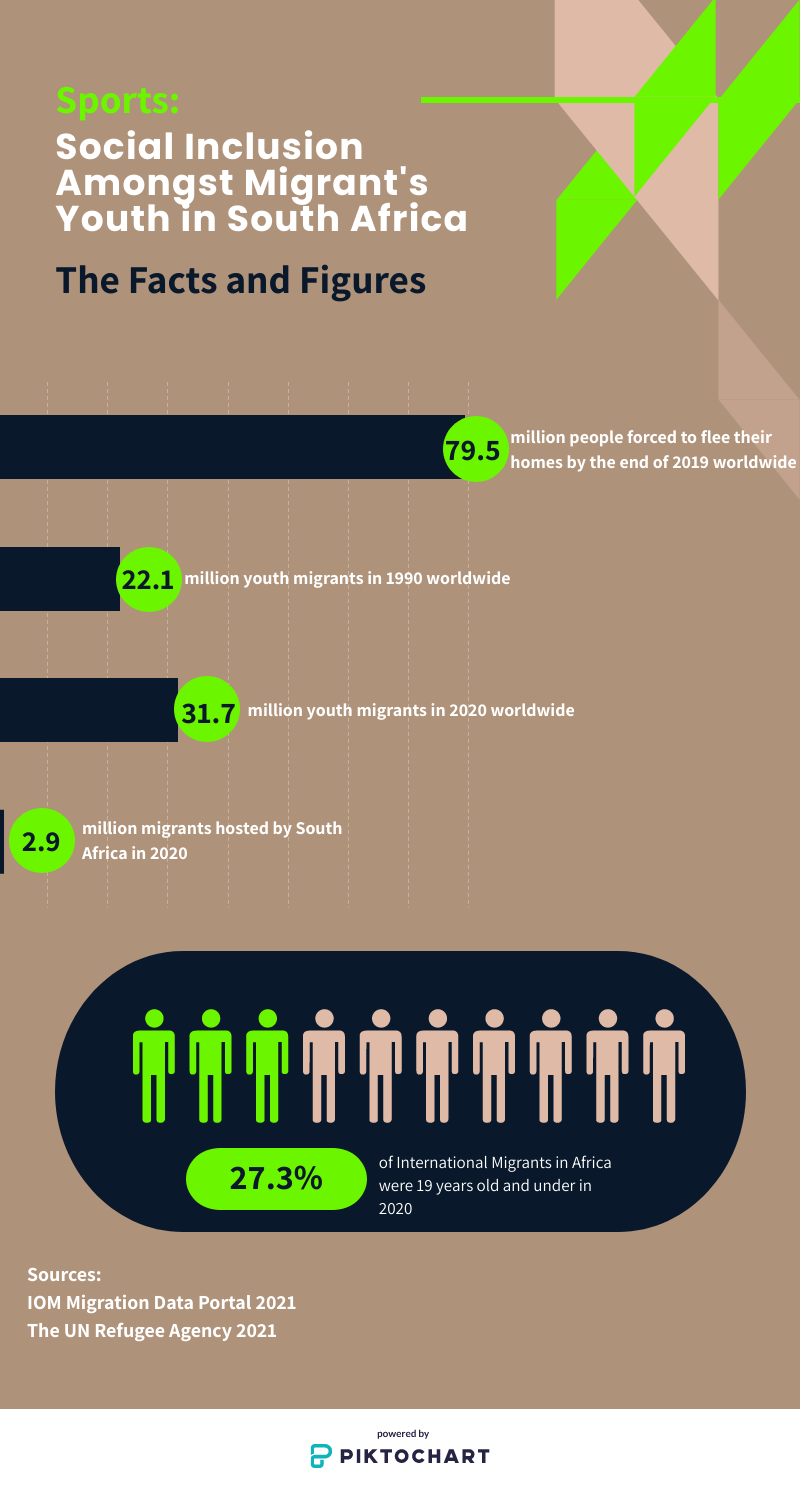

According to UNHCR [1], at least 79.5 million people had been forced to flee their homes by the end of 2019 worldwide. By 2020, South Africa hosted 2,9 million migrants [6]. This equals approximately 4,8% of the total South African population [6]. At mid-year 2020, 27.3 % of International Migrants in Africa were 19 years old and under and young migrants aged 15 to 25 constituted 16.2% of International Migrants [5]. In South Africa, these numbers were respectively 11.1% and 13.8% [6]. The number of young migrants aged 15 to 24 has been rising from 22.1 million in 1990 to 31.7 million in 2020 globally [14]. These trends indicate the growing number of youths who live in countries other than that of their birth, and there is therefore a need to develop strategies through which to integrate these migrants within their newfound spaces.

Social inclusion and exclusion are terms that are often used together with the one explaining the other. According to Peace, the terms social inclusion and exclusion are derived from the terms poverty, deprivation, and marginalization [8]. Percy-Smith states that the term “social exclusion” was first adopted by the New Labour Government of the United Kingdom, which led to the creation of a social exclusion unit in 1977, whose job was to take care of people on benefit who were unable to work [9]. Building on the British concept of social exclusion, Ward argues that excluding others from participating in the mainstream economy is a form of social control which limits or seeks to limit people's choices about how and where to live their lives [15]. Social inclusion is seen as a process where efforts are made to ensure equal opportunities for all, regardless of their background, so that they can achieve their full potentials in life.

Spoonley et al. contend that inclusion involves equality of opportunities and outcomes with regards to labour market participation and income, access to education and training, social benefits, health services, and housing [11]. The above definition emphasizes equal access to all community members concerning services rendered by the state. According to Mkhwanzi, inclusion is a multidimensional process aimed at creating conditions that enable the full and active participation of every member of the society in all aspects of life, including civic, social, economic, and political activities, as well as participation in the decision-making process [7]. Looking at the definition above, it entails a utopian society where everybody is expecting to participate, but what is so crucial in the definition is the fact that it views social inclusion as a process and it upholds diversification of society as its main pillar. The definition embraces the whole notion of a society that appreciates each other the way they are.

Sport remains one of the viable options through which social inclusion can be achieved, as sport is a universal language that can break down cultural and linguistic barriers. Its prominence in the media -which dedicate considerably more coverage to sport than to politics and economics - demonstrates its relevance. According to Jarvie and Maguire, sport and leisure activities form an integral part of social life in all communities and are intricately linked to society and politics [3]. Kim mentions four key aspects of sport that can be useful tools in social inclusion and peace-building processes between parties of different cultural backgrounds [4]. These are sport as so-called non-verbal means of communication; sport programmes as occasions of collective experience and direct physical contact; sport as a medium which transcends division of class; and sport as an instrument of culture. United Nations agencies in the spirit of the New Millennium Development goals and globalization view sport as an instrument for peace-building, conflict prevention, and development. Sport can greatly help in the psychological rehabilitation of refugees and asylum seekers - particularly unaccompanied children and teenagers. Sport build bridges amongst people of different origins and can also be used to help post-war trauma treatment [10].

Research conducted with 30 organizations working in educational and community sports in the UK established that sport, leisure, and cultural activities were beginning to emerge as potentially powerful tools in helping to shape social inclusion and cohesion in respect to asylum seekers and refugees [13]. They postulated that sport can be a useful tool for initiating dialogue, thus decreasing tension between communities, and establishing a channel of communication between the police authority and communities, which in turn may contribute to crime prevention within communities. In 2019, more than 80 entities pledged to support refugees and host communities through sports to assist and promote a new global framework for refugee response, drawing actors from the private sector, faith-based organizations, cities, academic institutions, and the world of sport amongst others to engage [13].

The most popular sports in South Africa include cricket, rugby, and soccer. Other sports which enjoy a particular good amount of following, include athletics, basketball, boxing, golf, netball, swimming, and tennis. During the dawn of democracy in South Africa, sport was used as a tool to push forward the reconciliation agenda between whites and blacks in the country by the newly elected democratic president Nelson Mandela, during the rugby world cup finals in 1995. By wearing a Springbok Rugby shirt of a white player - Francois Piennar, and a baseball cap at the pre-game ceremony, Hargreaves felt that the president brilliantly used the springbok emblem and transformed it from a symbol of white superiority to one of national unity [2]. If sport was used as an instrument to create a sense of unity amongst South Africa, in the same light, South African youths can use sport as they celebrate youth month to change the negative narrative constructed within South Africa against migrants, and most especially migrants from Africa. Thus, sport can be a powerful tool for inclusion, cohesion, health, relief, and human connection.

James Chapman and Muluh Momasoh

SIHMA SIHMA

Project Manager Junior Researcher

INTEREST IN WRITING SOMETHING FOR SIHMA?

If you are interested in contributing the SIHMA Blog on the Move please contact us at: https://www.sihma.org.za/contact or if you are interested writing an article to be reviewed and published in the African Human Mobility Review, please follow this link on making a submission: https://www.sihma.org.za/submit-an-article

REFERENCE LIST

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2021. Sport Partners. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjCleWWuI3xAhXbgVwKHbowCX8QFjAAegQIDRAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.unhcr.org%2Fsport-partnerships.html&usg=AOvVaw3hw5lqVHko0lIjqzz9d1sT

- Hargreaves, J. (2000). Heroines of sport: Routedge

- Jarvie, G. & Maguire, J. (1994) Sport and Leisure in Social Thought. London and New York: Routledge.

- Kim, M. (2008). Sport as Opportunity for Community Development and Peace Building in South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwj894fa_o7xAhUBExoKHdViD04QFjAOegQIExAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sportanddev.org%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fdownloads%2F64__sport_as_opportunity_for_community_development_and_peace_building_in_south_africa.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2ceyiL8EZs5MfA-M0DSnPi

- Migration Data Portal. (2021, 20 January). International Data. Retrieved from: https://migrationdataportal.org/international-data?i=stock_young_perc&t=2020&m=1&rm49=2

- Migration Data Portal. (2021, 20 January). Migration data, South Africa. Retrieved from: https://migrationdataportal.org/data?cm49=710&%3Bfocus=profile&i=stock_abs_&t=2020

- Mkhwanazi, M. (1993). “The migration Labour, System in Swaziland”. In: UNFPA Issues in Demography of Swaziland. Department of statistics and demography, University of Swaziland. PP 68-196.

- Peace, R. (2001). Social exclusion: A Concept in need of definition? Social Policy, Vol. 16: 17-36.

- Percy-Smith, J. (Ed). (2000). Policy response to Social exclusion. Towards Inclusion? Buckingham, Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Shcwenzer, A. (2017). Sports for refugees: Challenges for instructors and their support needs. Camino – Werkstatt für Fortbildung, Praxisbegleitung und Forschung im sozialen Bereich gGmbH. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjCleWWuI3xAhXbgVwKHbowCX8QFjAJegQIGRAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fsportinclusion.net%2Ffileadmin%2Fmediapool%2Fpdf%2Fspin%2F2017_SWR-Camino_Sports-for-refugees_Challenges-for-instructors-and-their-needs.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3pq6UO1IRJKEdJJTqzvzsX

- Spoonley et al, (2005). “Social cohesion: a policy and indicator framework for assessing immigrants and host outcomes” Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, Vol. 24: 85-110.

- Statista, 2021. South Africa: International migrants by gender 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjIvpD92Y3xAhVQhVwKHQhyCyoQFjABegQIBBAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.statista.com%2Fstatistics%2F1238536%2Fstock-of-international-migrants-in-south-africa%2F&usg=AOvVaw0w0o8lMn10s9b0Bjxcm2nG

- Amara, M., Aquilina, D., Henry, I., & Taylor, M. (2004). Sport and multiculturalism: Institute of Sport and Leisure Policy. Loughborough University in partnership with PMP Consultants.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UN DESA). 2020. International Migrant Stock. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjEtL3-1orxAhXGVsAKHU4eBvMQFjAAegQIAxAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.un.org%2Fdevelopment%2Fdesa%2Fpd%2Fcontent%2Finternational-migrant-stock&usg=AOvVaw3gColYwfJvqMbRKoJF2BbZ

- Ward, N. (2009). Social exclusion, Social identity and social work: Analysing Social exclusion from a material discursive perspective. Social work Education. Vol 28 (3) 237-252

Categories:

Tags: