HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Uganda has been and still is an important country for refugees and asylum seekers. The process of hosting refugees in Uganda can be traced as far back as after the Second World War when the country hosted about 7000 Polish refugees (Wamara, 2021). The Ugandan government has put forward a welcoming narrative both domestically and internationally, based on the idea of helping “brothers” in need and Pan-Africanism (ODI, 2020) and cognizant that many Ugandans, including senior government officials, experienced displacement at some stage. Ugandans understand the plight of refugees. This messaging is broadly echoed by wider actors, including Uganda’s media (Ibid).

Uganda receives refugees from Burundi, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, and many more. According to UNHCR (2023b), the country has hosted more than 1.5 million refugees.

Migration in Uganda has been driven by political factors, poverty, rapid population growth, and the porosity of its international borders (IOM, 2015). After its independence in 1962, Uganda experienced civil war and ethnic strife until the mid-1980s. In 1986, the National Resistance Movement assumed power, and Yoweri Museveni became president, which he still is in 2024. Since then, the country has progressed toward democracy, and its economy has grown (IOM, 2015).

However, Northern Uganda has had to go through some economic and security issues in the last decades. Approximately 1.7 million people in the Acholi region in the north were displaced because of over 20 years of armed conflict between the Lord’s Resistance Army led by Joseph Kony and the Ugandan government. Because of this, and natural disasters and political shocks, the northern regions of Uganda have been underdeveloped relative to the other regions, giving rise to persistent inequality issues in the country. Voluntary internal migration has been a trend in the country throughout history, with the major reason being the search for employment opportunities (IOM, 2015).

Similar ethnicities live across borders, which means that ethnic ties transcend the borders with neighbouring countries. As the borders with these countries are considered quite porous, and as total border surveillance is practically impossible with current resources, unknown immigration and emigration routinely take place (IOM, 2015).

Uganda’s emigration can be understood by using a metaphor of waves. There have been three waves so to speak. The first wave happened while Idi Amin Dada was president when he expelled 80,000 Ugandans of South Asian origin. The second wave happened between 1971 and 1986 when thousands of refugees fled Uganda due to armed conflict and political instability. The third wave is currently happening because of ties with Ugandan diasporas and push and pull factors resulting from globalization’s labour mobility (IOM, 2015).

MIGRATION POLICIES

MIGRATION POLICIES

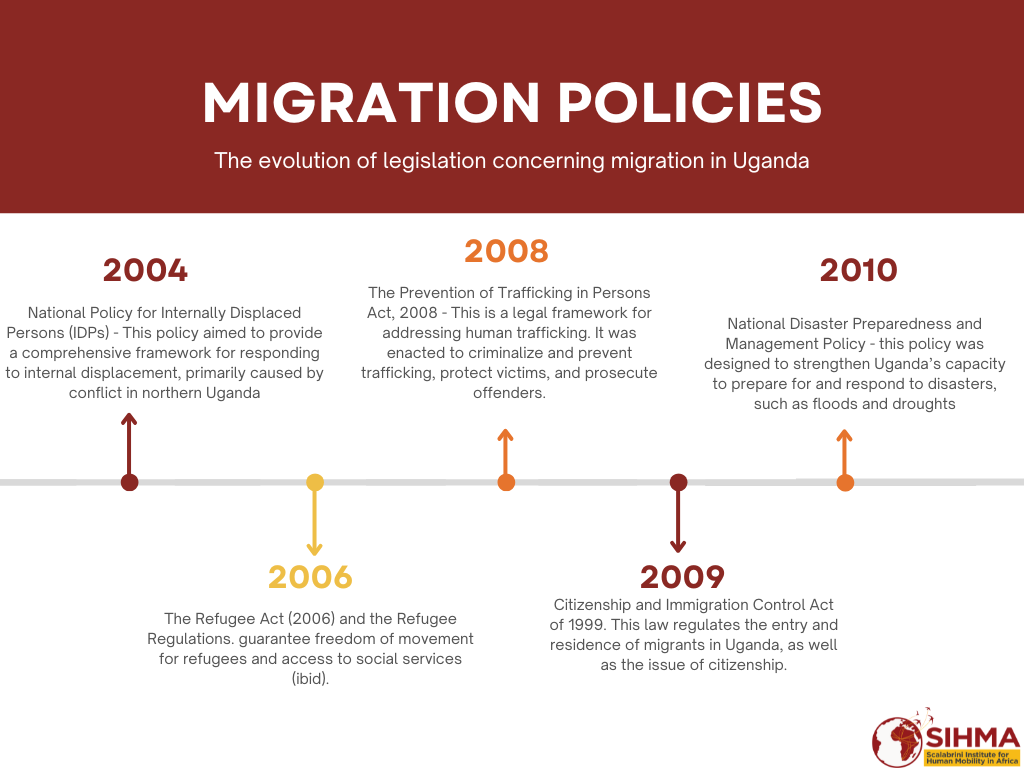

The most important law governing immigration to Uganda is the Citizenship and Immigration Control Act of 1999, amended in 2009. This law regulates the entry and residence of migrants in Uganda, as well as the issue of citizenship. It does not discuss emigration or return migration (IOM, 2015). According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the country’s legal framework is fragmented and does not address all aspects of migration (IOM, 2018a). The Refugee Act (2006) and the Refugee Regulations (2010) guarantee freedom of movement for refugees and access to social services (ibid). These pieces of legislation also allow refugees to apply for permits for a family member to enter and reside in Uganda. Upon registration, refugees receive a plot of land for settlement and agriculture (ibid). When the refugee law was launched in 2006, a model was adopted for Africa, which allowed refugees to live in communities instead of in separate camps (Akello, 2009).

The National Policy for Internally Displaced Persons (2004) and the National Disaster Preparedness and Management Policy (2010) pertain to internally displaced persons, while the Prevention of Trafficking in Persons Act of 2008 is the key legislation pertaining to trafficking in human beings (IOM, 2015).

Timeline of Migration Policies in Uganda. Source: SIHMA

Uganda is a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention on the Status of Refugees 1951, the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, the additional provisions of the ILO Convention on Migrant Workers, and the UN Conventions on Statelessness. Uganda is a party to the African Union Convention for The Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention) and the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa.

Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania, and Kenya were the founding states of the East African Community (EAC). In 2009, Uganda adopted the EAC Common Market Protocol, which allows the free movement of persons and the free movement of workers through the EAC (ibid). Uganda has a Prevention of Trafficking in Persons Act 2008 aimed at combating human trafficking.

GOVERNMENTAL INSTITUTIONS

GOVERNMENTAL INSTITUTIONS

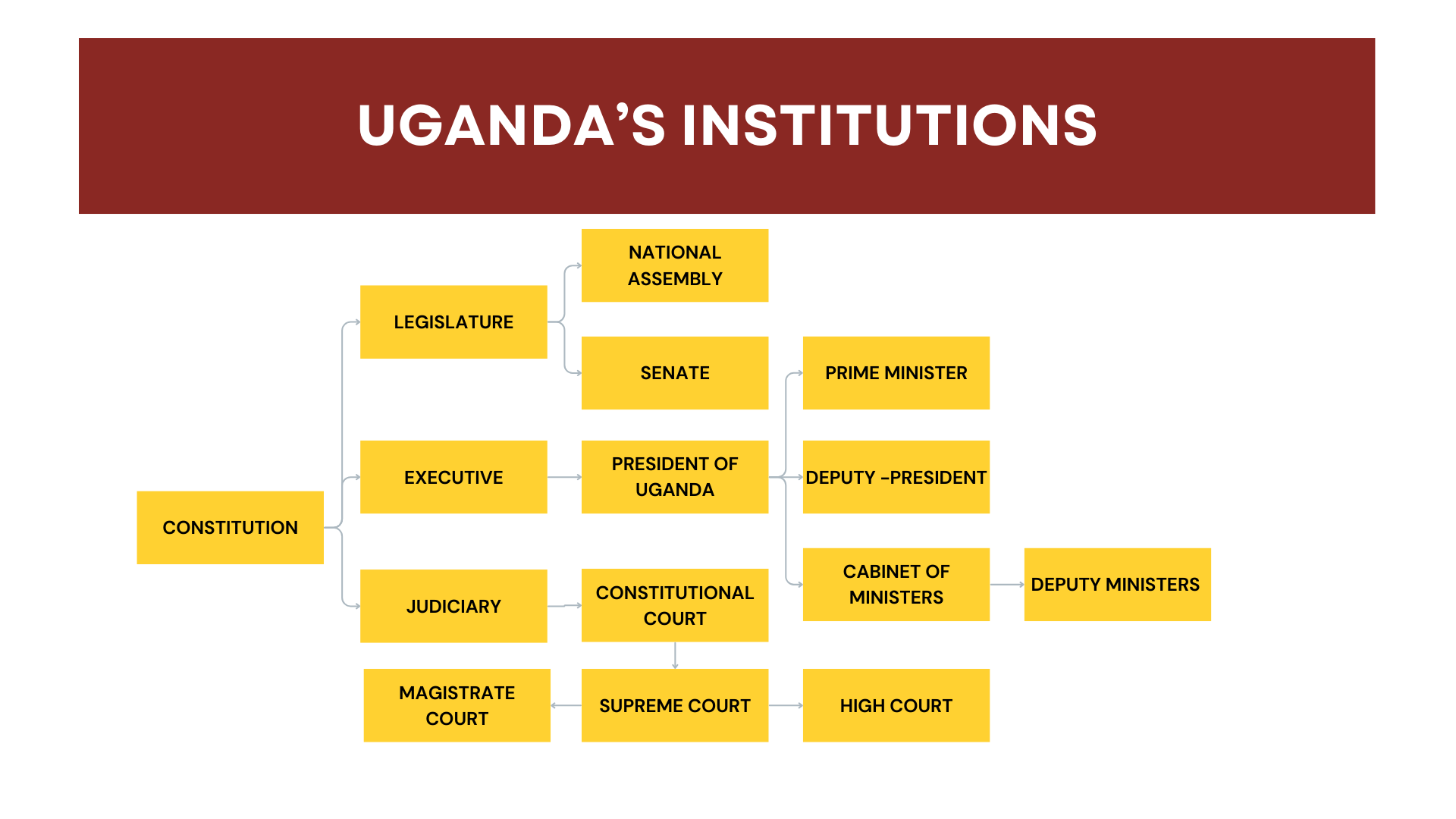

The Ministry of Internal Affairs is responsible for the identification and census of the population. The National Council for Citizenship and Immigration and the Directorate for Citizenship and Immigration Control are responsible for monitoring the entry and residence of foreigners in the country, the registration of Ugandan citizens, issues pertaining to passports and travel documents, and border control (IOM, 2015).

Uganda's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

The Diaspora Department (within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) manages relations with the diaspora in other countries. The National Coordination Mechanism on Migration is a formal inter-ministerial coordination mechanism, established in 2015 and composed of government agencies, international organisations, civil society, and academia led by the Office of the Prime Minister (ibid). An important role in terms of displacement is addressed by the Minister for Disaster Preparedness and Refugee Management.

INTERNAL MIGRATION

INTERNAL MIGRATION

The most recent comprehensive data on internal migration in Uganda has been retrieved from the 2002 household survey conducted by Uganda’s Bureau of Statistics. According to the survey, there were 1,349,400 domestic migrants in 2002 (IOM, 2015). In total, 65.9% of these migrants were found in urban areas, suggesting migration is predominantly rural to urban (ibid). The number of female domestic migrants was higher than that of male domestic migrants in both urban and rural areas (ibid). Unlike in the past when women migrated in most instances to accompany their spouses, currently women migrate independently in search of job opportunities. Most of the domestic migrants were aged 15 to 29 years (603,600), followed by those 15 years or under (501,500) (ibid).

In this context, 56.5% said they were working, 39.1% were unemployed, and 4.4% were looking for work (ibid). According to a study by the University of Makerere (Kampala), insecurity has been a significant factor in determining migration to Northern Uganda, while in the central region, the reason for migration has often been economic (Nagikanda, 2013). The reasons for voluntary internal migration were mainly to seek employment and, for migrant women in particular, to relocate as a result of marriage and related social movements (IOM, 2015). However, according to Maastricht University (2017), not much has changed in terms of the pattern of internal migration in Uganda as revealed by the 2002 household survey. More recently, changing climatic conditions appear to be a potential key driver of internal migration in Uganda. Because of the intricate connections between livelihoods, the economy, and the environment, adverse climatic conditions have a direct negative impact on the lives of Ugandans. According to Rigaud and her fellow researchers (2021), the impact of climate change, if not guarded against, could see the movement of about 12 million people, that is 11% of the country’s population moving within the country by 2050 in search of economic opportunities or sources of livelihoods.

INTERNALLY DISPLACED, CONFLICT AND DISASTER

INTERNALLY DISPLACED, CONFLICT AND DISASTER

Before the agreement to the cessation of hostilities was signed between the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the government of Uganda in 2006, internal displacement was highly precipitated by conflict and violence. For example, when the conflict was at its peak in 2005, 1.84 million people were internally displaced across 11 districts in northern Uganda, living in 251 camps (UNHCR, 2012). However, the numbers have declined significantly in recent years, with displacement increasingly triggered by disasters.

Although conflict and violence continue to contribute to internal displacement in Uganda, it is less compared to pre-2006 levels before the signing of the cessation of hostilities agreement. Post the 2006 agreement, conflict/violence is mostly driven by land disputes as returnees displaced by the LRA conflict compete for limited resources. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (2025), over the past four years, displacement associated with conflict/violence has increased from 1,000 in 2020 and 1,600 in 2021 to 4,500 in 2020, and 4,800 by the end of 2023.

Currently, natural disasters such as hailstorms, floods, and landslides have replaced conflict/violence as the main driver of internal displacement in Uganda. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) (2025), between 2008 and 2023, there were 656,000 disaster-related displacements in Uganda. Most displacements between 2008 and 2023 were caused by floods (ibid). Floods continue to drive disaster-related displacement in Uganda beyond 2023. For example, according to local authorities, floods in November 2024 displaced more than 350 people in the Namutumba district (ibid). In a country like Uganda where its nationals heavily depend on agriculture as a source of living, any form of disaster directly harms their livelihood.

IMMIGRATION

IMMIGRATION

Over the past decade, the number of international migrants residing in Uganda has increased considerably. This increase can be ascribed to the highly receptive nature of Ugandans towards immigrants. For example, an Afro Barometer analysis posits that 73% of Ugandans have no problem living next door to immigrants (Afro Barometer, 2024). In 2010, the stock of international migrants in Uganda was 492,930 (1.5% of the Ugandan population) (UN DESA, 2019). In 2015, it increased to 851,175 (2.2% of the population) and, in 2019, it reached 1,734,166 (3.9% of the population) (ibid).

According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), Uganda’s international migration stock experienced a slight decrease from the 2019 data as it stood at 1.7 million (representing 3.8% of the total population). Uganda’s net migration rate has fluctuated over the last 30 years. According to Macrotrends (2023), between 2015 and 2021, Uganda experienced a positive net migration rate fluctuating between 0.588 and 2.875. As a member of the East African Community (EAC) bloc that advocates for the free movement of its citizens across national borders, Uganda remains an attractive destination for international migrants. However, in 2022 and 2023, Uganda experienced a negative net migration rate of -1.090 and -2.367 respectively (ibid). Most international migrants in Uganda come from neighbouring or nearby African countries. In 2019, the main countries of origin of international migrants in Uganda were South Sudan (1.1 million) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (approximately 320,000), with Rwanda, Sudan, and Burundi each contributing about 60,000 to 70,000 to the total international migrant stock (UN DESA, 2019).

FEMALE MIGRATION

FEMALE MIGRATION

According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), since 2000, the ratio of male to female international migrants has shifted such that there have been slightly more (0.4%) female than male international migrants, and the proportion has steadily increased since then. In 2010, 50.9% of the total number of international migrants were female (251,000), and in 2015, this was 51.1% (435,300) (ibid). It rose to 51.9% (892,600) in 2019 (ibid).

This pattern reflects the global pattern of migration where more females than males have been migrating recently. Some international migrant women and children in Uganda are particularly vulnerable and exposed to various forms of abuse, neglect, stigmatisation, malnutrition, and a high probability of being infected with communicable diseases (IOM, 2015). One of the drivers of the feminisation of international migration in Uganda is the increasing involvement of women in cross-border trading as more women within the region are stepping away from traditional household responsibilities to look for opportunities to support their households. This pattern of movement is eminent within the region as, according to Parshotam and Balongo (2020), within Africa, 70% of informal cross-border traders are women.

MINORS

MINORS

According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), in 2010, 41.1% (202,089) of the 492,900 immigrants residing in Uganda were children aged 19 years and younger. In 2015, 49.5% (421,344) of the 851,200 immigrants residing in the country were children, and in 2020, 57.5% (977,500) of the 1.7 million immigrants were children aged 19 years and younger (ibid). This represents a significant increase in the number of child immigrants living in the country between 2010 and 2020.

This growing pattern of child immigrants into Uganda corresponds with the growing pattern of child migration within the country. In Uganda, internal migration among children is common. For example, the IOM (2014) noted an increase in internal migration involving children, particularly from the Karamoja region to urban centres. The main motivation for migration to urban settings is to earn money following children’s actual or perceived responsibility to contribute to their households (ibid). The children typically live in extreme poverty and are highly vulnerable (ibid). Their reasons for migration are linked to the decreasing number of livestock in their region of origin and the general lack of livelihood opportunities, which makes these children unable to contribute to the family’s income (ibid).

Internal child migration in Uganda is circular in nature as children migrate to urban centres to earn a living in various ways, return home with their earnings, and eventually migrate again to earn more. Although the government has placed a ban on street children’s donations, the societal expectation that children should contribute to household income contributes to the large number of children migrating to urban areas, without or with the approval of their parents, to earn money through begging, various gimmicks, or theft (IOM, 2015). In essence, begging mitigates the absence of employment opportunities and serves as a major source of income for some households. Unfortunately, because children invoke sympathy, they are often used by their parents as a bargaining chip in the process of begging.

REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

According to the UNHCR (2023a), Uganda is one of the top five countries that host the largest number of refugees and asylum seekers in the world. By March 2023, Uganda hosted 1,532,168 refugees and asylum seekers (UNHCR, 2023b). By December 2024, the number of refugees and asylum seekers went up to 1,796,609 (UNHCR, 2024). Refugees and asylum seekers in most parts of the country feel welcome. According to Afro Barometer (2024), 64% of Ugandans welcome refugees and asylum seekers in their communities. The top five origin countries of refugees and asylum seekers in Uganda are South Sudan 54.3% (975,079), Democratic Republic of Congo 31.3% (561,880), Sudan 3.6% (65,535), Eritrea 3.3% (59,478), and Somalia 2.8% (50,832) (ibid). The refugees and asylum seekers are located in 13 districts, namely Madi Okollo and Terego (239,798), Adjumani (228,294), Isingiro (220,561), Yumbe (204,034), Kampala (157,444), Kikuube (144,726), Kiryandongo (137,838), Obongi (137,020), Kyegegwa (132,526), Kamwenge (100,187), Lamwo (86,195), and Koboko (6,276) (ibid).

Uganda does not have an encampment policy. The government, in collaboration with international organisations such as the UNHCR, established refugee settlements, where refugees are provided with a piece of land to build their own houses and engage in livelihoods. While most of the refugees in Uganda are in refugee settlements, others are in urban areas (self-settled refugees), especially in Kampala. There are 13 refugee settlements in Uganda: Adjumani, Bidibidi, Imvepi, Kiryandongo, Kyaka II, Kyangwali, Lobule, Nakivale, Oruchinga, Palabek, Palorinya, Rhino Camp, and Rwamwanja (UNHCR, 2021). The refugees in the urban areas are scattered among low-income informal settlements.

Various international organisations have applauded the refugee settlement model in Uganda as it gives refugees a sense of security and self-reliance and facilitates their integration process within their host communities (Wamara et al., 2021). However, refugees in Uganda face certain challenges. For example, while those in settlements are supported by the government and international organisations (food, health, education, and accommodation), their right to free movement is limited, which hampers their integration process. On the other hand, while self-settled refugees enjoy the right to free movement, which helps to facilitate their integration process, they do not enjoy any form of support from international organisations or the government. As a result, these self-settled refugees live in informal settlements with insufficient access to water, sanitation, and hygiene and they are vulnerable to harassment and forced eviction (Norwegian Refugee Council, 2021). Despite these challenges that refugees and asylum seekers need to cope with, Uganda is one of the countries on the continent that seeks to welcome, protect, promote, and integrate migrants. Uganda has become a referral point for many countries because of its progressive refugee hosting policy.

EMIGRATION

EMIGRATION

The most important attraction and push factor for Ugandan migration around and outside their country is employment, as economic opportunities in Uganda are limited (IOM, 2015). According to Afro Barometer (2019), one in three Ugandans has considered moving to another country, with a higher proportion of these aspirants being youth and most well educated. In 2010, Uganda had an estimated 731,800 emigrants abroad which rose to 786,200 in 2015 and dropped slightly to 781,400 in 2020 (Migration Data Portal, 2021). In 2013, the main destination countries of Ugandan emigrants were Kenya (271,149), South Sudan (120,808), Rwanda (106,501) the United Kingdom (64,223), and the United States of America (19,453) (United Nations, 2015).

It is important to note that an increasing number of Ugandans, particularly domestic workers, are migrating to the Middle East, growing from an average of 24,086 between 2016 and 2021 to 84,966 in 2022 (Zawya, 2023). The signing of a bilateral agreement between the government of Uganda and Saudi Arabia has made the Middle East a preferred destination for many Ugandans. For example, of the 84,960 migrant workers from Uganda in 2022, 77,914 went to Saudi Arabia, of which 55,643 mainly worked at housemaids (ibid). The bilateral agreement between the two countries (Uganda and Saudi Arabia) protects workers from exploitation.

LABOUR MIGRATION

LABOUR MIGRATION

With the diversification of East African economies such as that of Uganda, Kenya, and Rwanda, the demand for workers has increased (for example, in the services industry), drawing migrant workers from other East African countries (IOM, 2020; WMR, 2020). The East African Common Market Protocol, which allows for the free movement of labour, has facilitated labour migration within the East African sub-region (ibid). Several countries have ratified this protocol, and some have already abolished work permits for East African citizens, for example, Kenya, Rwanda and recently, in 2015, Uganda. This makes it easier for people to work across the sub-region (The East African, 2015). At the national level, Uganda’s Employment Act provides equal opportunities for national workers and immigrant workers who are legally residing in the country (IOM, 2018a). As indicated above (see the Emigration section), ratifying the protocol that allows people to move freely and work within the relevant countries also protects migrants from exploitation and bad labour practices in Uganda.

HUMAN TRAFFICKING

HUMAN TRAFFICKING

Uganda is ranked a Tier 2 country in the Trafficking in Person (2023) TIP Report as the government of Uganda does not meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking although it has made some significant efforts in recent years. However, corruption among some law enforcement officials negatively impacts the government's fight against human trafficking in the country. In 2023, the government prosecuted 12 government officials involved in potential trafficking crimes (US Department of State, 2024).

Uganda remains a source, transit, and destination country for children and women subjected to forced labour and sex trafficking. Because of poverty and unemployment, traffickers prey on the vulnerabilities of children and women who are in desperate search of opportunities. Traffickers exploit women and children both in Uganda and abroad. Through local radio stations and social media, traffickers fraudulently advertise job opportunities in urban areas like Kampala to lure children into their trap (ibid). Children from the Karamoja region (the poorest region in Uganda) are particularly vulnerable. For example, an estimated 2,057,00 children are involved in child labour and 700 to 18,000 children are victims of sex trafficking in Uganda (Klabbers et al., 2023).

Abroad, some employment agencies exploit Ugandan women and children, particularly in the Middle East, as indicated by an unnamed NGO which mentioned that 89% of Ugandans working in the Middle East experience conditions indicative of forced labour such as excessive working hours and passport confiscation (US Department of State, 2023). Such experiences indicate that the bilateral agreement on labour migration signed between the two countries (see section on Emigration) has not been adequately implemented. In 2023, the Ugandan government reported that it was investigating 1,006 incidents of human trafficking, and initiated prosecution against 589 alleged traffickers (373 for sex trafficking, 81 for labour trafficking, 32 for sex and labour trafficking, and 103 for unspecified forms of trafficking), and continued prosecution of 1,041 alleged traffickers from 2022 (US Department of State, 2024). In 2023, the government obtained convictions for 130 traffickers (68 for sex trafficking, 31 for forced labour, and 31 for unspecified forms of trafficking) (ibid). The involvement of government officials in the facilitation of trafficking in Uganda highlights some of the challenges associated with the fight against human trafficking. Trafficking therefore remains a crisis in the country as those responsible for protecting victims and ensuring the successful prosecution of traffickers are themselves often traffickers.

REMITTANCES, RETURNS AND RETURNEES

REMITTANCES, RETURNS AND RETURNEES

The remittance flow in Uganda is one of the sources of the country’s foreign earnings. According to the World Bank (2023), Uganda has experienced a steady increase in remittance flow into the country since 2015. In 2015, remittance flow stood at $902,157,540 (2.8% of GDP). In 2017, it increased to 1.17 billion (3.8% of GDP), and in 2018, it went up to 1.42 billion (4% of GDP) (ibid). However, with the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, which was characterised by a slowdown in economic activities all over the world, remittance flow to Uganda dropped to 1.06 billion in 2020 and slightly increased to 1.08 billion in 2021 (2.7% of GDP) (ibid). Despite the decline, remittance flow still provides crucial support to many households in Uganda, safeguarding health care, food security, savings, and investment opportunities. Other factors that have negatively impacted the remittance flow to Uganda include the high cost of sending money, which stood at 8.7%, which is more than double the 3% target of the Sustainable Development Goals recommendation (International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2021). In addition to contributing to household consumption, remittance flow in Uganda also contributes to GDP growth leveraging more jobs within the economy.

The government of Uganda, political movements, and international organisations play a key role in assisting Ugandans abroad who voluntarily want to return home. For example, the International Organization for Migration assisted more than 100 vulnerable Ugandan women in Saudi Arabia during the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic which slowed down economic activities and placed travel restrictions on migrants (IOM, 2020). Still in the Middle East, the government of Uganda assisted 68 Ugandans stranded in Dubai, and the main opposition party, the National Unity Platform (NUP), indicated through one of their officials that the party has assisted 42 Ugandans to return home from Dubai (Monitor, 2022). However, some migrants return on their own without any assistance from the government, political movements, or non-governmental organisations. Before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, returnees with secondary school and higher qualifications managed to reintegrate economically while those with lesser qualifications did not enjoy the same advantage (Thomas, 2008). After the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, academic qualifications did not benefit returnees as they were all labelled, stereotyped, and discriminated against because they were seen as carriers of the coronavirus (Lubega & Ekol, 2020).

INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATION

The most important international organisations dealing with migration-related issues in Uganda are the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and the International Labour Organization (ILO). The IOM focuses on migrant health, refugee resettlement, humanitarian assistance, migration for work reasons, migration policy and research, and it also assists the government with border management. The UNHCR guides and coordinates international actions to protect refugees while the ILO develops programmes to promote decent work for all women and men including migrants. Other migration-related United Nations agencies in Uganda include the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) which provides support to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for capacity building, focusing on the management and policy of the diaspora. The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) focuses on the migration of children, especially from Karamoja to various urban areas and helps families keep their children in school. The Norwegian Refugee Council, Justice Defenders, International Refugee Rights Initiative (IRRI), and War Child International assist refugees and migrants with life-saving and long-term support.

Afro Barometer. 2019. Young and educated Ugandans are most likely to consider emigration. Retrieved from: https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ab_r7_dispatchno307_young_educated_ugandans_most_likely_to_consider_emigration.pdf

Afro Barometer. 2024. Ugandans support cross-border mobility for East Africans, but want fewer immigrants. Retrieved from: https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/AD831-Ugandans-support-cross-border-mobility-but-want-fewer-immigrants-Afrobarometer-5aug24.pdf

Akello, V. 2009. UNHCR | Uganda’s progressive Refugee Act becomes operational. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/news/latest/2009/6/4a3f9e076/ugandas-progressive-refugee-act-becomes-operational.html

CIA World Factbook. 2024. Uganda. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/uganda/

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2022. Country profile: Uganda. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/uganda

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2025. Country profile: Uganda. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/uganda/

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). 2021. Uganda remittances decline but still are a lifeline for rural people. Retrieved from: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/latest/-/ugandan-remittances-decline-but-still-are-a-lifeline-for-rural-people

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2014. Child migration from Karamoja. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/uganda/child-migration-karamoja

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2015. Migration in Uganda: A rapid country profile 2013. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mp_uganda_25feb2015_web.pdf.

Klabbers, R.E., Hughes, A., Dank, M., O’Laughlin, K.N., Rogers, M. & Stoklosa, H. 2023. Human trafficking risk factors, health impacts, and opportunities for intervention in Uganda: A qualitative analysis. Global Health Research and Policy, 8(52). Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-023-00332-z

Lubega, M. & Ekol, J.E. 2020. Preparing communities to receive persons recently suspected or diagnosed with COVID-19. Pan African Medical Journal, 5(35)(Suppl 2):21. Retrieved from: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23202

Macrotrends. 2023. Uganda net migration rate 1950 – 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/UGA/uganda/net-migration

Migration Data Portal. 2021. Uganda. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/

Monitor. 2022. Government repatriates 156 Ugandans from Dubai. Retrieved from: https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/government-repatriates-156-ugandans-from-dubai-3994116

Mosel, I., Leach, A. & Hargrave, K. 2020. ODI Global | Public narratives and attitudes towards refugees and other migrants: Ugandan country profile. Retrieved from: https://odi.org/en/publications/public-narratives-and-attitudes-towards-refugees-and-other-migrants-uganda-country-profile/

Nagikanda, A. 2013. Factors explaining the reasons for internal migration in Uganda (Master’s Thesis). Kampala, Uganda: Makerere University.

Norwegian Refugee Council. 2021. Local integration of urban refugees in Uganda. NRC’s community-based and integrated programming approach. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/uganda/local-integration-urban-refugees-uganda-nrcs-community-based-and-integrated

Parshotam, A. & Balongo, S. 2020. Women traders in East Africa: The case study of the Busia One Stop Border Post. Retrieved from: https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Occasional-Paper-305-Parshotam-Balongo.pdf

Rigaud, K.K., De Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Casals Fernandez, A.T. & Adamo, S. 2021. Groundswell Africa: A deep dive into internal climate migration in Uganda. World Bank, Washington, DC. Retrieved from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36447

The East African. 2015. Uganda joins Kenya, Rwanda in abolishing work permits for professionals. Retrieved from: https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/uganda-joins-kenya-rwanda-in-abolishing-work-permits-for-professionals-1337882

Thomas, A. 2008. Returning migration in Africa and the relationship between educational attainment and labour market success. Evidence from Uganda. The International Migration Review, 42(3):652-674. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27645270

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2019. International stock of migrants. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp

United Nations (UN). 2015. Migration profiles: Uganda. Retrieved from: https://esa.un.org/miggmgprofiles/indicators/files/Uganda.pdf

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2021. Uganda. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/86497.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023a. Refugee data finder. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023b. Uganda comprehensive refugee response portal. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/uga

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Uganda comprehensive refugee response portal. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/uga

US Department of State. 2022. Trafficking in Persons Report: Uganda. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/uganda/

US Department of State. 2024. Trafficking in Persons Report: Uganda. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/uganda/

Wamara, C.K., Muchacha, M., Ogwok, B. & Dudzai, C. 2021. Refugee integration and globalization: Uganda and Zimbabwean perspectives. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 7: 168-177. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41134-021-00189-7

World Bank. 2023. Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Uganda. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=UG

World Bank. 2023. Personal remittances, received (current US$) – Uganda. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT?locations=UG

Zawya. 2023. Uganda earns $600 million annually from migrant workers in Middle East. Retrieved from: https://www.zawya.com/en/economy/africa/uganda-earns-600mln-annually-from-migrant-workers-in-middle-east-xrcdgwbd