INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

South Africa is a diverse nation with a complex history, that has experienced significant migration patterns influenced by economic, political, and social factors. The country’s migration policies, including the Refugees Act and Immigration Act, aim to regulate and protect migrants while addressing concerns about irregular migration and its impact on society. Despite efforts to regularize migrants, special permits and programs have recently expired, leaving many in precarious situations. South Africa’s Department of Home Affairs manages refugee and migrant affairs, including identification, documentation, and border control. Internal migration in South Africa is predominantly rural-urban, driven by labor-related factors, with an increasing feminization of this trend. South Africa hosts a significant number of refugees and asylum seekers, with the Department of Home Affairs responsible for their status determination and protection under the Refugees Act of 1998. South Africa has experienced a significant increase in refugee and asylum seeker populations, primarily from neighboring countries. The country has also seen a substantial emigration of highly skilled workers, particularly to Australia. Despite legal frameworks to combat human trafficking, the issue remains prevalent, with victims exploited in various sectors, including domestic service, agriculture, and sex trafficking.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

International migration into South Africa is an old phenomenon. As a white settler colony in the 19th century – South Africa attracted thousands of European migrants who permanently migrated to South Africa during colonial rule (Peberdy, 1997). The opening of the diamond fields in Kimberly and Witwatersrand precipitated a huge demand for unskilled and cheap labour readily available in the neighbouring SADC countries. According to Van der Horst (1971), by 1899, there were about 97,000 foreign mineworkers in South Africa, mainly from other African countries. According to Wentzel and Tlabela (2006), before 1963 - when the first migratory law came into effect, there was no statutory differentiation between workers from other African countries and indigenous South Africans. However, the apartheid migratory policies in South Africa had four distinctive characteristics; racist policy and legislation, the exploitation of migrant labour from neighbouring countries, tough enforcement legislation, and the repudiation of the international refugee convention.

The ushering of a new political dispensation in 1994, whose doctrine was grounded on building an inclusive society, motivated a new wave of migration into the country. Given its advanced economy and relative political stability, South Africa remains one of the migration hubs in Africa - attracting migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees from within and outside Southern Africa. In the opinion of the Migration Policy Institute (2021), the end of the apartheid rule created new prospects for internal and international migration and a new inducement for movement. Other key factors that influence migration into South Africa from other parts of Africa include globalization, economic, political, and social crisis. It is important to note that after the demise of apartheid and its racial segregation policies, South Africa, led by the ANC government, still retained the old immigration policy (Alien Control Act of 1991), though with some changes like the cancellation of the Population Registration Act, pass laws and the Bantustan Act, and also the opening of the country to other African migrants as enshrined in the Refugee Act 130 of 1998. In the opinion of Wentzel and Tlabela (2006), three streams of movement from Africa to South Africa can be identified from the colonial to post-colonial era: contract migration, other categories of voluntary migration, and refugee migration.

Nelson Mandela meets the United States Boxers. Source: UN Photo / Milton Grant

MIGRATION POLICIES

MIGRATION POLICIES

The primary legislation governing refugees and asylum seekers is the 1998 Refugees Act (Act 130 of 1998). It extends the protection of forced-migrants. It applies a rights-based approach to asylum seekers that rejects camps and allows asylum seekers to move freely. It grants the right to work and study to refugees and asylum seekers and deliberately refuses to make a distinction between asylum seekers and refugees in many respects. The Act additionally defines who is a refugee and sets out the refugee status determination process, and it sets out and affirms the principle of non-refoulement and the non-penalization of irregular entry or presence of anyone in South Africa seeking asylum. The 2008, 2011, and 2017 Refugees Amendment Acts; all amended the Refugees Act 130 of 1998. The amendments were signed along with corresponding requisite regulations in 2019 and came into force in January 2020.

The 2017 Refugees Amendment Act is the most extensive of the amendments that add extensively to provisions on the exclusion of refugee status, excludes asylum seekers from refugee status if they haven't reported to a Refugee Reception Office within five days of entering the country, and limits the right to work for asylum seekers to those who are unable to support themselves and their families after four months and those who are not supported by an NGO or UNHCR. Asylum-seekers must also be able to provide a letter of employment within six months of being granted the right to work. The amendment extends the time limit before refugees may request permanent residence from 5 to 10 years. It also provides for a fine or prison sentence (up to five years) for persons in possession of an expired asylum-seekers visa allowing for asylum applications to lapse and the removal of asylum seeker's registration in the status determination process.

Additionally, international migrants are governed by the Immigration Act that refines migration policy to ensure various forms of migration including visits and sojourns, study, and the migration of skilled labour. The Act also provides for identification and deportation processes. It implements different categories of work permits to facilitate access to foreign skills for South African employers primarily on a temporary basis. The Act also reinforces temporality, control, and deterrence of migration. In general, it strengthens border surveillance and immigration law enforcement, read with the South African Border Management Authority Act 2 of 2020, to curb irregular migration and reduce associated "pull factors". In 2004 the Immigration Amendment Act was passed that reinforced the restrictive nature of the original Immigration Act and included an extension in the powers of the Minister and Director-General of Home Affairs, reduced the number of permits available, and adjusted the work permit policy to apply only to persons in a particular "occupation or class". The 2007 Immigration Amendment Act brings about changes in favour of cross-border merchants, particularly women, and relaxed the obligation for African students to pay repatriation fees.

.png)

Timeline of Migration Policies in South Africa. Source: SIHMA

Government dispensation projects and permits were starting with the 2010: Zimbabwean Dispensation Project followed by the Zimbabwean Special Permits, the Angola Special Permits, and the Lesotho Special Permit process, aimed at regularising and documenting generally low-skilled international migrants from SADC countries with documentation that enabled permit holders to work or study in South Africa without the complexity of the Immigration Act visa options. Some of these special permits have already expired, for example, the Angola and Lesotho Special Permits that expired in 2021 and 2019 respectively and the Zimbabwean Special Permit will also expire by the end of 2023 – putting permit holders in a very precarious position.

The majority of the provisions in the South African Constitution relate to everyone within the country including international migrants. The Births and Deaths Registration Act and the Citizenship Act also relate to people on the move. South Africa is also a party to several international instruments that relate to refugees and migrants. This includes the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 protocol and the 1969 OAU Refugee Convention. South Africa has signed the 2005 South African Development Community (SADC) Protocol on the Facilitation of Movement of Persons which allows visa-free travel between SADC States for up to 90 days and aims to promote a liberal policy of permanent and temporary residence and a work permit policy between SADC States, but the protocol is yet to come into force due to the limited number of ratifications. South Africa is not a party to the Statelessness Conventions of 1954 and 1961, nor is it a party to the 2009 Kampala Convention on IDPs. To prevent and combat the trafficking in persons, there is the 2013 Prevention and Combating of Trafficking in Persons (PACOTIP) - although the regulations for the Act’s immigration provisions are yet to be promulgated.

GOVERNMENTAL INSTITUTIONS

GOVERNMENTAL INSTITUTIONS

The Department of Home Affairs is the primary government Ministry concerning refugees and migrants and is responsible for the identification and documentation, grants refugee status, and deals with border control and migration matters. There are several other relevant government departments including the Department of Social Development, the Department of Basic Education, the Department of Health, and the Department of Labour. The Department of Home Affairs contains various directorates including the Immigration Inspectorate that works with the South African Police Service and the Asylum Seeker Management. The Director-General of Home Affairs determines the need and location of Home Affairs Refugee Status Determination offices in consultation with the Standing Committee for Refugee Affairs. Refugee Status Determination is managed by Refugee Status Determination Officers (RSDOs) and RSDO’s rejection decisions which are appealed go before the Refugee Appeal Board or are subject to review by the Standing Committee for Refugee Affairs.

- Department of Home Affairs website here

- Department of Social Development website here

- Department of Basic Education website here

- Department of Health website here

- Department of Labour website here

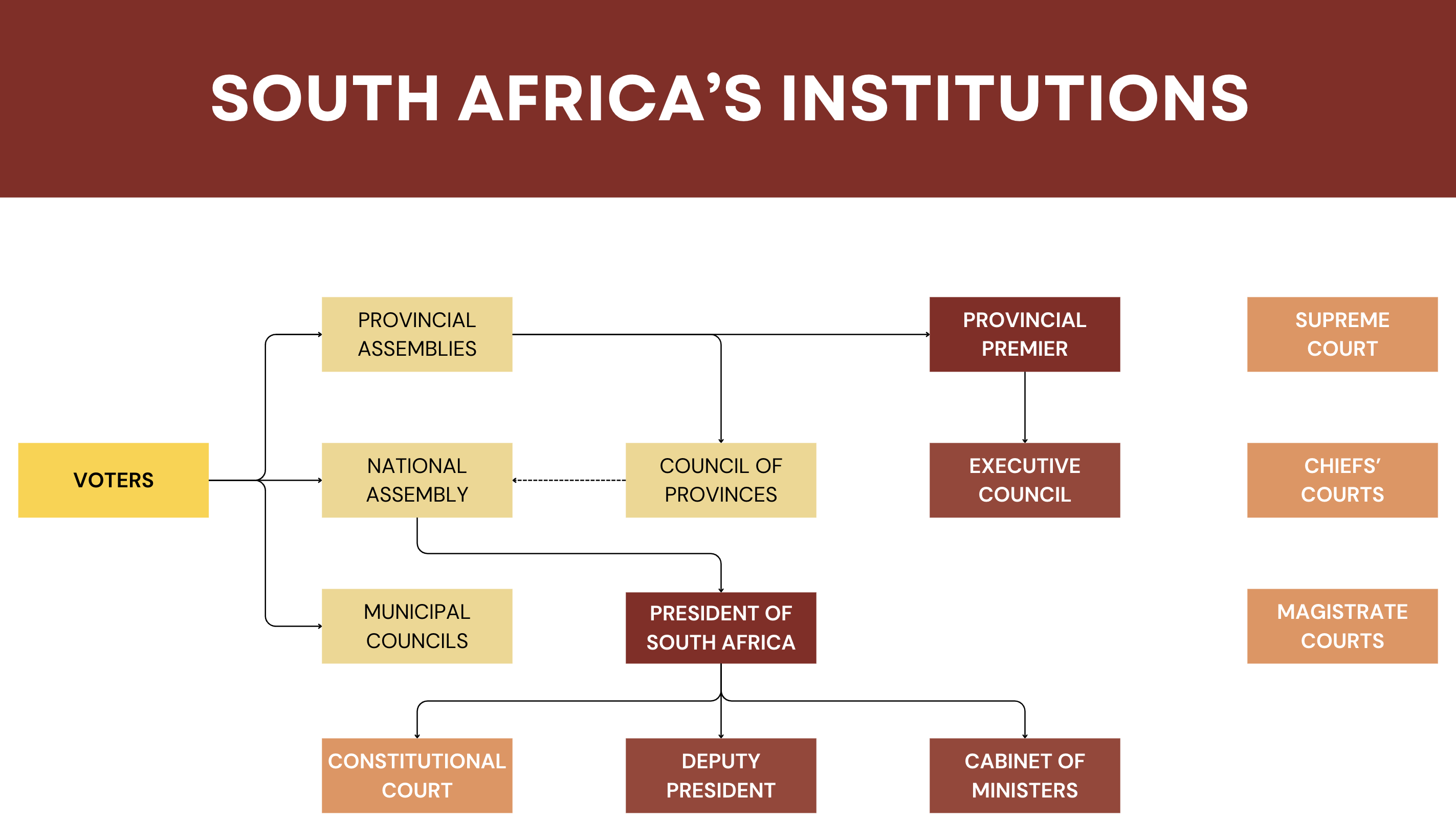

South Africa's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

INTERNAL MIGRATION

INTERNAL MIGRATION

Internal migration within the context of South Africa predominantly refers to rural-urban migration. During the apartheid era, due to the restrictive apartheid legislation, South Africa experienced circular internal migration as recruited black South African men moved back and forth between their permanent rural homes and the urban mining areas as they were restricted from permanently settling in the urban areas where they worked. In post-apartheid South Africa, permanent relocation from rural areas to urban areas is exceeding cross-border migration. For example, according to Statistics South Africa (2011), 5% of the population has experienced some form of internal migration compared to 1% having immigrated from outside the country (Ginsburg et al., 2021).

Similar to the apartheid era, internal migration in contemporary South Africa is largely labour-related. However, unlike the apartheid era with its male-dominated internal migration patterns, there has recently been an increase in female-dominated internal migration patterns. According to the Population Census (2011), age, gender, and education are key individual-level predictors of internal migration, and such migration is intricately linked to employment and job-seeking motives. This means that municipalities with high unemployment rates typically experience high levels of out-migration. A quarter of all internal migration occurs between Gauteng and Limpopo and Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal – with Gauteng having 45% of the total internal migration population (ibid).

Interestingly, there is also rural-rural migration in South Africa. High levels of unemployment and scarcity of jobs in the cities are some of the drivers of this type of migration. People are now migrating to peri-urban settlements (smaller towns) where they can get better access to government services and where the cost of living is low compared to urban settlements. People also migrate from one rural area to another – especially where there are employment opportunities (Atkinson, 2014). An example: Migration from rural areas to the Mpumalanga farms and game farms is increasing because of growing tourism in the area. Lack of opportunities in urban settlements and the growing cost of living have also seen urban-rural migration though at a small scale.

INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS, CONFLICT AND DISASTERS

INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS, CONFLICT AND DISASTERS

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (2023), 211,000 people have been displaced in South Africa because of conflict/violence and disaster. Recently, disaster-related displacement has contributed enormously to the stock of internal displacement in the country.

Historically, South Africa has been characterised by forced removals as a result of the apartheid policies driven by the desire of the government to provide separate development for different races – Whites, Africans, Indians, and Coloureds – through the creation of Bantustan Homelands. The demise of apartheid, the subsequent repealing of laws that formed the basis of forced removals (like the Group Areas Act and the Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act), and the new democratic-led ANC government’s promise of providing a better life for every South African created a beacon of hope to all disadvantaged South Africans. However, things have not materialised so well for most disadvantaged South Africans living in informal settlements or “shacks” as they are still a subject of forced removals in the “new” South Africa. In some cases, these removals are reminiscent of apartheid forms of forced removal (The Guardian, 2022). Furthermore, in December 2020, a land dispute in Masiphumelele on the Cape Peninsula triggered the displacement of 5,000 people (IDMC, 2020).

211,000 Internally Displaced Persons in South Africa (2023)

Natural disasters such as floods, hailstorms, tornadoes, and wildfires have also contributed to internal displacement in South Africa. For example, flooding in areas of Ivory Park northeast of Johannesburg destroyed homes and left at least 187 people homeless (Floodlist, 2022). In April 2022, the province of KwaZulu-Natal experienced floods that killed 443 people and displaced more than 40,000 people (Reliefweb, 2022). Also, according to Independent Online (IOL) (2023), floods displaced 151 people in Durban, with Phoenix, Inanda, Ntuzuma, Kwasmashu, Pinetown, Folweni, Umzumbe, Umdoni, and Umuziwabantu as the hardest hit areas. In June 2023, floods displaced more than 1,000 residents in Rawsonville in the Western Cape (News24, 2023). In October 2024, severe thunderstorms displaced 38,785 people in four provinces (Mpumalanga, Eastern Cape, Free State, and Limpopo) (IFRC, 2024).

Although disaster-related displacements constitute the main driver of displacement in the country, the socio-economic conditions of South Africans make conflict or violence an essential element in the displacement index of the country.

IMMIGRATION

IMMIGRATION

As one of the economic powerhouses in the continent, South Africa remains an attractive destination for immigrants. In 2001, the international migrant stock in South Africa was estimated at 1,025,074 (610,374 male and 414,700) (Statistics South Africa, 2023). In 2011, it was 2,18,408 (1,314,633 males and 869,775 females) (ibid). In 2022, it was estimated to be 2,418,206 (1,397,983 males and 1,020,223 females) (ibid). This reflects a steady increase from 2001 to 2022.

Slightly more than 100,000 of these immigrants are from the United Kingdom while all other immigrants come from African countries, specifically from other SADC countries. Mozambique has more than 700,000 immigrants in South Africa while Zimbabwe has almost 400,000 immigrants, Lesotho has about 350,000, and Namibia has about 200,000 immigrants (UN DESA, 2019). The recent increase can be ascribed to South Africa's comparatively more industrialised economy, more stable democratic institutions, and status as a middle-income country. However, it is important to note that the statistics may not be a true reflection of the number of immigrants in the country because of restrictive immigration policies and the reluctance of the Department of Home Affairs to issue legal documents to immigrants (Amit & Kriger, 2014). As a result, some immigrants, especially from the continent, enter the country through irregular channels.

FEMALE MIGRATION

FEMALE MIGRATION

In 2010, 42.2% (888,216) of the international migrant stock were women. In 2015, the female international migrant stock stood at 44.4% (1,694,614). In 2019, it was estimated to be 44.4% (1,875,588) of the international migrant stock (UN DESA, 2019). Although women's participation in the labour force in South Africa remains lower than that of men – 54.3% and 64.9% respectively – international female migration into the country is on the rise (Statistics SA, 2022). The steady increase of female migrants into South Africa, especially from other parts of Africa, can partly be ascribed to many of the migrant women’s perception of the country’s economy as growing and vibrant with opportunities not available in their country of origin (Democracy Development Program, 2022). Upon arrival, many migrant women are involved in the unregulated informal economy which makes them vulnerable. According to the Institute for Security Studies (2019), because of this vulnerability, women migrants are at heightened risk of sexual violence, exploitation, forced labour, abuse, and health issues. The Institute further stated that migrant women in South Africa face triple discrimination as a result of xenophobia, racism, and misogyny.

MINORS

MINORS

Within the SADC region, factors such as poverty, violence, education, and the death of a caregiver account for child migration (UNICEF, 2024). In this context, South Africa represents a country of hope and opportunities for thousands of these migrant children. According to a UNICEF report, in 2024, there were more than 642,000 migrant or displaced children in South Africa, making it the country on the continent with the largest child migrant population.

This mixed movement includes unaccompanied and separated minors, smuggled migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and victims of human trafficking. Within the context of South Africa, the care and protection of unaccompanied and separated migrant children are determined by the courts, and they are typically placed in Child and Youth Care Centres (CYCC) or temporary community-based foster care. The legal framework in the SADC region is guided by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCHR) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC) to which South Africa is a party. Based on this framework, the state must act in the best interest of the child. Yet, the implementation of this framework leaves much to be desired as migrant children in the country face challenges such as the absence of documentation which prevents them from accessing services such as child support grants. Child migrants are also subjected to detention which makes them vulnerable to the violation of their human rights and deprives them of education, healthcare services, adequate food, clean water, and proper housing (Gadisa et al., 2020). Access to documentation remains one of the key challenges for child migrants as access to documentation translates into access to services within the country.

642,000 Migrant Minors in South Africa (2020)

REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

Refugees and Asylum seekers in South Africa are protected in terms of the Refugees Act of 1998 and accompanying regulations and in terms of extensive amendments to the Act and regulations that came into force in January 2020 (Refugee Act 130 of 1998 & Refugee Amendment Act 11 0f 2017, and additionally the 2011 and 2008 amendments). Refugee status determination is done by the South African Department of Home Affairs and consists of two to five stages including potential reviews and appeals. Refugees and asylum seekers have freedom of movement in South Africa and generally have the right to seek employment or self-employment although the aforementioned amendments limit certain categories of asylum seekers’ right to work (Refugee Amendment Act 11 0f 2017).

The refugee population in South Africa gradually increased from 6,800 in 1997 to 66,000 in 2013 and then rose fairly substantially to 112,000 and 121,600 in 2014 and 2015 respectively (Migration Data Portal, 2021). Since 2015, the refugee population dropped to 91,000 in 2016 and stabilised at about 89,000 each year from 2017 until 2019 (Ibid). Refugees in South Africa are primarily from Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo Brazzaville, Ethiopia, Burundi, and Zimbabwe. There is a similar trend with asylum seekers, with 463.9 thousand asylum seekers in 2014 and then a substantial rise and peak of 1.1 million in 2015 and thereafter plummeting to 218.3 thousand in 2016 and gradually dropping to 188.3 thousand in 2019 (Migration Data Portal, 2021). As of 2023, the refugee and asylum seeker population stood at 250,250 (UNHCR, 2023). Refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa come predominantly from Burundi, the Democratic Republic of South Africa, Rwanda, South Sudan, Somalia, and Zimbabwe (Ibid)

Asylum applications are made by a predominantly young asylum population with 71% of asylum applicants aged 19 to 35 and 17% being minors aged 0 to 18 years (Auditor-General Report, 2019). The number of asylum applications being processed plummeted over eight years from 223,324 in 2009 to 24,174 in 2017 (Ibid). The majority of asylum applications in the refugee determination process in 2017 were Ethiopian (26%), followed by DRC (17%), Bangladesh (14%), Zimbabwe (10%), and Pakistan and Nigeria (each at approximately 5%) with the balance from other countries (Ibid). There is a substantial backlog of asylum cases escalated to the internal government appeal or review authority and remain undecided, amounting to 188,296 active cases by 2019 (German Network for Forced Migration Studies, 2020). The study also indicates that the Refugee Appeals Board is working on a backlog that will take 68 years to complete (Ibid). The slow pace in the finalisation of claims means that asylum seekers will continue to be in limbo.

EMIGRATION

EMIGRATION

The total number of emigrants from South Africa in mid-2020 was 914.9 thousand (Migration Data Portal, 2021). In the post-apartheid period, increasing numbers of highly skilled white workers emigrated, citing disillusionment with the government, load shedding, high unemployment, poverty, crime, poor services, and a reduced quality of life (CIA World Factbook, 2022). The 2002 Immigration Act and later amendments, were intended to facilitate the temporary migration of skilled foreign labour to fill labour shortages, but instead, the legislation continues to create regulatory obstacles (Ibid). The 2017 White Paper on International Migration from the Department of Home Affairs stated that South Africa loses a significant percentage of its skilled workforce every year. An estimated 520.000 South Africans emigrated between 1989 and 2003, with the numbers increasing by approximately 9% annually (Department of Home Affairs, 2017). Around 120.000 of those emigrants had professional qualifications that represent about 7% of the total stock of professionals employed in South Africa and is more than eight times the number of professionals in the same period immigrating to South Africa (Ibid). Although the education system has improved and the brain drain has slowed in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, South Africa continues to face skills shortages in several key sectors, such as health care and technology (Ibid). The South Africa-Australia migration corridor is among the top 10 migration corridors involving Oceania countries with the migration of almost a quarter of a million South Africans to Australia.

914,900 South African Emigrants (2020)

LABOUR MIGRATION

LABOUR MIGRATION

Like any other aspect of movement regulated during the apartheid era, labour migration was no exception. Labour migration during this era was circular - with black migrant labourers oscillating between their temporary work places and their permanent homes (Posel, 2006). The migrant labour system during the apartheid era was designed to feed the growing demand for cheap labour in the cities and mines (Vosloo, 2022). While the nature of this movement has changed within the country - with more people migrating from the rural areas together with their families to permanently reside in the urban areas where they are employed, little has changed with international migrants as they still consider themselves temporary migrants (Posel, 2006). According to the African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS) (2020), in 2017, there were an estimated two million international migrants of working age (15-65) in South Africa - constituting 5.3% of the labour force - more likely to be employed in precarious work and or the informal economy. The study further reveals that 27.1% of international migrants work in the informal sector, and 12.4% work in private households as gardens, nannies, and domestic workers (Ibid). The statistics therefore indicate a steady increase in the number of migrant labourers in South Africa. It is important to note that a cross-section of the immigrant labour force is more likely to be employed in precarious work or the informal economy where they are self-employed (OECD/ILO, 2018). The above analysis debunks the classical labour theories of migration as a reasonable percentage of labour migrants do not come into the country in search of jobs but in search of opportunities to create jobs for themselves.

It is important to note that through its regional economic formation – SADC, there is an express intent to facilitate the movement of migrant labour within the region. For example, Article 2.1 (C) promotes “labour policies, practices, and measures, which facilitate labour mobility, remove distortion in labour markets and enhance industrial harmony and increase productivity, in SADC member states” (Charter of Fundamental Social Rights in SADC, 2003:3). Paradoxically, the establishment of the framework is met with increased border securitization and border management approaches that do not only delay but prevent the free movement of people (Tevera, 2020).

HUMAN TRAFFICKING

HUMAN TRAFFICKING

For the past five years, South Africa has been classified as a country of origin, transit, and destination for trafficking. It entails that victims are trafficked from South Africa and moved through the country to other areas for exploitation and that foreign victims are brought to the country as their final destination. Trafficking is not generally reported to the police because victims fear retaliation, which means that updated statistics on the extent of human trafficking are not available. South Africa is also a Tier 2 country as the government is making significant efforts in some respects but does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking as espoused by the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA) (US Department of State, 2023).

During the reporting year, 2024, the government identified and referred 291 trafficking victims to care (67 labour trafficking victims, 26 sex trafficking victims, and 198 victims of unspecified forms of trafficking) (US Department of State, 2024). On their part, through transit monitoring, NGOs identified 52 trafficking victims and 383 potential victims (US Department of State, 2022). Trafficked victims were provided with temporary emergency shelter, food assistance, interpreters, specialised medical care, psycho-social support, and transportation (US Department of State, 2024). The government investigated 156 trafficking cases and prosecuted 123 suspects (28 for sex trafficking, 13 for forced labour, and 82 for unspecified trafficking) and continued with the prosecution of 109 suspects from 2023 (ibid). The government obtained convictions against 12 sex traffickers (ibid).

Traffickers typically recruit victims from poor countries and rural or poor areas within South Africa to urban centres like Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban, and Bloemfontein where the traffickers force their victims to work in the domestic service or agricultural sectors, illegal mining, criminal activities, and sex trafficking (US Department of State, 2023). Some of the traffickers use traditional spiritual practices to coerce their victims (ibid). Traffickers also exploit foreign males aboard fishing vessels in South Africa’s territorial waters and young men from neighbouring countries who migrate to South Africa for farm work (ibid). Some of the victims are then arrested and deported as undocumented immigrants (ibid). The US Department of State (2020) highlighted that traffickers subject Pakistanis and Bangladeshis to forced labour through debt-based coercion in businesses owned by their co-nationals (ibid).

One of the key challenges of the South African government in combating trafficking is the complicity of some of the government officials in trafficking activities. For example, in 2021, three police officers were charged with extorting potential trafficking victims while two National Prosecuting Authority officials were charged with protecting a high-profile public figure for an alleged child sex trafficking offence (ibid).

Bello and Olutola (2022) argued that despite the existence of a good legal framework to fight human trafficking in South Africa, these measures have not significantly reduced the rate of human trafficking. This legal framework is underpinned by the Prevention and Combating of Trafficking in Persons (PACOTIP) Act of 2013, aimed at criminalising trafficking, strengthening law enforcement capacity to combat human trafficking, and deterring criminals from engaging in it. The scourge of human trafficking persists in South Africa mainly because of inadequate protection for migrant labour, corrupt law enforcement officials, and poverty.

REMITTANCES, RETURNS AND RETURNEES

REMITTANCES, RETURNS AND RETURNEES

According to the World Bank (2022a), South Africa received its highest remittance payment in 2011, which amounted to $1.16 billion. Since then, it has experienced a sharp decline to $755,434,049 in 2016. From 2018 to 2022, remittance flow to South Africa fluctuated between $929,043,381 and $810,881,604 (ibid). From 2000 to 2022, remittances in South Africa constituted less than 3% of GDP (World Bank, 2022b).

Musukwa and Odhiambo (2020) explained that even though the impact of remittances on poverty is sensitive depending on the poverty proxy used in South Africa – for example, household consumption and mortality rate – remittances can significantly help to reduce poverty for South Africans.

South Africa is increasingly assisting foreign migrants in the country to return to their countries of origin. For example, in 2022, a joint effort by the Department of Home Affairs and UNHCR facilitated the voluntary repatriation of 49 of the more than 600 Congolese refugees who volunteered to return home (UNHCR, 2022; Mail & Guardian, 2022). With the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in 2019, some South Africans living abroad were very vocal about their desire to return home. According to the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (2020), the government has helped more than 3,000 South Africans to repatriate during the Covid-19 pandemic. During this time, the South African government played an essential role in assisting its nationals to come back home.

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

Key international organisations dealing with migration in South Africa are the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Labour Organization (ILO) and Doctors Without Borders (MSF). The IOM aims to improve the collection of data on migratory movements and internal displacements as well as to better manage situations at the borders, in the areas where the majority of the population lives, and where the presence of refugees and asylum seekers is more relevant.

The UNHCR plays a key role in the protection, education, and social assistance of refugees and asylum seekers, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and stateless persons. The UNHCR i) pursues international protection for asylum seekers and refugees to ensure that governments respect their obligations to protect refugees and people seeking asylum in South Africa, ii) chairs the Protection Working Group that is working with the South African Police Services to ensure timely intervention to prevent and respond to xenophobic attacks, and iii) advocates for conditions that are conducive to ensuring all refugees have access to seeking asylum. The UNHCR and its implementing partners run programmes that offer educational assistance to refugees and asylum seekers and grant social assistance to the most vulnerable refugees and asylum seekers through food vouchers, non‐food items, sanitary materials, social grants, and the like (UNHCR, 2015).

African Organisation of English-Speaking Supreme Audit Institutions. 2019. Auditor General Report: Performance Audit on Immigration Process for Illegal Immigrants at DFA – South Africa. Retrieved from: https://afrosai-e.org.za/2020/05/11/performance-audit-on-immigration-process-for-illegal-immigrants-at-dfa-south-africa/

Amit, R. & Kriger, N. 2014. Making migrants ‘il-legible’: The policies and practices of documentation in post-apartheid South Africa. Kronos, 40(1):269-290. Retrieved from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0259-01902014000100012

Atkinson, D. 2014. Rural-urban linkages: South Africa case study. Retrieved from: https://www.rimisp.org/wp-content/files_mf/1422297966R_ULinkages_SouthAfrica_countrycasestudy_Final_edited.pdf

Bello, O. & Olutola, A. 2022. Effective response to human trafficking in South Africa: Law as a toothless bulldog. Sage Open, 12(1). Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211069379

CIA World Factbook. 2022. South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/south-africa/

CIA World Factbook. 2023. South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/south-africa/

Crush, J. & McDonald, A. 2001. Evaluating South Africa immigration policy after apartheid. Indiana University Press. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4187430

Crush, J., Ramachandran, S. & Pendleton, W. 2013. Soft Targets: Xenophobia, Public Violence and Changing Attitudes to Migrants in South Africa After May 2008. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 64, Cape Town.

Democracy Development Program. 2022. Protecting the rights of migrant women entrepreneur in the informal economy. https://ddp.org.za/blog/2022/04/12/protecting-the-rights-of-migrant-women-entrepreneurs-in-the-informal-sector/

Department of Home Affairs. 2017. White Paper on international migration for South Africa. Retrieved from: http://www.dha.gov.za/WhitePaperonInternationalMigration-20170602.pdf

Department of Home Affairs. 2024. White Paper on citizenship, immigration and refugee protection: Towards a complete overhaul of the immigration system in South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202404/50530gon4745.pdf

Department of International Relations and Cooperation. 2020. Newsletter on the repatriation of South African citizens. Retrieved from: https://www.energy.gov.za/files/docs/Repatriation-newsletter-04052020.pdf

Floodlist. 2022. South Africa – 1 dead, 3 missing after floods in Gauteng. Retrieved from: https://floodlist.com/tag/south-africa

Gadisa, G., Sibanda, O., Vries, K. & Rono, C. 2020. Migration-related detention of children in Southern Africa: Developments in Angola, Malawi, and South Africa. Global Campus Human Rights Journal, 4(2):403-423. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.25330/935

German Network for Forced Migration Studies. 2020. Covid-19 and refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa. Retrieved from: https://fluchtforschung.net/covid-19-and-refugees-and-asylum-seekers-in-south-africa/

Ginsburg, C., Collinson, M.A., Gómez-Olivé, F.X., Gross, M., Harawa, S., Lurie, M.N. … White, M.J. 2021. Internal migration and health in South Africa: Determinants of healthcare utilisation in a young adult cohort. BMC Public Health, 21, 554. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10590-6

Independent Online (IOL). 2023. Flood wrap: Four confirmed dead, 70 homes destroyed, 151 left homeless in Durban following flash floods. Retrieved from: https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/kwazulu-natal/flood-wrap-four-confirmed-dead-70-homes-destroyed-151-left-homeless-in-durban-following-flash-floods-e4b25f81-2e25-453a-8434-763af70481b1

Institute for Security Studies (ISS). 2019. Women migrants: forgotten victims of South Africa’s xenophobia. Retrieved from: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/woman-migrants-forgotten-victims-of-south-africas-xenophobia

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2020. South Africa: Displacement associated with conflict and violence. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/figure-analysis-zaf.pdf

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2022. South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/south-africa

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2023. South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/south-africa

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). 2024. South Africa thunderstorms: LP, EC, MP, and FS 2024 – DREF operation MDRZA020. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/south-africa/south-africa-thunderstorms-lp-ec-mp-and-fs-2024-dref-operation-mdrza020

Mail & Guardian. 2022. Congolese living in South Africa voluntarily repatriated. Retrieved from: https://mg.co.za/news/2022-03-30-49-congolese-refugees-living-in-south-africa-voluntarily-repatriated/

Migration Data Portal. 2021. South Africa. Retrieved from: https://migrationdataportal.org/?t=2020&i=stock_abs_&cm49=710

Migration Data Portal. 2022. Migration Data in Southern African Development Community (SADC). Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/regional-data-overview/southern-africa

Migration Policy Institute. 2021. South Africa reckons with its status as a top immigration destination, apartheid history, and economic challenges. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/south-africa/south-africa-reckons-its-status-top-immigration-destination-apartheid-history

Musukwa, T. & Odhiambo, M. 2020. Remittance inflows and poverty dynamic in South Africa. Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2158244020983312

News24. 2023. More than 1000 Rawsonville residents displaced by floods. Retrieved from:https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/more-than-1-000-rawsonville-residents-displaced-by-floods-20230619

OECD/ILO. 2018. How immigrants contribute to South Africa’s economy. Paris, OECD Publishing. Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@migrant/documents/publication/wcms_635964.pdf

Peberdy S. 1997. Ignoring the history of undocumented migration is akin to ignoring those who have helped build South Africa. The Sunday Independent, 22 June. Retrieved from: www.queensu.ca/samp

Posel, D. 2006. Moving on: Patterns of labour migration in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dorrit-Posel/publication/286739729_Moving_on_Patterns_of_labour_migration_in_post-apartheid_South_Africa/links/6013dd1f92851c2d4dff5f0d/Moving-on-Patterns-of-labour-migration-in-post-apartheid-South-Africa.pdf

Reliefweb. 2022. South Africa: Floods and landslides. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/disaster/fl-2022-000201-zaf

Southern African Development Community (SADC). 2003. Charter of Fundamental Social Rights in SADC. Retrieved from: https://www.sadc.int/document/charter-fundamental-social-rights-sadc-2003

Statistics South Africa. 2011. Census 2011: Migration dynamics in South Africa. Pretoria. Retrieved from: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-01-79/Report-03-01-792011.pdf

Statistics South Africa. 2022. Equality in the job market still eludes women in SA. Retrieved from: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=16533

Statistics South Africa. 2023. Migration profile report for South Africa: A country profile 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/03-09-17/03-09-172023.pdf

Tevera, D. 2020. Imagining borders, borderlands, migration and integration in Africa: The search for connections and disjunctures. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-42890-7_2

The Guardian. 2022. ‘This is apartheid’: Cape Town slum residents condemn forced removals. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/nov/02/cape-town-slum-residents-condemn-forced-removals-apartheid

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2019. International migration stock 2019: South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2015. South Africa: Factsheet. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/operations/524d87689/south-africa-fact-sheet.html

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Homeward bound: Congolese refugees in South Africa opt to restart their lives in Kinshasa. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/afr/news/stories/2022/4/62603dee4/homeward-bound-congolese-refugees-in-south-africa-opt-to-restart-their.html

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023. South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/countries/south-africa#

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. UNICEF and The South African Red Cross partners to assist migrant children. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/press-releases/unicef-and-south-african-red-cross-partner-assist-migrant-children

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023. Technical brief one: Integrating child protection services. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/media/8306/file/ZAF-technical-brief-1-integrated-child-protection-services-2023.pdf

US Department of State. 2023. Trafficking in Person Report: South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/south-africa/

Van der Horst, S.T. 1971. Native labour in South Africa. London: Frank Cass & Co.

Voice of America (VOA). 2022. Malawi mandates quarantine for returnees from South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.voanews.com/a/covid-19-pandemic_malawi-mandates-quarantine-returnees-south-africa/6200409.html

Vosloo, C. 2020. Extreme apartheid: The South African system of migrant labour and its hostels. Retrieved from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1021-14972020000100001

Wentzel, M. & Tlabela, K. 2006. Historical background to South African migration. In Kok, P., Gelderblom, D., Oucho, J. & Van Zyl, J. (Eds), Migration in South Africa and Southern Africa: Dynamics and determinants. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

World Bank. 2022a. Personal remittances received (Current US$) – South Africa. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT?locations=ZA

World Bank. 2022b. Personal remittances received (% of GDP) – South Africa. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=ZA