Historical Background

Historical Background

Zimbabwe, once considered one of the breadbasket nations in Africa, feeding its population and assisting neighbouring countries, is now a food aid-receiving country (UNHCR, 2019). During the colonial era, Zimbabwe was considered a destination country as it attracted migrants from the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe who desired to settle permanently. These migrants established farms, plantations, and mines that later became a source of employment attracting migrants within the Southern African region who were temporarily recruited to work in the mines, on commercial farms, and for domestic services (Zinyama, 1990). Prior to this, in the 19th century, Zimbabwe was host to migrants fleeing the Mfecane/Difaqane persecution in South Africa (Mlambo, 2010).

Since independence in 1980, Zimbabwe has seen two waves of out-migration. The first wave occurred immediately after independence when many, especially whites, left to avoid the new black majority government while the second wave was driven by the increasing punitive measures of the Mugabe-led government (UNHCR, 2020). The economic decline since 1997 saw Zimbabwe’s macroeconomic environment deteriorate progressively into a hyperinflationary environment resulting in unstable socio-economic conditions that plunged the country into its worst economic crisis in a decade. This crisis rendered life a struggle with necessities – including food, energy for homes, fuel, cash, and medicine – in short supply, which compounded the second wave (Munangagwa, 2009). The once prosperous country sank into an economic decline to the extent that its national currency (the Zimbabwe dollar), lost value and was discarded as a legal tender and replaced with the US dollar. Although Zimbabwe has introduced a new currency backed by gold to stabilise the current currency, the economic situation in the country is still dire, and migration is used by many as a source of livelihood.

Migration Policies

Migration Policies

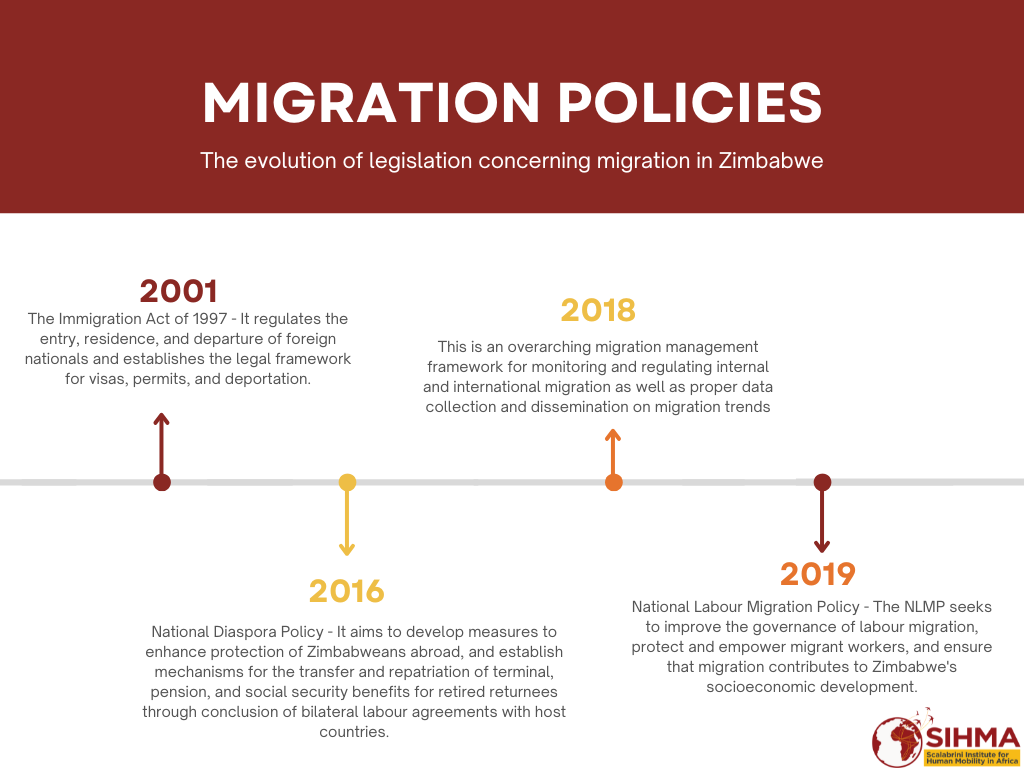

On the national front, the Immigration Act of 1997, amended in 2001, which is administered by the Minister of Home Affairs, regulates the entry and exit of nationals and foreign nationals in and out of Zimbabwe. The migration trajectory in Zimbabwe has changed significantly over time. These changes prompted the government to respond by joining forces with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to form a new national migration strategy which, after several workshops, resulted in the drafting of a National Migration Management and Diaspora Policy. The national migration strategy team is composed of officials from the Migration and Development Unit of the Ministry of Economic Planning and Investment Promotion, the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare, the Ministry of Justice Legal and Parliamentary Affairs, and the IOM (IOM, 2018). The draft policy has a strong focus on mitigating the challenges the country is facing with the large emigration and cross-border movements. It is also aimed at the retention and return of highly skilled Zimbabwean nationals and the promotion of strategies aimed at opening new channels for the legal migration of low-skilled and semi-skilled workers (ibid).

The 2013 constitution states that the right to have access to basic health care services accrues only to citizens and permanent residents. Refugees and other migrants are excluded. However, the law further states that any person with a chronic disease including migrants has the same right, and that children below the age of 18 and the elderly have the right to health care services (Republic of Zimbabwe, 2013). Section 65 of the 2013 constitution recognises the right to fair and safe labour practices and standards for everyone – citizens as well as non-citizens (ibid). This automatically covers migrant workers. Section 64 further emphasises “the right of everyone to choose and carry on any profession, trade or occupation” in Zimbabwe (ibid). It protects and safeguards the employment rights of workers from undue restriction, unfair and unsafe treatment, and unjustified discrimination. The law also provides for migrant workers' inclusion to form and join trade unions and participate in trade unions.

Timeline of Migration Policies in Zimbabwe. Source: SIHMA

At the regional level, Zimbabwe has a Memorandum of Understanding with South Africa for the facilitation of the recruitment of farm workers for commercial farms in South Africa’s Limpopo Province (Human Rights Watch, 2006). Zimbabwe is also a member of Migration Dialogue for Southern Africa, which aims, among others, to foster cooperation among Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states on migration-related issues, thus enhancing its capacity to manage migration within a regional context.

At the continental level, Zimbabwe ratified the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention) and the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. Zimbabwe is a member of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) which advocates for the suppression of obstacles to the free movement of people, as well as the recognition of the establishment and residence of migrants among member states.

On the international front, Zimbabwe is a party to the international convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, the Geneva Convention relating to the status of refugees (1951), the New York Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (1967), the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (Palermo Protocol) (2000), the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and the International Convention on the Rights of the Child. These international instruments protect all human beings regardless of their nationality.

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

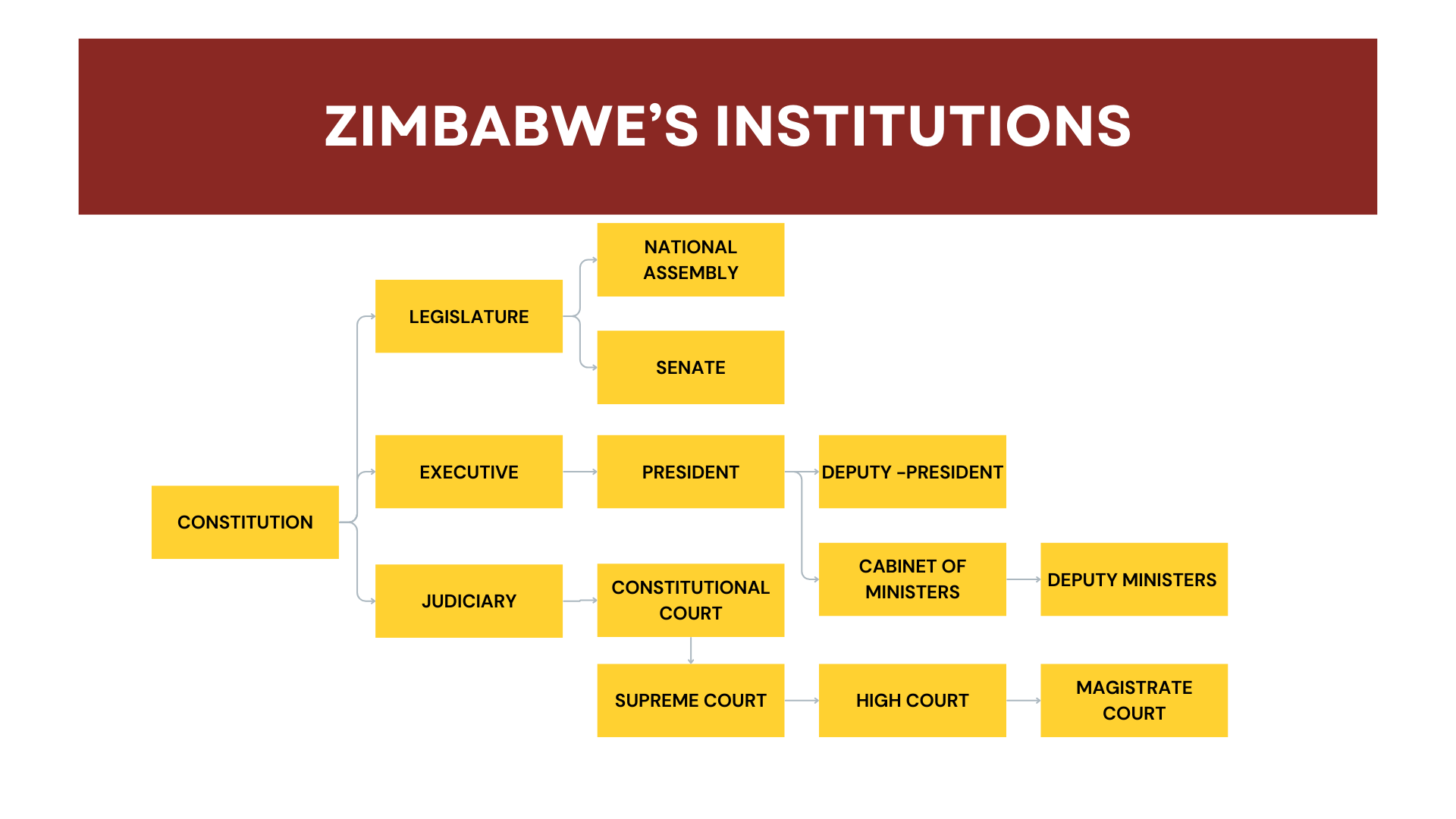

The Zimbabwe National Statistic Agency (ZIMSTAT) is responsible for the country’s population census. The Ministry of Home Affairs and Cultural Heritage is in charge of the identification of all people living in Zimbabwe. The Ministry of Home Affairs is also responsible for maintaining public order and security as the Department of Police falls under this Ministry. It also controls the entry and exit of people across Zimbabwean borders and is in charge of the issuance of personal documents like passports and refugee permits. Refugee protection is governed by the Ministry of Public Service, Labour, and Social Welfare.

Zimbabwe's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

The National Plan of Action is the implementation tool of the Trafficking in Persons Act underpinned by four pillars: prosecution, prevention, protection, and partnership. The Zimbabwe Refugee Committee (ZRC) is the national body mandated under the Refugee Act to conduct refugee status determination (Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Zimbabwe, 2017).

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

Before 1980, the freedom of movement of most Africans in urban areas in Zimbabwe was restricted by colonial rule. However, after independence, factors such as the following contributed to rural-urban migration: the lifting of restrictions on rural-urban migration, the difference in economic opportunities and income between towns and rural communal areas, government development programmes that encouraged urban-based economic development, and the surge in public sector employment (Potts & Mutambirwa, 1990). Despite these changes, for economic and security reasons, such as the high cost of an urban lifestyle and unemployment, migrants maintained rural linkages as a form of livelihood security on which to fall back (ibid). Kurete (2019) posited that the absence of such urban-rural linkages increases the vulnerability of urban migrants. Migrants are therefore moving back and forth between their rural and urban set-ups. In 2020, 32.24% of Zimbabwe's total population lived in urban areas (Statista, 2022). Border towns such as Matabeleland which hosts Beitbridge sees 7 million people passing through it yearly. This has turned border towns into magnets for rural-urban migration in Zimbabwe as many believe they can earn a living from the millions of people who pass through these border posts (All Africa, 2021). The search for livelihood opportunities remains one of the main drivers of internal migration in Zimbabwe.

Internally Displaced Persons

Internally Displaced Persons

Historically, displacement in Zimbabwe was driven by conflict, development and natural disasters. Currently, displacement is driven by conflict and natural disasters, with natural disasters being the main driver of internal displacement. Even though there is no legal framework that specifically recognises and provides for the protection and assistance of internal displaced persons (IDPs) in Zimbabwe, the 2013 constitution articulates a Bill of Rights that protects the basic rights of IDPs (Ndlovu & Nwauche, 2021). Also, tools like the 2011 framework for the Resettlement of Internally Displaced Persons have been developed to help humanitarian actors to identify and assist displaced people with resettlement solutions (Takaindisa, 2021).

Conflict

From 1980 to 1987, post-independent Zimbabwe saw massive conflict-induced displacement with the Gukurahundi massacres in Matabeleland and Midlands which resulted in thousands of Ndebele people being displaced from the Southwestern part of the country to the crowded cities and beyond (ibid). In 2009, there were 15,000 internally displaced persons in Zimbabwe as a result of conflict and violence. The number dropped to 280 in 2012, and by the end of 2023, no one was reported to have been displaced because of conflict (IDMC, 2023).

Disaster

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC, 2023), at the end of 2022, a total of 139,000 people were internally displaced as a result of disasters. Heavy rains caused flooding and mudslides and destroyed infrastructure in the Manicaland, Mashonaland-East and Central, Matabeleland-South, and Masvingo provinces – displacing people (Floodlist, 2021). Tropical cyclone Dineo hit Tsholosho District in Zimbabwe in February 2017, killing seven persons and destroying more than 4,000 houses and government structures, causing people to be on the move (Mhlanga et al., 2019). Also, the effect of Cyclone Idai, which made landfall in Zimbabwe in 2019, was compounded by heavy rainfall in 2020 and 2021, resulting in the internal displacement of 41,535 people (58% female and 42% male) (International Organisation of Migration & Displacement Tracking Matrix, 2021). The majority of IDPs (97%) at the time were residing in host communities, while a small proportion (3%) were seeking shelter in four established IDP camps (United Nations Central Emergency Response Funds, 2019). Only 18% of the affected population receive emergency support (ibid). Climate variability, which can have a significant negative impact on the agricultural sector of an economy like that of Zimbabwe, spells misery to millions of people whose livelihoods depend on this sector.

Immigration

Immigration

Zimbabwe, in the 1980s, after it had gained independence, became an attraction for foreign nationals as the newly elected leader of the nation, Robert Mugabe, preached hope and reconciliation following a bitter and protracted war for independence. There was economic prosperity in the 1980s. However, this was short-lived as the country started experiencing an economic decline in the late 1990s.

According to a 2019 report by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), there were an estimated 398,300 international migrants in 2010, about 400,500 in 2015, and 411,300 in 2019, with the majority of them coming from Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Data from the Department of Immigration Control shed light on the number of Temporary Employment Permits (TEPs) issued to foreign nationals. Between 2010 and 2016, the Government of Zimbabwe issued 18,436 TEPs to foreign nationals from 74 countries, with the majority (11,272 or 71%) issued to Chinese nationals and South African nationals (1,859), followed by India and Zambia (IOM, 2021a). Although the number of people immigrating to Zimbabwe has reduced over the years, the data indicates that despite the myriad of challenges facing Zimbabwe, the country is still an attractive destination for migrants.

Female Migration

Female Migration

There is no reliable information on the nature of the female immigrant population in Zimbabwe. However, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) provides general statistics on the total female immigrant population in Zimbabwe without any specificities. In 2010, 43% (171,269) of the international migrant stock were women. In 2015, the female international migrant stock stood at 43.7% (175,019) and in 2019, it was estimated to be 43.2% (177,682) (UN DESA, 2019). The data therefore indicates a stable female migration pattern into Zimbabwe.

Children

Children

There is a lack of data on the number of migrant children in Zimbabwe. However, the UNHCR indicates that there are nearly 7,500 refugee children in Zimbabwe (UNHCR, 2022). Zimbabwe is a signatory to the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child which requires the country to provide access to basic services to all children – including migrant children, unaccompanied migrant children, and children of refugees. However, the country’s the Refugee Act (2001) and the Immigration Act (2001) protect refugees and their children under the age of 18 years, thus excluding unaccompanied migrant children. Even though the Children’s Act stipulates that vulnerable children or children in need of care have the right to access basic services through the National Case Management System, the Act is silent on whether unaccompanied migrant children who are non-Zimbabwean are a category of “vulnerable children” or “children in need of care” (IOM, 2017). However, the National Plan for Orphan and Vulnerable Children developed in 2007 included “unaccompanied migrant children” in its definition – as part of those qualified to access basic services in Zimbabwe. The exclusion of unaccompanied children in the various Acts increases the vulnerability of this category of children to exploitation, abuse, human trafficking, and smuggling.

Refugees and Asylum seekers

Refugees and Asylum seekers

With its fair share of problems with locals eager to leave the country, Zimbabwe remains an attractive destination for vulnerable groups – refugees and asylum seekers fleeing persecution in their home country. Zimbabwe hosts refugees that emanate mostly from the Great Lake Regions. Zimbabwe adopts the Camp model of managing refugees.

There are two refugee camps in Zimbabwe: the Tongogara refugee camp in Manicaland Province is the main refugee camp and the Waterfalls refugee transit camp in Harare. The transit camp in Harare provides temporary shelter and other needs to refugees undergoing the status determination process before being transferred to the Tongogara refugee camp (IOM, 2017). Also, some refugees live in urban areas – mainly in Harare. According to the UNHCR (2023), there were 23,132 people of concern in Zimbabwe – more than 50% from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The people of concern in Zimbabwe come from the DRC (12,410), Mozambique (8,310), Rwanda (845), Burundi (966), and others (609) (UNHCR, 2023). Nationals from the Great Lake regions made up more than 85% of asylum seekers and refugees in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe is also host to a small number of refugees from Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia (Ibid).

Emigration

Emigration

There are no updated statistics on the number of Zimbabweans living abroad. While the IOM reports that an estimated 571,970 Zimbabweans were living abroad (IOM, 2018), the Afro Barometer indicates that three to four million Zimbabweans were living abroad (Ndoma, 2017). According to the Migration Data Portal, Zimbabwe is the top country of origin of immigrants residing in Southern Africa (911,981), constituting 14% of the total immigrant population in the region (Migration Data Portal, 2022). The top five destination countries for Zimbabwean international migrants are South Africa, the United Kingdom, Malawi, Australia, and Botswana. However, it is widely acknowledged that these statistics do not provide a full picture of emigration from Zimbabwe because of the circular and irregular nature of emigration (as not all migrants are registered, and some of those registered at times give false information). Due to its proximity to South Africa, Zimbabwe has been a transit country for migrants from countries in the Horn and Central Africa, such as Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea, and Tanzania en route to South Africa (IOM, 2021).

Emigration from Zimbabwe has happened in different waves. The first wave of skilled emigrants (mostly white people) left the country immediately after independence in the early 1980s. The second wave, which started in 1990 and is ongoing, is considered a “brain drain” as thousands of highly skilled Zimbabweans are leaving the country because of the economic decline and political unrest. The hardest-hit sectors are the educational and health care sectors, closely followed by the accounting sector. A study conducted by Afro Barometer revealed that 64% of the respondents with post-secondary or secondary qualifications (55%) are far more likely to emigrate (Ndoma, 2017). The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimated that the emigration of doctors was reaching 51%, and that the main receiving countries were South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and Australia (IOM, 2018). Zimbabwean teachers constitute the largest group of migrant teachers in South Africa – 61% (De Villiers & Weda, 2017). The emigration of skilled professionals is hurting the economy of the country and the provision of services, particularly in sectors like health care and education.

Labour Migration

Labour Migration

Zimbabwe has a long history of labour migration. Besides being a sending and a transit country for labour migrants, Zimbabwe is also a receiver of migrant labour – especially from Malawi, Mozambique, and South Africa. According to the IOM (2020), a labour migration report estimated that there were 78,000 migrant labour workers in Zimbabwe constituting 37.7% of the total migrant population in the country.

To protect migrant workers in Zimbabwe and Zimbabweans living and working abroad, the government initiated the National Labour Migration Policy (NLMP) of Zimbabwe. Despite the progressive nature of the NLMP, Zimbabwe is yet to ratify the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 97 on Migration for Labour and 143 on Migrant Workers Supplementary Provision. Not being a signatory to the ILO Convention 97 and 143 makes migrant labourers in Zimbabwe and Zimbabwean migrant labourers living abroad more vulnerable to exploitation as they have limited access to justice.

Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking

Zimbabwe is a Tier 2 country according to the US Department of State’s Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report. Despite its efforts to combat trafficking, Zimbabwe does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking. For example, the draft amendments to the 2014 Trafficking in Persons Act to bring the law in line with international standards by 2020 have not yet been ratified and the government failed to provide adequate funding to its NGO partners on which it relied to provide protection services to victims of human trafficking (US Department of State, 2024). According to the 2024 Trafficking in Persons Report (2024), “Zimbabwe is a source, transit, and destination country for men, women, and children trafficked for forced labour and sexual exploitation”. In Zimbabwe, children and adults are exploited in sex trafficking and forced labour, especially in agriculture, forestry, and fishing, and also in domestic services and mining (ibid).

In 2024, the government in partnership with NGOs identified and referred four victims to care where they are provided with shelter, food, medical treatment, family reunification and reintegration services, counselling, and income-generating assistance (ibid). The report also indicated that the government did not train adequate numbers of officials like labour inspectors to help with the identification of victims. In the same reporting year (2024), the government initiated 10 investigations of human trafficking, initiated prosecution for eight human trafficking suspects (three for sex and labour trafficking and five for labour trafficking), continued with three prosecutions from the 2023 reporting year and obtained convictions of five traffickers (ibid).

Within Zimbabwe, the worsening economic situation and certain cultural practices contribute to the scourge of human trafficking in the country. Certain traditional practices, for example, replacing brides for deceased family members and avenging the spirit of a murdered relative, rendered young girls vulnerable to forced labour and sex trafficking (ibid). Out of Zimbabwe, traffickers use false promises of legitimate employment opportunities and scholarship schemes to lure Zimbabwean adults and children into sex trafficking and forced labour in South Africa, Iraq, Kenya, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Uganda, the United Kingdom, and Ireland (ibid). The inadequacy of trained officials to help facilitate the identification process of victims of human trafficking means that human trafficking in the country will likely be under-reported. Everything being equal, the dire economic situation in the country and ongoing traditional and cultural practices mean that human trafficking in Zimbabwe will continue.

Remittances

Remittances

The deterioration of the Zimbabwean economy and the subsequent hyperinflation estimated at 231 million percent, resulting in a 94% unemployment rate, has resulted in a mass exodus of Zimbabweans escaping the economic hardship while continuing to support the families they left behind (Truen et al., 2016). According to the World Bank (2022), the remittance flow in Zimbabwe experienced a steady increase from 2009 ($1.21 billion) to its all-time high in 2012 ($2.11 billion). Subsequently, it dropped to $1.42 billion in 2019 and picked up to $1.83 billion in 2020. These are flows through registered formal money transfers and banking channels.

However, informal money transfer channels, including migrants using drivers and passengers crossing the borders, are also increasing. Within Zimbabwe, remittances constituted between 13.6% and 10.1% of GDP from 2011 to 2020 (World Bank, 2022). Even though remittance flow is vulnerable to exogenous shocks, it remains an important contributor to Zimbabwe’s balance of payments as it represents more than twice the amount of Foreign Direct Investment (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021). At the national level, remittance flow positively influences economic development as it serves a catalyst for the rate of capital formation through increased capital inflow (Mubhawu et al., 2018). At the household level, remittance flow has acted as a form of social protection for many families. Remittance flow is therefore an important facet of the development propensity of the country requiring the government to ensure and facilitate its growth through remittance-friendly policies.

Returns and Returnees

Returns and Returnees

According to the IOM (2021b), the Covid-19 pandemic had far-reaching consequences for Zimbabwean emigrants living in the southern region of Africa. These consequences included financial challenges, hunger, loss of accommodation, lack of access to medical assistance and mental health support, identity document issues, and the risk of assault in their host country. As a result, thousands of Zimbabwean emigrants have voluntarily returned home. According to the IOM (2021c), Zimbabwe has received 380,967 returning migrants since the onset of the pandemic. However, from 2018 until 2020, a total of 91,413 Zimbabwe migrants consisting of 19,630 females, 66,140 males, and 5,643 accompanied and unaccompanied minors in irregular migration flows were returned from Botswana and South Africa (IOM, 2021a). At one of the points of entry – the Beitbridge reception and support centre – returnees are supported with services, including food, information, and onward travel to their communities of origin (IOM, 2021c). The IOM argues that the challenges associated with economic reintegration in the host country and making a livelihood could force returnees to resort to irregular migration. In response, the IOM, through its Crisis Response Plan in Zimbabwe, seeks to promote socio-economic reintegration through self-employment, community income projects, and livelihood activities (IOM, 2021a). The reintegration plan for returnees remains an important element in creating an enabling environment for returnees to be reintegrated into their existing communities.

International Organisations

International Organisations

The key players in migration-related matters in Zimbabwe are the following:

• International Organization for Migration (IOM): The government of Zimbabwe recognises IOM Zimbabwe as the principal international inter-governmental organisation addressing the entire spectrum of migration issues.

• UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR): The UN Refugee Agency plays an essential role in migration-related issues in the country as it assists refugees, asylum seekers, and community members in the areas of education, health, food security and nutrition, protection, water sanitation, hygiene, camp coordination and management, access to energy, and community empowerment and self-reliance.

• United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): Helps to create sustainable growth to improve people’s lives.

• United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): Assists refugee children with access to education.

• World Food Programme (WFP): Helps food-insecure people including refugees to meet their basic food and nutrition requirements.

• International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC): Works in the areas of advocacy – promotes the welfare of detainees, including migrants, supports health services, and restores family links separated by disaster.

• Mercy Corps: Provides assistance and relief to people affected by disasters such as Cyclone Idai.

• GOAL: Helps to build resilience and sustainable livelihood by improving health, water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and nutrition systems, supports refugees, and strengthens the value chains needed to foster long-term financial security.

All Africa. 2021. Zimbabwe: Border towns exposed to rural-urban migration. Retrieved from: https://allafrica.com/stories/202104190116.html

Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Zimbabwe (CCJPZ). 2017. Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://www.peaceinsight.org/en/organisations/the-catholic-commission-for-justice-and-peace-in-zimbabwe-ccjpz/

CIA World Factbook. 2025. Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/zimbabwe/

De Villiers, R. & Weda, Z. 2017. Zimbabwean teachers in South Africa: A transient greener pasture. South African Journal of Education, 38(3):1-9.

Equal Times. 2021. Zimbabwe launches National Labour Migration Policy to help protect migrant workers. Accessed: https://www.equaltimes.org/zimbabwe-launches-national-labour

Floodlist. 2021. Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise triggers floods in Mozambique, Zimbabwe and South Africa. Retrieved from: https://floodlist.com/tag/zimbabwe

Human Rights Watch. 2006. Unprotected migrants: Zimbabweans in South Africa’s Limpopo province. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2006/08/09/unprotected-migrants/zimbabweans-south-africas-limpopo-province

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2022. Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/zimbabwe

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2023. Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/zimbabwe

International Organization for Migration (IOM) & Displacement Tracking Matrix. 2021. Zimbabwe - Tropical Cyclone Idai baseline assessment - round 7 (20 April - 13 May 2021). Retrieved from: https://dtm.iom.int/reports/zimbabwe-tropical-cyclone-idai-baseline-assessment-round-7-26-april-13-may-2021

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Study on unaccompanied migrant children in Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://scalabrini.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/International-organisation-for-migration-report.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2018. Migration in Zimbabwe: A country profile 2010 - 2016. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-zimbabwe-country-profile-2010-2016

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2021a. IOM Zimbabwe National Country Strategy 2021 - 2024. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Zim%20National%20Strategy.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2021b. More than 200,000 people return to Zimbabwe as covid-19 impacts regional economies. Retrieved from: https://zimbabwe.iom.int/news/more-200000-people-return-zimbabwe-covid-19-impacts-regional-economies

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2021c. Best practices from Zimbabwe in supporting returned migrants. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/zimbabwe/best-practices-zimbabwe-supporting-returned-migrants

Kurete, F. 2019. SSRN | Vulnerability of rural-urban migrants in Zimbabwe: A case of Bulawayo City. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3334306

Migration Data Portal. 2021. Zimbabwe. Retrieved from https://www.migrationdataportal.org/international-data?i=stock_abs_&t=2020&cm49=716

Mhlanga, C., Muzigili, T. & Mpambela, M. 2019. Natural Disasters in Zimbabwe: The Primer for Social Work Intervention. African Journal of Social Work, 9(1):46-54. Retrieved from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajsw/article/view/184232

Mlambo, A.S. 2010. History of Zimbabwean migration to 1990. In: Crush, J. & Tevera, D., eds. Zimbabwe’s Exodus: Crisis, Migration, Survival. Cape Town: SAMP & Ottawa: IDRC. pp. 52-78. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289335664_History_of_Zimbabwean_Migration

Mubhawu, P., Masere, V. & Gurira, P. 2018. The impact of remittances on economic development in Zimbabwe (2000 – 2015): An econometric model (OLS). Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 9(12):133-145. Retrieved from: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEDS/article/view/43148

Munangagwa, L. 2009. The economic decline of Zimbabwe. The Gettyburg Economic Review, 8(9):110-129. Retrieved from: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=ger

Ndlovu, N. & Nwauche, S. 2021. A review and land and property rights of internally displaced persons in Zimbabwe: Steps towards restitution. In: Adeola, R., ed. National protection of internally displaced persons in Africa. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66884-6_6

Ndoma, S. 2017. Afro Barometer | Almost half of Zimbabweans have considered emigrating; job search is the main pull factor. Retrieved from: https://www.africaportal.org/documents/17708/ab_r6_dispatchno160_zimbabwe_emigration.pdf

Potts, D. & Mutambirwa, C. 1990. Rural-urban linkages in contemporary Harare: Why migrants need their land. Journal of Southern African Studies, 16(4):677-698.

Republic of Zimbabwe. 2013. Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (20). Harare. Retrieved from: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Zimbabwe_2013.pdf

Statista. 2022. Zimbabwe: Urbanization from 2010 to 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/455964/urbanization-in-zimbabwe/

Takaindisa, J. 2021. The political stakes of displacement and migration in/from Zimbabwe. Arnold Bergstraesser Institut. Retrieved from: https://www.arnold-bergstraesser.de/sites/default/files/displacement_zimbabwe_takaindisa.pdf

The Economist Intelligence Unit. 2021. Zimbabwean remittances soar. Retrieved from: http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=1950990578&Country=Zimbabwe&topic=Economy&subtopic=_1

Truen et al. 2016. Finmark Trust | The impact of remittances in Lesotho, Malawi and Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://finmark.org.za/system/documents/files/000/000/247/original/the-impact-of-remittances-in-lesotho-malawi-and-zimbabwe.pdf?1602597191

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2019. International migration stock 2019: South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019. Once the breadbasket of Africa, Zimbabwe now on the brink of man-made starvation, UN rights expert warns. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/zimbabwe/once-breadbasket-africa-zimbabwe-now-brink-man-made-starvation-un-rights-expert

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. Finding home in uncertainty: Reintegration, and reconciliation: A case study of refugees in towns – Harare, Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/zimbabwe/finding-home-uncertainty-returnees-reintegration-and-reconciliation-case-study

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2021. Zimbabwe: Fact Sheet. Retrieved from: http://reporting.unhcr.org/zimbabwe

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Laughter to refugee children and their host in Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/afr/news/stories/2022/6/62a341aa4/unhcr-and-clowns-without-borders-bring-laughter-to-refugee-children-and.html

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023. Zimbabwe: Factsheet. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/zimbabwe/unhcr-zimbabwe-factsheet-january-2023

UN Central Emergency Response Funds (UN CERF). (2019). Resident/humanitarian coordinator report on the use of CERF funds Zimbabwe rapid response Cyclone Idai. Retrieved from: https://cerf.un.org/sites/default/files/resources/19-RR-ZWE-35840-NR02_Zimbabwe_RCHC.Report.pdf

US Department of State. 2022. Trafficking in person report: Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/zimbabwe/

World Bank. 2022. Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Malawi. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=ZW

Zinyama, L. 1990. International migration to and from Zimbabwe and the influence of political changes on population movement, 1965-1987. International Migration Review, 24(4): 748-767.