Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and the African Union (AU)

The Regional Economic Communities (RECs) are regional groups of African states. The RECs have developed individually and separated from one another and have different roles and structures. Generally, the purpose of the RECs is to facilitate economic integration between members of the individual regions and through the African Economic Community (AEC), which was established under the Abuja Treaty of 1991. The 1980 Lagos Plan of Action for the Development of Africa and the Abuja Treaty proposed the creation of RECs as the basis for wider African integration, with a view of regional and eventual continental integration. The RECs are increasingly involved in coordinating African Union (AU) Member States’ interests on topics such as peace and security, development and governance.

The RECs are closely integrated with the AU’s work and serve as its building blocks. The relationship between the AU and the RECs is mandated by the Abuja Treaty and the African Union Constitutive Act and guided by the 2008 Protocol on Relations between the Regional Economic Communities and the African Union, as well as the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on Cooperation in the Area of Peace and Security between the AU, RECs and the Coordinating Mechanisms of the Regional Standby Brigades of Eastern and Northern Africa. The AU recognizes eight RECs:

- Arab Maghreb Union (AMU)

- Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA)

- Community of Sahel–Saharan States (CEN–SAD)

- East African Community (EAC)

- Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS)

- Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

- Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)

- Southern African Development Community (SADC)

In addition, the Eastern Africa Standby Force Coordination Mechanism (EASFCOM) and North African Regional Capability (NARC) have liaison offices at the AU. [Source: African Union, RECs]

History of the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU)

The Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), also known as the Union of the Arab Maghreb (UMA), is an economic and political partnership among five North African countries. Founded on February 17, 1989, in Marrakech, Morocco, the AMU was envisioned to foster regional unity and cooperation among nations with shared historical, cultural, and linguistic ties. The roots of the AMU trace back to ancient times, with North African nations historically linked by cultural and linguistic commonalities as well as trade routes traversed by the nomadic Berbers as early as 3000 B.C. Over centuries, these lands were ruled by a succession of foreign powers, including Phoenicians, Romans, Arabs, Ottoman Turks, and European colonial powers. This shared experience of external domination, especially by European colonial forces, fostered a common identity among the people of North Africa, which later fueled aspirations for unity and cooperation in the post-colonial era. [Source: AMU, History] The path toward formal collaboration among North African countries began in the late 1950s, soon after the region’s decolonization process started. Libya was the first North African country to gain independence in 1951, transitioning from Italian colonial rule to a United Nations-backed independence process. Morocco and Tunisia followed in 1956, emerging from French protectorates, while Mauritania became independent from France in 1960. Algeria, after a prolonged and brutal struggle, achieved independence from France in 1962. With newfound sovereignty, these countries turned their attention toward unification, holding the Maghreb Unity Congress in Tangier in 1958. However, national priorities and internal political challenges impeded any progress on the process. [Source: AMU, History]

In 1964, the first formal economic cooperative structure was established in Tunis, the "Conseil Permanent Consultatif du Maghreb" (CPCM), which sought to harmonize development and trade strategies among Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia. Despite the promising foundation, the CPCM struggled to deliver tangible results due to diverging national interests, particularly regarding the contentious issue of the Western Sahara. It was not until the late 1980s, with renewed diplomatic efforts and regional cooperation, that the AMU was formally established as a legal entity. The primary objectives of the AMU, as articulated in the Marrakech Treaty of 1989, reflect a vision for regional solidarity, economic integration, and shared prosperity. [Source: AMU, The Arab Maghreb Union] The key goals include:

- Strengthening Ties of Brotherhood: The AMU aims to reinforce the bonds of kinship and brotherhood between its member states and their peoples, leveraging their cultural and historical affinities as a foundation for unity.

- Fostering Economic and Social Progress: One of the union's most crucial objectives is to promote sustainable development, economic growth, and social progress across member states, addressing issues such as poverty, inequality, and unemployment.

- Maintaining Peace and Stability: The AMU aspires to contribute to peace and stability in the region by fostering a collaborative approach based on justice and equity, reducing the likelihood of conflicts that could arise from border disputes or political disagreements.

- Implementing a Unified Foreign Policy: A long-term objective is to pursue common policies in various domains, such as defense, environmental protection, foreign relations, and energy, that would enable member states to present a united front on the global stage.

- Facilitating Free Movement and Trade: The AMU seeks to achieve the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital within the region, ultimately creating a borderless economic zone akin to the European Union (EU). This would enhance trade and cooperation and reduce barriers to economic integration.

Despite its ambitious objectives, the AMU has struggled to make significant progress, primarily due to a series of long-standing challenges. These obstacles have limited the union's effectiveness and raised questions about its future viability. Tensions between member states, particularly between Algeria and Morocco, have been a major impediment to the AMU’s progress. The Western Sahara conflict, in which Morocco claims sovereignty over the disputed territory, while Algeria supports the independence movement of the region, has been a major source of friction. This ongoing dispute has not only strained Algerian-Moroccan relations but has also created rifts within the AMU, undermining efforts at unity. Also, AMU member states have often pursued different, and sometimes conflicting, political and ideological agendas. Libya, for example, under Muammar Gaddafi, was often torn between pan-Maghreb ambitions and its orientation toward Arab solidarity focused on Egypt and the Middle East. Mauritania, geographically isolated by the Sahara Desert, has maintained stronger economic ties with Sub-Saharan Africa, which at times has made its role within the AMU ambiguous [Source: UNECA, AMU].

There are also economic challenges. North African economies have historically been reliant on some sectors, such as oil and gas (for Algeria and Libya) and agriculture (for Morocco and Tunisia), resulting in limited economic diversity. The lack of complementary industries, combined with insufficient infrastructure for regional trade, has hampered economic integration efforts. The region has recently faced significant external challenges, including international sanctions on Libya and political instability stemming from broader Middle Eastern crises. UN-imposed sanctions on Libya in the 1990s and 2000s created isolation for the country, reducing its participation in the AMU and impacting the union's overall functionality. Additionally, political instability within member states, such as the Algerian civil conflict in the 1990s, has disrupted AMU meetings and initiatives. Lastly, the AMU has not developed strong structures to enforce its policies and directives. Summits and meetings are irregular, and the AMU lacks the financial resources and political backing needed to implement its ambitious agenda [Source: UNECA, AMU, and Finaish, M.A., Bell, E. (1994).].

Today, the AMU remains largely inactive, with its institutions dormant and its objectives largely unfulfilled. Despite the hopes generated by the Marrakech Treaty of 1989 and subsequent summits, including meetings in Tunis, Algiers, Ras Lanouf, Casablanca, Nouakchott, and Tunis from 1990 to 1994, the AMU has been unable to overcome internal divisions and external challenges. Several recent developments, however, hint at opportunities for revitalization. The political landscape in North Africa has shifted, particularly following the Arab Spring, which brought social and political changes to Tunisia, Libya, and other parts of the region. Tunisia has emerged as a relatively stable democracy, fostering hopes that it could play a leadership role in reviving the AMU. Additionally, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement, which includes all five AMU countries, could provide a framework for increased regional cooperation and trade, potentially complementing the AMU’s goals. Nonetheless, substantial hurdles remain. The Western Sahara issue continues to be a significant barrier to Algerian-Moroccan cooperation, and Libya remains politically fragmented following years of civil war. Without a resolution to these core disputes, the AMU’s future remains uncertain [Source: UNECA, AMU].

As of October 2024, AMU has 5 member States:

- Morocco

- Algeria

- Tunisia

- Libya

- Mauritania

Structure and organizations of AMU

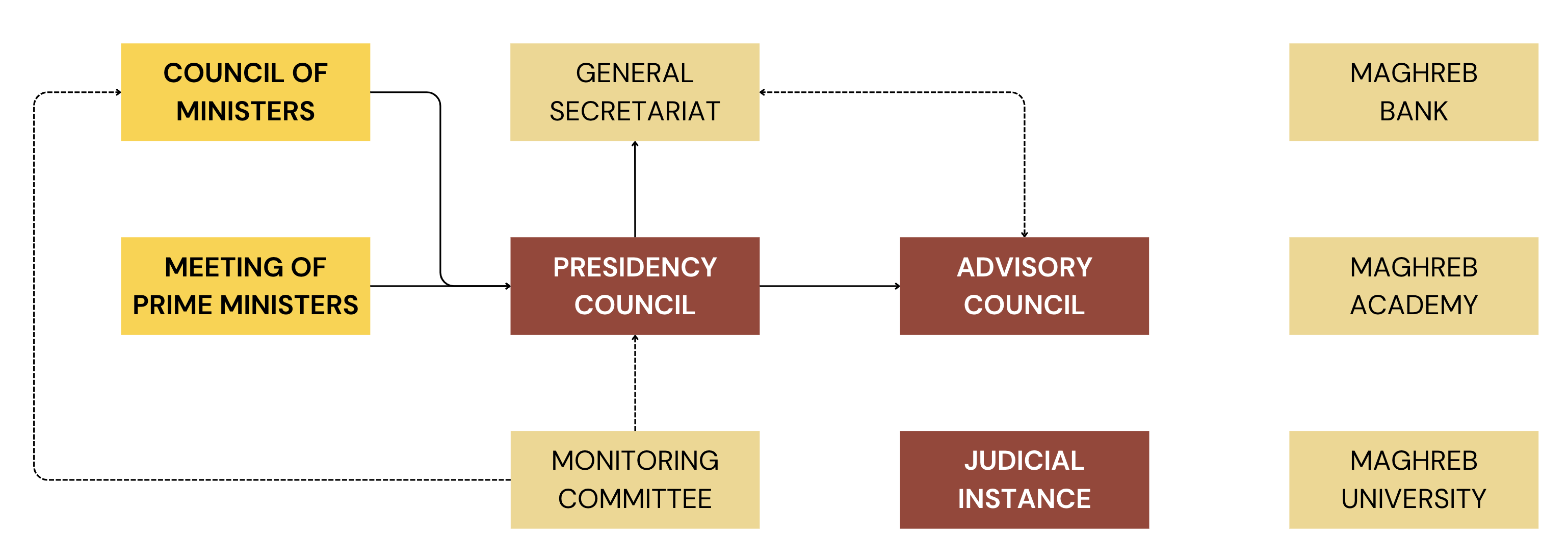

The Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) was created to foster unity and economic cooperation among North African countries. The AMU was built with a complex structure of institutions that reflect its (now largely disregarded) aspirations for unity and cooperation. The Presidency Council is the supreme decision-making body within the AMU, consisting of the Heads of State from each member country. This council holds ultimate authority and is responsible for making decisions on all significant matters concerning the union. Decisions made by the Presidency Council require unanimity, reflecting the union's commitment to consensus-driven governance [Source: AMU, Institutions]. The Presidency Council convenes in an ordinary session once a year but may hold special sessions when necessary. Each member state takes turns chairing the council on a rotational basis, with each term lasting one year. This rotational system aims to maintain balance among the member states, giving each nation an equal opportunity to lead. [Source: AMU, The Presidency Council] The Meeting of Prime Ministers, as its name suggests, is a gathering of the prime ministers or their equivalents from each member state. This meeting provides an opportunity for the heads of government to discuss issues of mutual concern and coordinate policies across their respective administrations. [Source: AMU, The Meeting of Prime Ministers] While the Presidency Council handles the highest level of decision-making, the Meeting of Prime Ministers serves as an intermediary platform where executive leaders from member states can meet as frequently as necessary to address pressing issues or plan joint initiatives. The Council of Foreign Ministers is responsible for preparing sessions of the Presidency Council. This council examines proposals from other AMU bodies, such as the Monitoring Committee and the specialized ministerial committees, before presenting them to the Presidency Council. The Council of Foreign Ministers held its last known session on November 30, 2007, in Rabat, Morocco, at the AMU's General Secretariat headquarters. Each country appoints a representative to this council, who manages the nation's interactions with the AMU and ensures that its interests are addressed. The Council of Foreign Ministers plays a vital role in shaping the AMU’s agenda and aligning the organization's policies with the member states' foreign policies [Source: AMU, The Council of Foreign Ministers].

The Monitoring Committee, also known as the Follow-up Committee, consists of representatives from each member state's government. This committee reviews the implementation of the AMU’s policies, ensuring that the decisions made by higher bodies are put into practice. The Monitoring Committee reports its findings and recommendations to the Council of Foreign Ministers. It last convened on November 29, 2007, at the General Secretariat headquarters in Rabat. By maintaining oversight of the union’s initiatives, the Monitoring Committee is meant to provide continuity and track progress, though in practice, its activities have been limited due to political issues among member states [Source: AMU, The Follow-Up Committee]. The General Secretary of the AMU, headquartered in Rabat, serves as the union's primary administrative office. Established by the Presidency Council, the General Secretariat is responsible for coordinating the day-to-day activities of the AMU and implementing the policies set by the council. The position of Secretary-General rotates among member states, reflecting the union's principle of equal representation. The Secretary-General oversees the operational functions of the AMU, including communication between member states and organizing meetings. As of now, the Secretary-General is Tunisian diplomat Taïeb Baccouche [Source: AMU, The Secretary General]. The Advisory Council provides a forum for representatives from each member state, who are chosen either by legislative institutions or according to each state’s internal rules. Comprising 301 representatives per country, the council meets annually in an ordinary session and may convene in extraordinary sessions upon request by the Presidency Council. The Advisory Council is responsible for delivering opinions on any decision submitted by the Presidency Council and can also issue recommendations to support the AMU’s objectives. The council is headquartered in Algiers, Algeria. Although its role is advisory, it is intended to enhance the democratic legitimacy of the union’s decisions and ensure that the voices of the member states are represented [Source: AMU, The Advisory Council].

The Judicial Instance of the AMU is an independent judicial body composed of two judges from each member state. Judges are appointed for six-year terms, with half of them being renewed every two years. This institution is responsible for interpreting the AMU Treaty and resolving disputes related to its application. It can also provide advisory opinions on legal matters when requested by the Presidency Council. The decisions of the Judicial Instance are final and enforceable. Its headquarters are in Nouakchott, Mauritania, establishing it as the AMU’s legal backbone and a mechanism for resolving intra-union disputes. However, like many other AMU institutions, the Judicial Instance has struggled to maintain influence amid political conflicts [Source: AMU, The Judicial Instance]. The Maghreb Bank for Investment and Trade (BMICE) was established to foster economic integration within the AMU. With a declared capital of $500 million, divided equally among the five member states, BMICE aims to promote intra-Maghreb trade and encourage investment in joint projects. By supporting the free movement of goods, services, and capital, the bank aspires to build a competitive and unified Maghreb economy. Headquartered in Tunis, Tunisia, BMICE represents a significant attempt at economic integration. However, the bank’s potential has been largely unrealized due to the political challenges that hinder AMU’s operational capacity [Source: AMU, BMICE]. In addition to the ten main institutions, the AMU established four specialized ministerial committees to address specific issues: the Committee on Food Security, the Committee on Economy and Finance, the Human Development Committee, and the Infrastructure Committee. These committees focus on sectoral priorities, such as agricultural self-sufficiency, economic stability, social development, and infrastructure enhancement. [Source: AMU, Specialized Ministerial Commissions]

Traditional rivalries within the African Maghreb Union (AMU) have posed significant challenges to the REC. For instance, in 1994, Algeria transferred the AMU presidency to Libya due to diplomatic tensions with Morocco and Libya’s consistent refusal to attend AMU meetings in Algiers. Algerian officials justified the decision, citing the AMU Constitutive Act, which mandates annual presidential rotation. Algeria agreed to assume the presidency from Tunisia but was unable to transfer it because the conditions were not met. Following the announcement, Muammar Gaddafi called for the AMU “freezing,” raising concerns about Libya’s stance. There were fears that Libya would exert negative influence over the Union’s presidency. Traditional rivalries between Morocco and Algeria, along with the unresolved Western Sahara sovereignty issue, have prevented union meetings since the early 1990s despite efforts to resume the political process. Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony invaded by Morocco and Mauritania, declared independence as the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. The most recent high-level conference, held in mid-2005, was disrupted by Morocco’s refusal to attend due to Algeria’s advocacy for Sahrawi independence. Algeria has consistently supported the Polisario Front’s liberation movement. Several attempts have been made to resolve the Western Sahara conflict, notably through the efforts of the United Nations. In mid-2003, the UN Secretary-General’s Personal Envoy, James Baker, proposed a settlement plan, known as the Baker Plan II. While the UN’s proposal was rejected by Morocco, it was accepted by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic [Source: UNECA, AMU, and Finaish, M.A., Bell, E. (1994).].

Regarding bilateral efforts, progress has been extremely limited. Morocco has consistently refused to concede any concessions that would grant Western Sahara independence, while Algeria maintains its unwavering support for the Sahrawis’ self-determination. Furthermore, the conflict between Libya and Mauritania has exacerbated the situation, with Mauritania accusing the Libyan secret service of involvement in a 2003 attempted coup against President Maaouya Ould Sid’Ahmed Taya. Libya has vehemently denied these accusations. In April 2024, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya engaged in discussions regarding the establishment of a new North African entity, intended to succeed the Arab Maghreb Union, which they perceive as inoperative without the participation of Morocco and Mauritania. Joint working groups will be formed to coordinate efforts on securing common borders in response to irregular migration. Furthermore, substantial joint investment projects will be established in cereal production and seawater desalination due to climate change. Additionally, the free movement of goods and people between the three countries will be facilitated. In November 2024, the Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune extended an invitation to Kais Saied, President of Tunisia, Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, President of Mauritania, Mohamed al-Menfi, President of the Libyan Presidential Council, and Ibrahim Ghali, President of the Sahrawi Republic, to attend the celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Declaration of November 1, 1954. This gathering could mark the beginning of a new union [Source: UNECA, AMU, and Finaish, M.A., Bell, E. (1994).].

Most important projects of AMU

The AMU’s Constitutive Treaty outlines several objectives aimed at fostering cooperation and integration among member states. Among these objectives are:

- Strengthening Fraternal Ties and Defending Rights: The AMU seeks to consolidate the fraternal relationships between its member states, improve the welfare of their citizens, and defend their collective rights.

- Free Movement of People, Goods, Services, and Capital: A central goal is to facilitate the free movement of persons, goods, services, and capital within the region, promoting economic interdependence.

- Adoption of a Common Policy in Various Sectors: The treaty aims to establish common policies, particularly in economic areas such as industrial, agricultural, commercial, and social development.

The objective of the AMU is the establishment of a Maghreb Economic Union. This ambitious goal would involve forming a free trade area, a customs union with a common external tariff, and a common market allowing unrestricted movement of production factors. Unlike the Greater Arab Free Trade Area (GAFTA), which aims for financial and monetary unity, the AMU does not explicitly include provisions for financial convergence or a single currency. To achieve its goals, the AMU has outlined several projects and steps to boost regional economic integration and cooperation. Trade liberalization has been a primary goal since the AMU's inception. Plans to dismantle all tariff and non-tariff barriers and establish a free trade area have been in place for decades, yet progress has been slow. While member states have recently been negotiating this free trade area, they have yet to finalize the rules of origin, which are crucial for determining the products eligible for tariff exemptions. The AMU envisions a customs union with a shared external tariff, followed by the establishment of a common market. A common market would integrate the economies of the Maghreb, allowing free movement of persons, services, goods, and capital across borders. However, significant steps toward these objectives remain unfulfilled due to political and practical hurdles. In December 2009, AMU member states decided to create the Maghreb Bank for Investment and Foreign Trade (BMICE) to support regional financial integration and strengthen intra-regional trade. Inaugurated in 2015 with a net capital of $150 million, the bank was designed to fund infrastructure, transportation, telecommunications, and energy projects, all of which are vital for economic integration. In June 2012, AMU states agreed on a plan to enhance economic integration by promoting investment in infrastructure, harmonizing customs procedures, and expanding logistics and transport services across borders. This initiative aimed to address the low level of intra-regional trade, which was just 4.8% of total regional trade in 2012, significantly lower than in other regional economic communities [Source: AMU, The Treaty of Marrakech].

Although trade liberalization was a founding objective of the AMU, progress toward this goal has been slow. The free trade area is not yet operational, and while negotiations are ongoing, there has been limited success in finalizing essential components like rules of origin. Efforts to harmonize customs procedures and establish consistent trade regulations have likewise faced delays. The AMU lacks a clear framework for financial and macroeconomic convergence, which has limited economic integration. Without provisions for a common currency or coordinated financial policies, the AMU’s progress toward a cohesive economic union remains limited. This absence of financial integration has created obstacles for achieving the overarching goal of an economically unified Maghreb [Source: UNECA, AMU].

The Article 2 of Marrakech Treaty emphasizes preserving peace, justice, and security in the region. To promote these values, the AMU established the Council of Common Defense in 1991, with the aim of providing a platform for resolving regional conflicts. In March 2012, the AMU held meetings to discuss ways to fight terrorism, organized crime, and enhance regional security cooperation. While these initiatives have had limited success, gradual progress has been seen, such as Tunisia’s relatively successful transition to democracy. Despite these objectives and initiatives, the AMU has encountered numerous challenges that have hindered its progress toward economic and political integration [Source: AMU, The Treaty of Marrakech]. While the AMU aimed to serve as a forum for conflict resolution, it has struggled to mediate effectively in the region’s social and political crises. Instances of intervention in domestic issues have been rare, and recent security threats, such as terrorism and organized crime, have further complicated the AMU’s role as a peacekeeping body. Despite forming institutions to address these issues, AMU initiatives have yet to yield substantial results. Political instability in the region, particularly following the Arab Spring, has severely impacted the AMU's effectiveness. Recent turmoil in Libya, the political transition in Tunisia, and ongoing disputes between Algeria and Morocco have impeded trade and integration efforts. These internal conflicts have not only prevented regular meetings but also complicated collaboration on essential issues. Lastly, the membership of AMU states in other regional organizations, such as the Grain And Feed Trade Association (GAFTA), has also hindered the AMU’s goals. Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia are members of GAFTA, which removes intra-regional tariffs among Arab League countries. This overlap reduces incentives for an AMU-specific free trade area, as the member states already benefit from GAFTA’s tariff eliminations [Source: UNECA, AMU].

AMU and Free Movement of People

The AMU Constitutive Treaty emphasizes the progressive realization of free movement as a primary objective, recognizing that easing travel restrictions among member states would promote unity and economic interdependence. To achieve this, AMU aims to remove visa requirements, simplify residence procedures, and improve infrastructure to facilitate cross-border travel. Ideally, the AMU envisions a region where citizens can travel, work, and reside in any member state without significant bureaucratic or legal barriers. Despite AMU’s vision, only three of its five member states — Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia — have implemented the freedom of movement protocol to some extent. Among these, Tunisia stands out as the most open, allowing citizens from fellow AMU states to enter its territory freely, without the need for visas. This level of openness aligns with Tunisia’s broader commitment to regional integration and has positioned it as a leader in the AMU for promoting free movement. In contrast, other member states have adopted more restrictive policies. For example, while Libya and Morocco have taken steps toward freer movement, they still require travel visas for citizens of some member states. Additionally, all AMU countries, except Tunisia, mandate that citizens from other member states obtain residence permits — whether temporary or permanent — to reside within their borders. This requirement complicates the goal of seamless mobility within the AMU, as individuals still face bureaucratic hurdles to live and work across borders [Source: UNECA, AMU – Free Movement of People].

Several factors have impeded AMU’s progress toward a fully operational free movement scheme. Security concerns rank high among these obstacles. AMU member states frequently cite regional security issues, including threats from terrorism, organized crime, and political instability, as reasons for delaying full implementation. For instance, Libya’s ongoing instability has created a complex security landscape, with roadblocks and checkpoints set up by both official national security forces and unauthorized groups. These roadblocks, along with other security barriers, hinder cross-border travel and make regional integration efforts more challenging. Another significant barrier is the region’s inadequate infrastructure, particularly in road transport. The prevalence of roadblocks and illegal checkpoints disrupts movement across borders and highlights the need for improved and secure transportation networks. Without significant infrastructure investments, especially in border areas, the dream of free movement will remain difficult to realize.

Among AMU countries, Mauritania holds a high position on the African Visa Openness Index (AVOI), ranking within Africa’s top 10 for visa openness. Morocco’s score showed improvement in 2023, while Algeria’s remained static, and Tunisia’s slightly declined. Nevertheless, Tunisia is the second-highest ranked country within the AMU on the AVOI and remains especially open to citizens from other AMU countries. The visa regime across AMU states generally favors AMU members over countries outside the region, underscoring a preference for regional cohesion [Source: UNECA, AMU – Free Movement of People].

AMU’s overall visa-free reciprocity score, which measures the extent to which member states allow each other’s citizens visa-free entry, is at 60%. This score places the AMU in the upper half of African RECs in terms of member countries granting visa-free access to each other. Notably, Tunisia offers the highest level of visa-free reciprocity within the AMU, allowing all other AMU members visa-free entry and enjoying the same in return. Algeria follows closely, offering visa-free entry to all AMU members, with three countries reciprocating. However, despite some progress, there remains room for improvement in creating a seamless movement environment [Source: UNECA, AMU – Free Movement of People].