Considering Impact of COVID-19 on the Lives and Livelihoods of Congolese Female Asylum Seekers and Refugees

We had the pleasure of reading the latest edition of the African Human Mobility and in particular the second article entitled ‘COVID-19 and its Effects on the Lives and Livelihoods of Congolese Female Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the City of Cape Town’ [1].

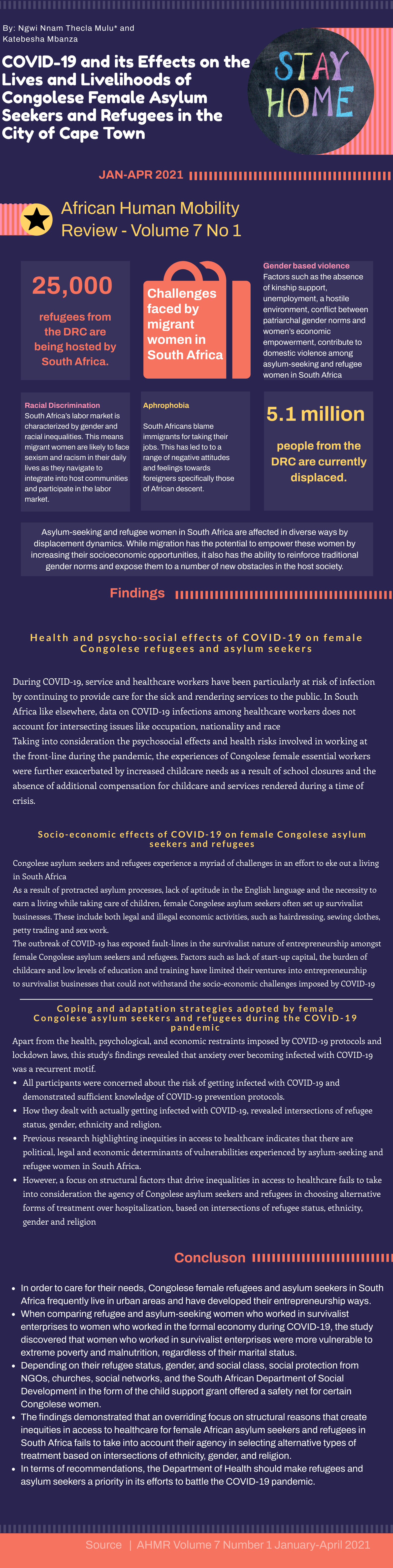

South Africa is a host of a minimum of 25,000 refugees from the war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo that has seen more than 5.1 million people displaced from the country [2]. Published in the 2021 African Human Mobility Review, Ngwi Nnam Thecla Mulu and Katebesha Mbanza from Rhodes University, South Africa, explore through a feminist perspective the socio-economic effects of COVID 19 on the lives and livelihood of female asylum seekers and refugees of Congolese descent in Cape Town, South Africa. They examined the growing feminization of migration into South Africa [3] and how it is a source of socio-economic empowerment to women as they are exposed to opportunities that help propel and position them to challenge gender norms based on patriarchy and religion [4] and allow them to forge new gender roles making them be agents of socio-cultural and economic change within society [5]. However, they are confronted with some challenges in their integration process through which they develop coping mechanisms.

The article is premised on the assumption that because of their migrant status, gender, race, and class, Congolese women survive at the intersection of multiple forms of vulnerability [1]. The article draws on the challenges confronting vulnerable migrants with a focus on Congolese migrant women in the informal sector in the South African economy during COVID 19. Emphasis is laid on how the informal sector is a major source of employment to the most vulnerable in society especially migrant women [1]. This sector was never categorized as a provider of essential services during level 3, 4, and 5 of the COVID 19 lockdown in South Africa that came with strict regulations thus limiting and constraining the source of livelihood of most migrants whose survival depended on this sector. These measures compounded their already existing vulnerabilities [6].

The authors argue that although the coping mechanisms of migrant women in South Africa are grounded in their possession of human, physical, social, cultural, economic, and political capital [7], asylum seekers and refugee women in South Africa are subjected to gender-based violence, Afrophobia and racial discrimination as they endeavour to integrate into the host community and the labour market [8]. However, asylum seekers and refugee women from the war-torn zone of the Democratic Republic of Congo who do not possess this capital develop alternative survival mechanisms within the informal economy with precarious work, for example, ‘as self-employed hairdressers, petty traders, tailors, sex workers, domestic workers and seasonal farm workers [9].

The study through an intersectional lens (gender and socio-economic status) reveals the extreme vulnerability to poverty and malnutrition of female Congolese refugees and asylum seekers residing in the urban areas in Cape Town, South Africa who rely on their informal businesses as a source of livelihood for their family in contrast with those employed in the formal sector who are much better off [1]. The study also zooms into the relevance of social protection provided by NGOs, churches, social networks, and the South Africa Department of Social Development in the form of the child support grant on how it acts as a safety net to these vulnerable women during COVID 19 [1]. However, they argue that access to healthcare remains a challenge to these women and that consequently some of them have resorted to alternative cultural practices of treatment during this period of COVID 19 [1]. The study recommends that because of their inaccessibility to health facilities, the government should prioritize refugees and asylum-seekers in their vaccination programs [1].

SOURCES

- https://sihma.org.za/journal/ahmr-volume-7-number-1-january-april-2021

- Schockaert et al., 2020: 33 see https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdz018

- Mbiyozo, 2018, Available at: https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/sar16.pdf

- Ojong, V.B. 2012. Career-driven migration: A new transnational mosaic for African women. Loyola Journal of Social Sciences, 26(2): 209-227.

- Pillinger, J. 2007. The feminisation of migration: Experiences and opportunities in Ireland. Dublin: Immigrant Council of Ireland. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjJhIO7iefwAhXISxUIHYLRC50QFjAAegQIAxAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Femn.ie%2Ffiles%2Fp_201211231144452007_Feminisation_of_Migration_ICI.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2sg4X-qR2n0nvf5G3PiCOV

- Mukumbang, F.C., Ambe, A.N. and Adebiyi, B.O. 2020. Unspoken inequality: How COVID-19 has exacerbated existing vulnerabilities of asylum seekers, refugees, and undocumented migrants in South Africa. International Journal of Equity in Health, 19:141. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjbgdzIgufwAhXMT8AKHS4FAUIQFjABegQIAhAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Frepository.uwc.ac.za%2Fhandle%2F10566%2F5574&usg=AOvVaw1LZSK-Qi8ZL29JC4cHcFSf

- Ncube, A. 2017. The socio-economic coping and adaption mechanisms employed by African migrant women in South Africa. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of the Free State, South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjg2e6vg-fwAhWlQxUIHZprCfUQFjACegQICxAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Fscholar.ufs.ac.za%3A8080%2Fbitstream%2Fhandle%2F11660%2F7732%2FNcubeA.pdf%3Fsequence%3D1%26isAllowed%3Dy&usg=AOvVaw1MJRDMNfiYTQEn_09odPTp

- Ramparsad, N. 2020. Why is COVID-19 different to other pandemics? Assessing the gendered impact of COVID-19 on poor black women in South Africa. African Journal of Public Sector Development Governance, 3(1):132-143. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjYyZrqhefwAhVdShUIHf-vBIcQFjAJegQIDBAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fjournals.co.za%2Fdoi%2Fabs%2F10.10520%2Fejc-ajpsdg-v3-n1-a7&usg=AOvVaw39ulOWbt87gidRQ3WzCdgF

- Halkias, D., and Anast, J. 2009. Female immigrant entrepreneurship in South Africa post 1994: Introduction – a brief review of the literature. African Journal of Business and Economic Research, 4: 25-33.

Categories:

Tags: