The Freemove Project, directed by Prof. Diego Acosta and Dr. Luuk Van Baaren, is an initiative that compiles data on international institutions and agreements that advocate for the free movement of people worldwide. This data is translated into an interactive atlas, allowing for an easily navigable portrayal of different free movement regimes, each comprising extensive information, creating a distinct tool for scholars and agencies alike to utilize in their respective fields and learn from in the context of human mobility. For Africa, the atlas details the various bilateral, multilateral, and continental free movement agreements that exist within the continent. This atlas presents a comprehensive overview of current free movement efforts, enabling informed discussions that assess the impact of existing free movement legislation and inform future improvements to enhance its effectiveness.

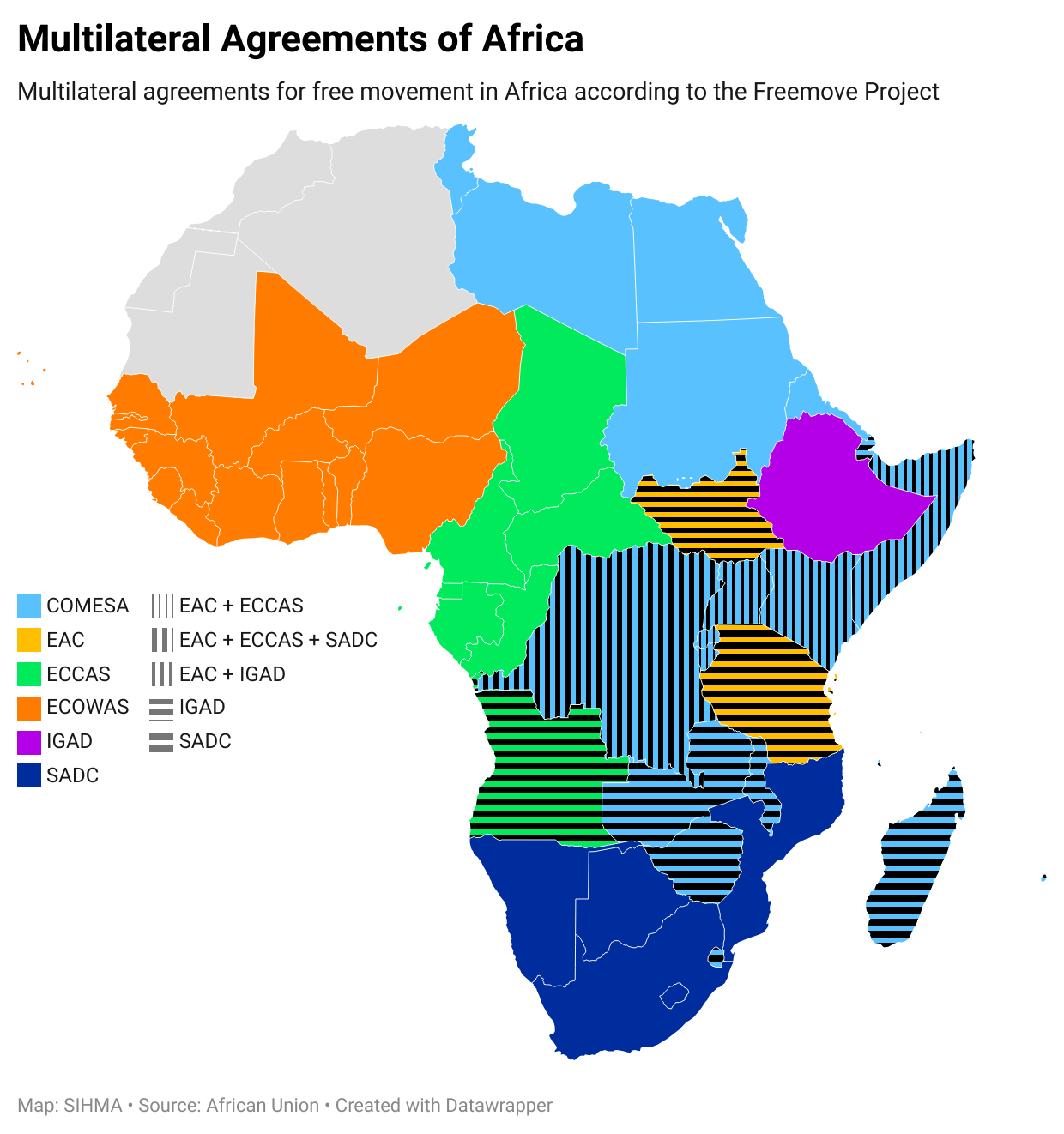

The various multilateral regimes that are outlined in the Freemove atlas are agreements that promote economic and political mobility between countries. An example of this is the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), one of eight multilateral economic communities recognized by the African Union (AU). The agreement encompasses most West African nations, promoting economic cooperation, and in 1993, expanded to include political collaboration as well (Acosta & Baaren, 2024). Notably, most multilateral economic agreements in Africa do not explicitly encourage the free movement of people, except for the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU ), which represents a condition that other multilateral regimes could improve upon (Acosta & Baaren, 2024). Comparing the free movement policy of WAEMU and ECOWAS, the former explicitly advocates for “the free circulation of people, goods, services, capital and settlement rights”, while ECOWAS and other multilateral agreements do not emphasize the free circulation of goods and services for shared economic benefits (Acosta & Baaren, 2024). However, these economic agreements are still beneficial for free movement due to their emphasis on economic integration, which can create a necessity for labor to move freely with firms across borders.

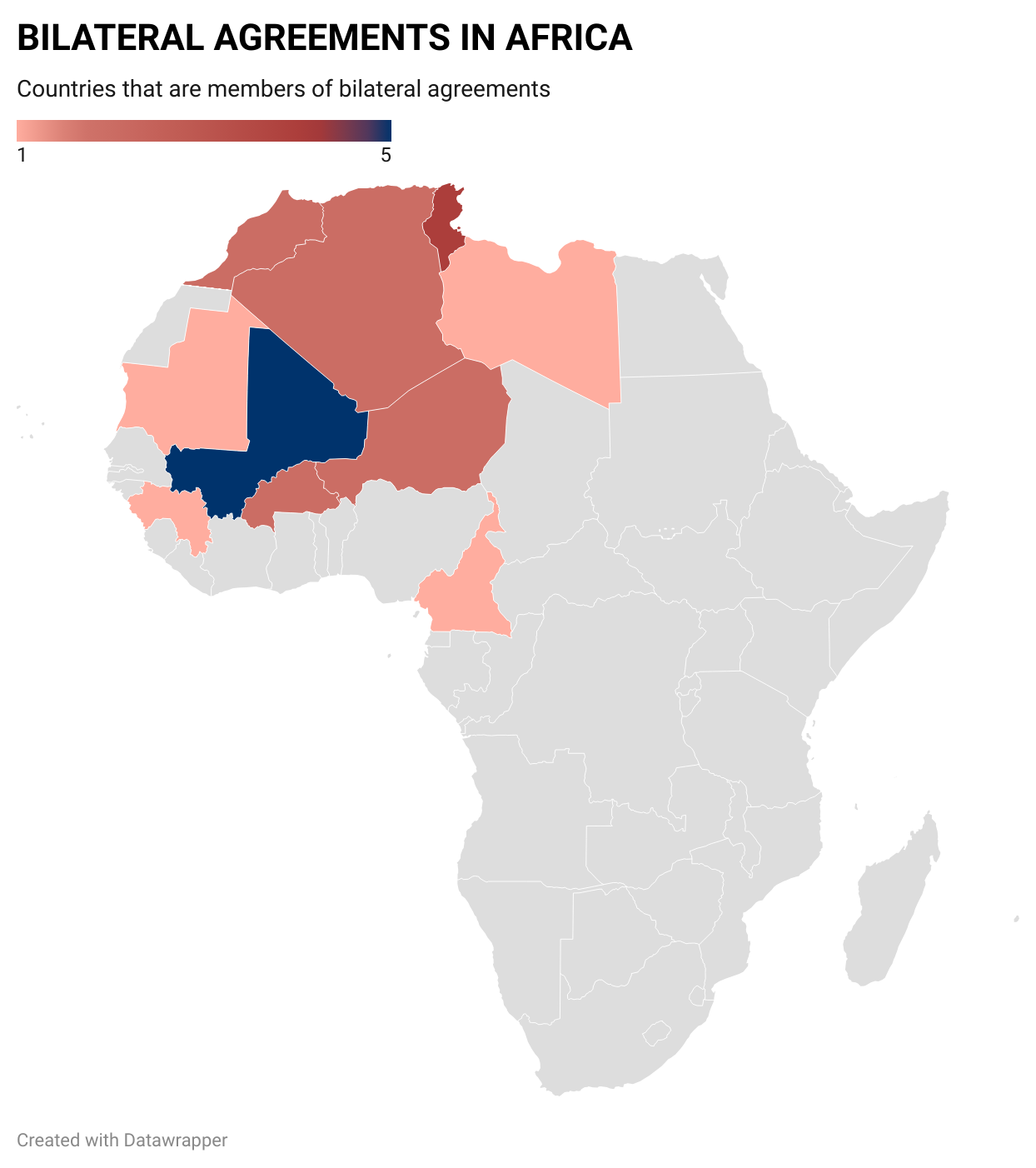

Bilateral agreements in Africa, which are agreements that exist only between two countries, typically explicitly advocate for human mobility. Every bilateral agreement on paper allows nationals from their respective countries to move freely between the two member nations, with some agreements providing special statuses to those nationals (Acosta & Baaren, 2024). The main stipulation surrounding bilateral agreements is their unknown ratification status, which occurs in four out of the ten agreements (Acosta & Baaren, 2024). Specifically, those agreements are between Mali-Cameroon, Mali-Guinea, Mali-Burkina Faso, and Libya-Tunisia. The ratification status refers to the formal implementation of a treaty, or in this case, a bilateral agreement. On paper, there is a legally binding agreement, but in reality, the countries involved do not enforce it. Additionally, situations can change, for example, Mali and Cameroon revised their bilateral agreement in 2015 mainly due to clashing restrictions on air travel. However, the new agreement also restricts free movement and requires VISAS for nationals to travel between the two countries (Acosta & Baaren, 2024 ). Bilateral agreements have a larger emphasis on free movement compared to multilateral ones, but there is still room for improvement in their implementation.

Interestingly, most countries that are not involved in multilateral agreements are heavily engaged in bilateral agreements. For example, every country that is not part of a multilateral agreement - Algeria, Morocco, and Mauritania - is a member of a bilateral agreement. Additionally, bilateral agreements are limited to West and North Africa, with Cameroon being the southernmost country involved in a bilateral agreement (Acosta & Baaren, 2024). This phenomenon of polarity between multilateral and bilateral agreements is most likely caused by the latter preceding the former, as North African countries implemented bilateral agreements in the 1960s. In comparison, the rest of Africa created multilateral agreements in the 1980s and 2000s. Countries involved in pre-existing bilateral agreements don’t have much incentive to join a multilateral one, as explained by Kingster University, “They are easier to negotiate than multilateral trade agreements because they affect only two countries.” (Naveendra, 2019). An antedating agreement with increased autonomy explains why a shift towards multilateral agreements is not as attractive as the system already in place for North African countries and is the one reason why this phenomenon exists.

The last type of regime outlined in the Freemove interactive atlas is the continental regime, which is the African Union. The African Union, founded in 2001, represents all 55 nations in Africa, intending to promote unity and solidarity among African nations through political and economic integration. The Protocol to the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community, Relating to the Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence, and Right of Establishment, is an initiative spearheaded by the African Union (AU) and was created in 2018. It aims to progressively implement the free movement of persons across Africa (African Union, 2018). Free movement is merely a facet of the already expanding free trade initiatives across Africa, which continually support and strengthen the emerging economies on the continent. A study by the AU and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) concluded that a gradual, step-by-step implementation of free movement policies could increase trade, tourism, and industrialization while allowing states to assess the costs and benefits of the free movement protocol (African Union, 2018). Since 2018, 32 African countries have adopted the protocol, but only four have ratified it, which falls short of the 15 signatures required for its enforcement; the most significant factors slowing the protocol’s implementation being political qualms, a lack of awareness, sovereignty concerns surrounding the notion of free movement, and ambiguity regarding its implementation (UNECA, 2023).

The Freemove Project Atlas provides further information on African mobility, serving as an extension of, but not directly affiliated with, the SIHMA Atlas of African Migration, which details the number of refugees, migrants, IDPs, and other relevant migration data on a national level of analysis. The Freemove atlas designs an institutional framework that can help explain the data compiled in the SIHMA atlas, providing a deeper understanding of human mobility trends in Africa. The Freemove atlas also details the institutions in Africa that can promote human mobility and provides examples of the benefits of human mobility, as well as guidance on how to implement such policies. Free movement is a dynamic policy in Africa that has proven to offer benefits to those who adopt it and to people on the move, demonstrating that future progress around free movement can benefit countries, economies, and people across the continent.

Caption

This is a summary of the freemove project’s interactive atlas that highlights different regimes and agreements that promote the free movement of people around the world. Specifically, this article solely focuses on the African continent, revealing the different free movement initiatives that exist on the continent, as well as a breakdown of how those agreements function. The Freemove atlas project correlates with the values of SIHMA, serving as an extension of our own work, as well as a resource that can be utilized by our team and by other organizations that fight for the freedoms of people across Africa and beyond.

Reference

African Union. (2023). Study on advantages and challenges of the Free Movement Protocol (FMP) (Working document No. 43251). African Union. Retrieved July 4, 2025, from https://au.int/sites/default/files/newsevents/workingdocuments/43251-wd-Study_on_Advantages_and_Challenges_of_FMP.pdf

Diego Acosta and Luuk van der Baaren. 2024. Free Movement Regimes Dataset: Indicators on entry, residence, rights, and security of residence. Freemove Project, from www.freemovehub.com

Naveendra. 2019. Bilateral Agreement I. Students Welfare, University of Sri Jayewardenepura. Retrieved July 4, 2025, from https://welfare.sjp.ac.lk/bilateral-agreement-i/

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (2023, March 29–30). Experts’ Group Meeting (EGM) to Review Policy Report on Free Movement of Persons for Trade: Towards an Accelerated Ratification of the AU Free Movement of Persons Protocol in support of the implementation of the AfCFTA. Nairobi, Kenya. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https://www.uneca.org/eca-events/experts-group-meeting-egm-review-policy-report-free-movement-persons-trade-towards-accelerated