Historical Background

Historical Background

Zambia is an origin, transit, and destination country for migrants. The country’s complex and dynamic migration patterns yield mixed migration flows. Historically, migration has been interwoven into the socio-economic fabric of Zambian society. The discovery of copper in the Zambian Copperbelt in the 1920s and 1930s saw an unprecedented wave of both internal and international migration in Zambia. The mines attracted large foreign-based companies, and their exploration required a large labour force that drew labourers from all over the territory and beyond. However, with the fall in the price of copper and the subsequent economic recession experienced by the country, many Zambians are now relocating to rural areas to mitigate the high cost of urban living (Girard & Chapoto, 2017).

Zambia also has a long history of providing international protection and assistance to refugees, dating back to the 1940s when the first wave of refugees arrived in the country from Poland (Tembo & Lingelbach, 2021). Currently, refugees in Zambia predominantly come from African countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Burundi, Rwanda, and Somalia. Because of its centrality in southern Africa and its relative political stability, Zambia also attracts migrants from other parts of Africa who wish to transit to certain African countries, especially to South Africa as it is considered one of the most advanced countries on the continent.

Despite the political stability that Zambia enjoys, there are a significant number of internally displaced persons in the country. Cases of both internal and cross-border human trafficking are increasing at an unprecedented rate, fuelled mainly by socio-economic hardship in the rural areas.

Migration Policies

Migration Policies

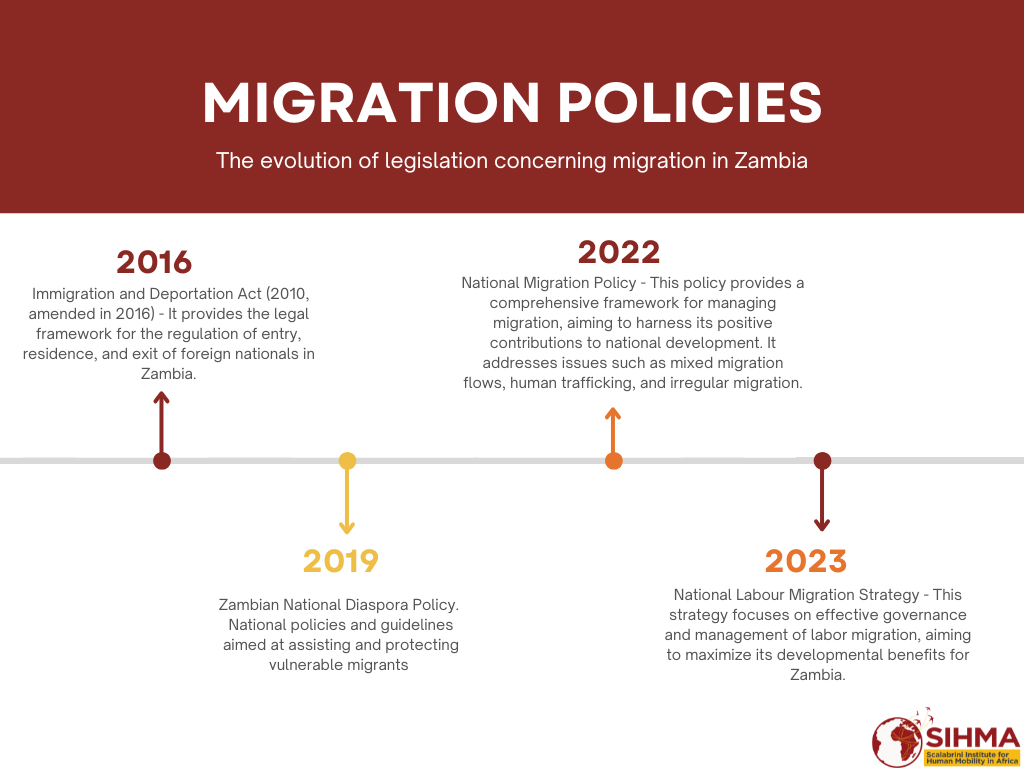

Several legal frameworks shape the migration landscape in Zambia. This includes the 2016 Constitution of Zambia.

· Constitution of Zambia, 2026, Article 39: This article sets up roles for dual citizenship.

· Vision 2030: This long-term plan focuses on human rights irrespective of status and emphasises the peaceful coexistence of migrants and nationals to promote social cohesion and tolerance.

· The Seventh National Development Plan 2017-2021: This plan seeks to enhance human development, among others.

· The Zambian National Diaspora Policy (2019): This policy seeks to integrate Zambian diaspora into the development agenda of the country.

· The National Protection Policy: This policy seeks to equip officials dealing with vulnerable migrants with the necessary skills to provide services that will respond to the protection needs of such migrants.

· The National Policy of 2007: This policy covers human trafficking and seeks to eradicate all forms of human trafficking while providing adequate support and protection to trafficked victims.

· Guidelines for Protection Assistance to Vulnerable Migrants in Zambia: These guidelines are aimed at effectively responding to the protection needs of vulnerable migrants in Zambia (IOM, 2019).

Timeline of Migration Policies in Zambia. Source: SIHMA

Zambia is also a party to a limited number of international instruments that relate to refugees and migrants. These include the Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugee Convention), the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), the Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, ILO Conventions on minimum age for employment, forced labour, and worst forms of child labour, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the UN Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), the International Convention on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and its first Optional Protocol, the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (Palermo Protocol), the underlying UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, and the Migrant Smuggling Protocol of 24 April 2005.

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

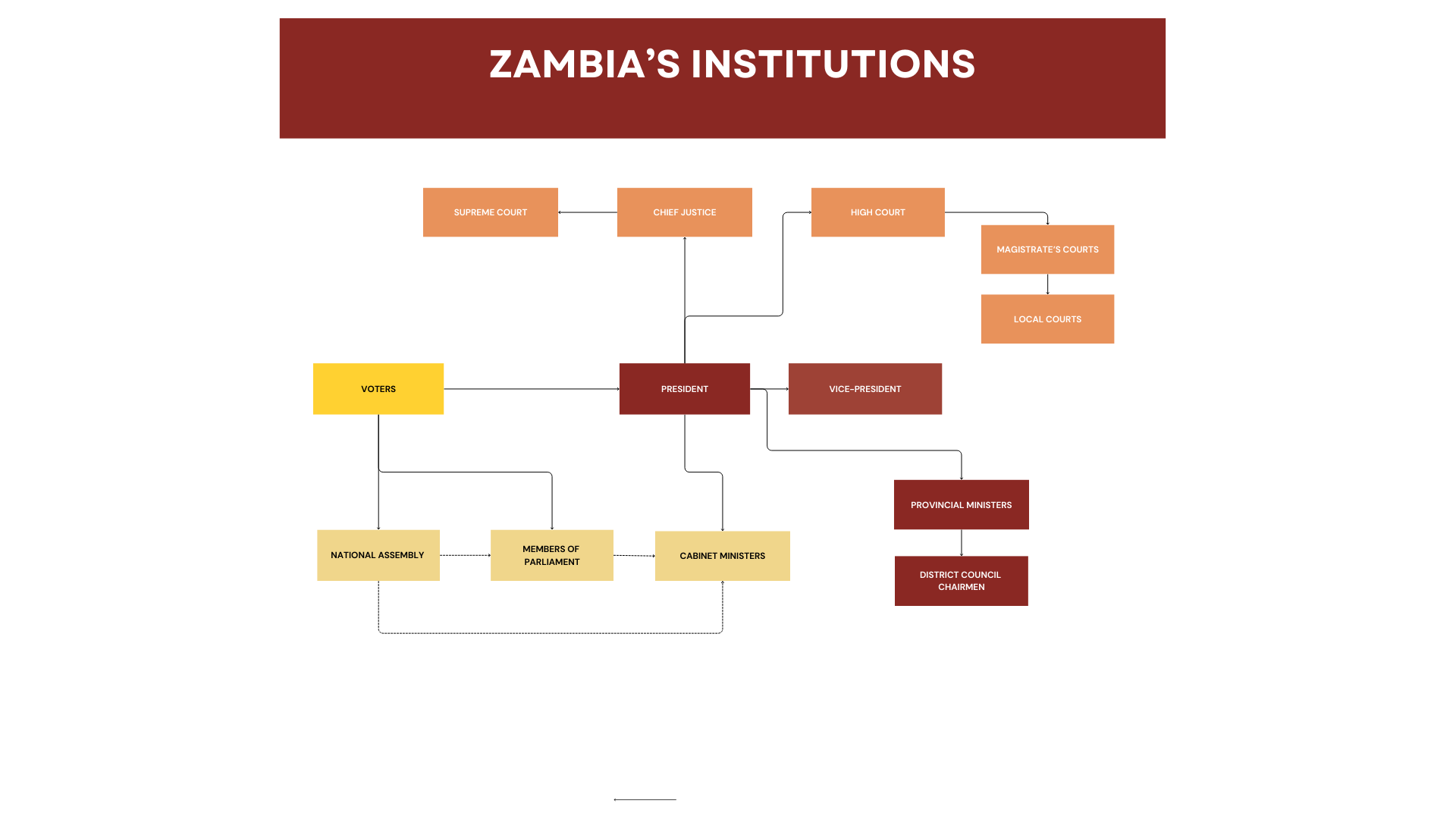

The main government institution responsible for migration-related issues in Zambia is the Department of Immigration – an arm of the Ministry of Home Affairs that regulates entry, exit, and stay in Zambia. The department has its headquarters in Lusaka with regional offices in all ten provinces in Zambia. Other ministries that work closely with the Department of Immigration to ensure the effective and efficient provision of services include the Ministry of Community Development and Social Services which provides social assistance, protection, and promotional services, and promotes an alternative to detention, especially for migrant children.

Zambia's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

The Ministry of Gender is mandated to promote gender equality to all, including developing gender policies that respond to the circumstances of migrant men and women. The Central Statistical Office collects migration-related data to inform the development of migration-related policies. The Disaster Management and Mitigation Unit (DMMU) seeks to, inter alia, put in place effective and efficient measures to manage the displacement of people caused by disaster outbreaks.

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

Internal migration in Zambia has been very dynamic. The discovery of copper in Zambia saw an increase in the rate of urbanisation informed by the movement of people from rural areas to urban areas to feed the growing demand for mine workers. Between 1963 and 1980, as a percentage of the total population, the rural-urban migration increased from 20.5% to 39.9% respectively in all urban areas (Ogura, 1991). According to the IOM (2019), the urban population rate as a percentage of the country’s population between 1990 and 2010 stood at 38% and 39.9%. This indicates a stable increase in internal movement in Zambia from 1963 to 2010. The movement can either be from rural to urban areas or from urban to urban areas.

The national census conducted in 2010 showed that 16.8% of people in Zambia were counted in districts other than those in which they were born (IOM, 2019). These statistics indicate that there is an internal movement of citizens across various administrative jurisdictions in the country. People who have migrated from one urban area to another constituted the biggest category of internal migration in Zambia at 38.7% (ibid). Rural-to-urban migration increased from 14.9% in 2010 to 20.7 % in 2015. The main reasons for internal migration were employment transfer of the breadwinner which was around 19.9% as well as the decision to settle (17.7%) (ibid). However, it is important to note that the economic recession in Zambia and the fall in the price of copper reduced the country’s growth rate by 50% which harmed the economy, forcing people to move back to rural areas as a survival strategy (African Forum and Network on Debt and Development, 2016).

Currently, urbanisation rate in Zambia is increasing. It currently stands at 40%, with an estimated 70% living in informal peri-urban settlements characterised by social, economic, and environmental deficiencies (UN-Habitat, 2022). In Zambia, the search for economic opportunities and the desire to make a livelihood constitute the pull force in the country’s internal migration landscape. The back-and-forth movement of migrants in the country is driven by the availability of opportunities or lack thereof in urban and rural areas.

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

Except for the mass forced displacement in the 1950s that saw approximately 57,000 Tonga-speaking people forced to move away from their usual places of residence to pave way for the construction of the Kariba man-made lake (The New Humanitarian, 2008), internal displacement in Zambia has largely been influenced by natural disasters such as storms and floods. Although conflict/violence displacements are minimal, their impact still hurts affected communities. Also, the commercialisation of agriculture and the government’s poor efforts to protect small-scale farmers have aggravated displacements. For example, in the district of Serenje, dozens of residents were forcefully displaced to make way for commercial farmers (Human Rights Watch, 2017).

The impact of disaster-related displacement is extensive compared to conflict/violence displacements. For example, between 2008 and 2023, there were 117,000 disaster-related displacements in Zambia (IDMC, 2024). In 2020, floods displaced 810 people in the central province of Mumbwa (ibid). In March and April 2024, flash floods displaced 4,100 people in Luapula province, 500 people in the eastern province of Mambwe, and 560 people in the eastern province of Lumezi (ibid). In 2021, storms displaced 53 people in the central province of Kapiri Mposhi while floods displaced 1,300 people in the central province of Mumbwa and Shakumbila (IDMC, 2021). More recently, in 2024, between 19 October and 11 December, the Displacement Tracking Matrix in Zambia identified 140,261 internally displaced persons (IOM, 2024). Disaster-related displacements leave a trail of devastation in the country including loss of lives, loss of livelihoods, and damage to property and infrastructure.

Immigration

Immigration

Stable and growing economies are some of the pull factors for investment and economic growth. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2006), the economy of Zambia experienced robust growth with a 4.5% average growth rate per year in 2000. The economic prosperity of the country was a pull force for international migrants. According to UN DESA (2025), the immigration stock in Zambia stood at 321,167 in 2000, its highest in more than two decades (2000 – 2024). This was followed by a period of decline: the immigrant population stock stood at 252,900 in 2005, at 150,000 in 2010, and at 132,100 in 2015. In 2020, it stood at 188,000.

The declining immigrant population stock can be attributed to factors such as political instability and the declining economy. According to the IOM (2019), drawing from the 2010 census data, an estimated 43,867 immigrants lived in Zambia, with the top origin countries being the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Zimbabwe, India, and Rwanda. With the recovery of the mining, services, and manufacturing sectors, the economy is projected to grow at a 4.5% rate in 2024 and 2025 (African Development Bank Group, 2024), attracting international migrants. According to UN DESA (2025), the immigrant population stock grew to 249,200 in 2024.

Female/Gender Migration

There are no recent statistics on the number of female immigrants in Zambia. However, according to the IOM (2019), based on the 2010 census data, there were an estimated 20,617 female immigrants in Zambia, constituting 47% of the immigrant population. Because Zambia is a member of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) aimed at establishing a free trade zone among its members within the region, women in particular are making good use of the window of opportunity and trade across international borders. For example, according to the United Nations (2022), more than 70% of informal cross-border traders in Zambia are women.

Children

Children

Partly because of the absence of a centralised aggregate database, there are no reliable statistics on the number of child migrants in Zambia. Child migration in Zambia is characterised by mixed movement that includes unaccompanied and separated minors, smuggled migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and victims of human trafficking. As services are not geared towards the protection of migrant children, there are inadequate shelters. This results in unaccompanied migrant children sometimes being placed in detention alongside adults and sometimes mixed with criminals. According to the UNHCR (2016), 49 children were detained in 2013 and 48 in 2014, and the number more than halved to 18 children in 2015. One of the reasons for the decline in child detention in Zambia is child migrants making themselves invisible to law enforcement officials, including the police (SIHMA, 2023). Although it increases their vulnerability, it takes them off the radar of law enforcement officials and their potential arrest (ibid).

Other policy frameworks that seek to protect the rights of migrant children in Zambia through the provision of quality services include the Guidelines for Best Interest Determination for Vulnerable Child Migrants.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

In line with its commitments under the UNHRC-supported Global Compact on Refugees (GCR) and the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF), refugees and asylum seekers in Zambia are protected in terms of the Refugees Act of 2017. Refugee-related affairs are specifically managed by the Office of the Commissioner of Refugees in the Ministry of Home Affairs. According to the UNHCR (2023), by September 2023, Zambia was hosting 92,042 people of concern, of which 68,670 were refugees, 5,935 were asylum seekers, and 17,437 were former refugees. They were located in three refugee settlements (Meheba, Mayukwaukwa, and Mantapala) while others were in the urban areas of Lusaka and Ndola, and the remainder were self-settled in 28 districts in five provinces (UNHCR, 2022a). By February 2022, approximately 46% were women and 47% were children (UNHCR, 2022b). People of concern in Zambia are primarily from the Democratic Republic of Congo (55,060), Burundi (8,659), Somalia (3,371), and Rwanda (873) (UNHCR, 2022a).

While there was a slight decline in the number of people of concern in Zambia in 2023 (92,042) compared to 2022 data (94,618), the number of refugees and asylum seekers increased slightly from 66,981 in 2022 to 68,670 in 2023 and 3,815 in 2022 to 55,060 in 2023 respectively (UNHCR, 2023). The decline in the number of people of concern was informed by a decline in the number of former refugees from 22,822 in 2022 to 17,437 in 2023 (ibid). In line with the GCR, CRRF, and the Refugees Act of 2017, refugees in Zambia have access to basic social services on the same level as Zambians while these legal instruments also ensure the socio-economic integration of refugees in the country (UNHCR & Republic of Zambia, 2019).

Emigration

Emigration

Copper is the main source of foreign earnings. The fall in copper prices in the 1970s adversely affected Zambia's economy and precipitated a new wave of emigration. The economic situation was compounded in the 1990s by the privatisation of parastatals and the liberalisation plans from 2000 to 2005 when Zambia tried to reach the Completion Point for the Highly Indebted Poor Countries initiative using a wage and employment freeze (SIHMA, 2020).

There are no reliable statistics on emigration from Zambia as the government focuses on those coming into the country and pays very little attention to those leaving the country. Between 2013 and 2017, international data sources indicated that a total of 278,355 emigrants had left the country for various destinations (IOM, 2019). The total estimated population of emigrants represented 1.6% of the 2018 projected Zambian population. The most popular destinations for emigrants from Zambia were South Africa, Malawi, Zimbabwe, the United Kingdom, the United States, Botswana, the United Republic of Tanzania, Namibia, Australia, and Mozambique (ibid). Apart from employment opportunities which are usually considered by the majority, migration for study purposes is another main reason people emigrate from Zambia. From 2013 to 2017, an estimated 13,921 students left Zambia to study outside the country, with the majority of them going to South Africa (17.9%) and Namibia (11.7%) (ibid).

Labour Migration/Brain Drain

Labour Migration/Brain Drain

Zimbabwe has a long history of labour migration. Besides being a sending and a transit country for labour migrants, Zimbabwe is also a receiver of migrant labour – especially from Malawi, Mozambique, and South Africa. According to IOM (2020), a labour migration report estimated that there were 78,000 migrant labour workers in Zimbabwe - constituting 37.7% of the total migrant population in Zimbabwe. In an attempt to protect migrant workers both in Zimbabwe and Zimbabweans living and working abroad, the government initiated the National Labour Migration Policy (NLMP) of Zimbabwe. Despite the progressive nature of the NLMP, Zimbabwe is yet to ratify the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention 97 on Migration for Labour and 143 on Migrant Workers Supplementary Provision.

Unauthorised Migration/Trafficking, Smuggling

Unauthorised Migration/Trafficking, Smuggling

Zambia is a source, transit, and destination country for trafficking, and internal and cross-border trafficking is gaining momentum in the country. Zambia is also a Tier 2 country, as the government is making significant efforts in some respects but does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking (US Department of State, 2023). Cases of both internal and cross-border human trafficking activities are increasing at an unprecedented rate in Zambia because of poverty, unemployment, and displacement (Borgen Project, 2023). Many people become victims of human trafficking when they attempt to escape from their socio-economic circumstances in rural areas.

The greatest percentage of trafficked citizens are those moving from rural to urban areas. Naivety regarding immigration procedures and the dangers of avoiding designated border post routes make migrants vulnerable to trafficking. These victims include stranded women, girls, and boys from remote parts of the country who are taken into prostitution and other transactional sexual behaviours, forced labour in agriculture, textile production, mining, construction, and small businesses such as bakeries, and forced begging (US Department of State, 2023). Also, migrant women are manipulated to lay false refugee claims in Zambia and are later coerced into prostitution (ibid). In 2022, the government initiated 42 trafficking investigations, nine prosecutions involving 17 defendants, continued four prosecutions from 2021, and obtained convictions for six traffickers in five cases (ibid). The low conviction rate can partly be ascribed to the government conflating migrant smuggling and human trafficking (ibid).

Remittances

Remittances

For the past ten years, the government of Zambia has increasingly recognised the positive contribution migration and diaspora engagement play in the development drive of the country. The remittance flow in Zambia has fluctuated significantly since 2003 when the first official data on remittances was captured. According to data provided by the World Bank (2008; 2016) and Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), as cited by Nyamazana (2022), remittance flow in Zambia increased from 2003 to 2008 and fluctuated from 2009 to 2019. For example, remittance flow increased from $36 million in 2003 to an estimated $135 million in 2020. Between 2003 and 2019, remittance flow in Zambia experienced a yearly uptick from 2003 ($36 million) to 2008 ($68 million) and started fluctuating from 2009 ($41 million) to 2019 ($98 million) (ibid). This is an acknowledgement of the role of the diaspora in the development of the country, as enshrined in the 2019 Diaspora Policy Document in Zambia. The policy seeks to promote, facilitate, and leverage remittances.

Returnees

Returnees

From 1983 to 1999, the state ran a programme for the voluntary return and integration of skilled Zambians who had emigrated: travel arrangements were facilitated and jobs in the public sector were offered to those willing to return. In 2005, the National Employment and Labour Market Policy aimed to implement return programmes for professionals while the Bonding System required students who had benefitted from public scholarships to work for the government for a period equivalent to their studies.

The emigration of qualified workers (teachers, doctors, and nurses) in the health care and education sector adversely affects the country. The limited investment in educational infrastructure to mitigate against the outflow of these professionals is creating an occupational gap in the country. The government is trying to respond by offering the Zambian diaspora the opportunity to return (even temporarily), buy land, participate in businesses, or invest in development projects. Currently, no data is available on voluntary returnees. However, the IOM (2019) stated that Zambia experienced a steady increase in involuntary returnees from 2013 (543) to 2016 (2,411) but a decline in 2017 (1,241).

The Diaspora Policy Document (2019) emphasises the need to promote permanent or temporary returns to Zambia, to build a cooperation network between Zambian professionals abroad and the home country to encourage the return of skills, and to create a database of available skills in the diaspora matched to local needs and available opportunities.

During the Covid-19 lockdowns, many Zambian nationals caught up in South Africa received assistance from the Zambia High Commissioner in South Africa, which facilitated the return of 106 Zambian nationals (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation Zambia, 2022). The department also facilitated the return of six Zambians and 30 resident permit holders to Zambia (ibid).

International and Civil Society Organizations

International and Civil Society Organizations

Several migration-related international organisations are working in Zambia:

• UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR): The UN Refugee Agency in Zambia supports the government’s efforts to provide protection and assistance to refugees and asylum seekers. These include safe and fair access to territory, asylum procedures and rights, inclusion in national services, self-reliance, and opportunities to earn a living and long-term measures such as integration into Zambia as the host country and possible resettlement in third countries.

• International Organization for Migration (IOM): IOM Zambia’s programmes focus on labour migration and development, diaspora engagement, countering human trafficking and migrant smuggling, border management, migration research, international migration law, and migrants’ rights, migration health and gender, disaster risk reduction, voluntary repatriation, and the resettlement of refugees.

• Women Refugees Community in Zambia (WRCZ): This organisation focuses on empowering women and combating discrimination against refugee women in Zambia.

African Forum and Network on Debt and Development. 2016. Impact of fluctuating commodity prices on government revenue in the SADC region: The Case of Copper for Zambia. Retrieved from: https://www.africaportal.org/documents/18345/IMPACTS_OF_FLUCTUATING_COMMODITY_PRICES_ZAMBIA_1.pdf

Borgen Project. 2023. Human trafficking in Zambia. Retrieved from: https://borgenproject.org/human-trafficking-in-zambia/

Girard, P. & Chapoto, A. 2017. Zambia: Internal migration at the core of territorial dynamics. In: Mercandalli, S. & Losch, B., eds. Rural Africa in motion: Dynamics and drivers of migration South of the Sahara. Rome: FAO and CIRAD. pp. 34-35. Retrieved from: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/586997/1/ID586997.pdf

Human Rights Watch. 2017. “Forced to Leave”: Commercial farming and displacement in Zambia. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/10/25/forced-leave/commercial-farming-and-displacement-zambia

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2024. Country profile: Zambia. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/zambia

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Study of unaccompanied migrant children in Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://scalabrini.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/International-organisation-for-migration-report.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. Migration in Zambia: A country profile 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.zambiaimmigration.gov.zm/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Zambia-Migration-Profile-2019.pdf

Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation Zambia. 2020. The Zambia Mission in South Africa facilitates the return of 106 Zambian nationals. Retrieved from: https://www.facebook.com/109795000664296/photos/a.113074413669688/141042654206197/?type=3

Nyamazana, M. 2022. Zambia national remittances study: Report. International Organization for Migration, Lusaka. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/country/Zambia/PUB2022-082-EL_Zambia_National_Remittances_Study_16Aug22_v04.pdf

Ogura, M. 1991. Rural-urban migration in Zambia and migrant ties to home villages. Developing Economies, 29(2):145-165. Retrieved from: https://www.ide.go.jp/library/English/Publish/Periodicals/De/pdf/91_02_03.pdf

Scalabrini Institute for Human Mobility in Africa (SIHMA). 2020. Zambia. Retrieved from: https://www.sihma.org.za/african-migration-statistics/country/zambia

Tembo, A. & Lingelbach, J. 2021. Africa is a Country | The forgotten history of migration to Africa. Retrieved from: https://africasacountry.com/2021/01/from-war-torn-europe-to-peaceful-africa

The New Humanitarian (TNH). 2008. Zambia: A new kind of internally displaced people. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-new-kind-internally-displaced-people

UN Habitat. 2022. Urbanization in Zambia. Retrieved from: https://unhabitat.org/zambia

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2016. Zambia: Global strategy beyond detention. Retrieved from: http://www.unhcr.org/57b5842c7.pdf

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022a. Zambia: Operational update. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-unhcr-operational-update-september-2022#

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022b. Zambia: UNHCR operational update. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/zambia/zambia-unhcr-operational-update-february-2022

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023. Zambia: Country overview. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/zmb#

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Nd. Migration profile: Zambia. Retrieved from: https://esa.un.org/miggmgprofiles/indicators/files/Zambia.pdf

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) & The Republic of Zambia. 2019. Implementing a comprehensive refugee response: The Zambia experience. Retrieved from: https://globalcompactrefugees.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/Zambia%20CRRF%20Best%20Practices%20Report_FINAL.PDF

United Nations. 2022. Zambia. Retrieved from: https://zambia.un.org/en/178936-innovation-helps-zambian-women-and-youth-bounce-back-cross-border-trade

US Department of State. 2021. Trafficking in person report: Zambia. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-trafficking-in-persons-report/zambia/

US Department of State. 2023. Trafficking in person report: Zambia. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/zambia/

World Bank. 2022. International migration stock, total: Zambia. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.TOTL?locations=ZM