Historical Background

Historical Background

Migration is not a new phenomenon in Somalia. However, the last 30 years have been characterised by the largest volume of migration in the country triggered by factors such as conflict, chronic insecurity, extreme poverty, famine, and the absence of an effective central government (UNHCR, 2023).

In the early 20th century, Somali seafarers who worked on colonial ships and students settled and formed communities in port cities in Western European countries such as the United Kingdom and Norway (IOM, 2017). The absence of an effective central government remains one of the key drivers of large-scale migration in Somalia. The country experienced its first military coup nine years after independence when the military junta under the command of General Mohammed Said Barre took over the country and established a democratic republic (Ibid). His government was challenged by the Somali National Movement in north-western Somalia, which turned into a clan-based civil war in 1991 and ended with the dissolution of the government (Ibid).

The ousting of the military junta created a power vacuum that the Transnational National Movement (TNG), which emerged from the war, could not sustain. This paved the way for the Islamic Court Union (ICU) (a coalition of Sharia courts and warlords) to take control of the southern parts of the country. The composition of the ICU includes Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs) like al-Shabaab which has gained much prominence in some parts of the country. Hence, the ICU sent fear waves to neighbouring countries like Ethiopia and Kenya which supported the Somalia military in conducting offensive military operations to weaken the NSAGs, as they pose a threat to regional security (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED), 2024). Continuous fighting in the country has collapsed the state and its institutions, making it one of the most fragile nations in the world and displacing more than 2 million Somalis, an estimated 18% of the population, to different parts of the world, predominantly in Africa (UNHCR, 2023).

Migration Policies

Migration Policies

At international level, Somalia forms part of several international migration protocols, including the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol and the OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa of 1969.

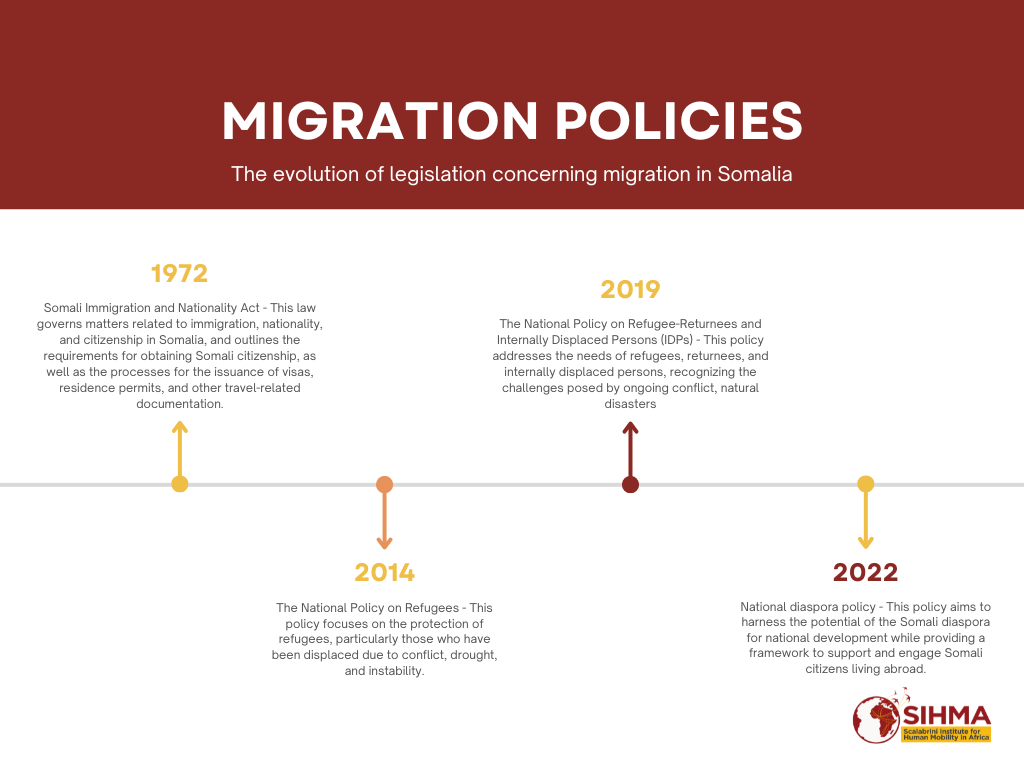

Timeline of Migration Policies in Somalia. Source: SIHMA

At national level, the government needs to face challenges such as political instability and recurrent attacks from Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs) in order to govern the country outside the capital Mogadishu. In addition, the government has not been able to develop a comprehensive migration policy framework. As a result, there are only a few laws or policies directly related to migration. These are presented in the table below:

|

Presidential Decree No. 25 of 2 June 1984 on the Determination of Refugee Status |

Defines the requirements for recognition of refugee status, the asylum procedure, and the admission of asylum seekers |

|

Pre-1991 Penal Code |

Prohibits human trafficking, slavery, and forced labour |

|

Somalia Immigration Law (Law No. 72/1995) |

Defines powers and duties of immigration officers, conditions for entry, stay, and work in the territory of Somaliland |

|

Republic of Somaliland Citizenship Law (Law No. 22/2002) |

Provides for matters related to citizenship |

|

Refugees and Asylum Seekers (Law No. 103/2023) |

Seeks to provide protection to refugees and asylum seekers and requires the state to continue to recognise refugee status accorded by UNHCR |

|

National Action Plan 111 |

Seeks to eradicate statelessness |

Source: MGSOG, 2017 & UNHCR, 2024

Although the Somali government has improved its Border Management System to streamline the processing of migrants entering the country, the government does not have adequate resources and manpower to enforce the limited policies to ensure the protection of migrants and other vulnerable groupings within its border. The fragility of the state makes it even more challenging to adhere to migrant policies.

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

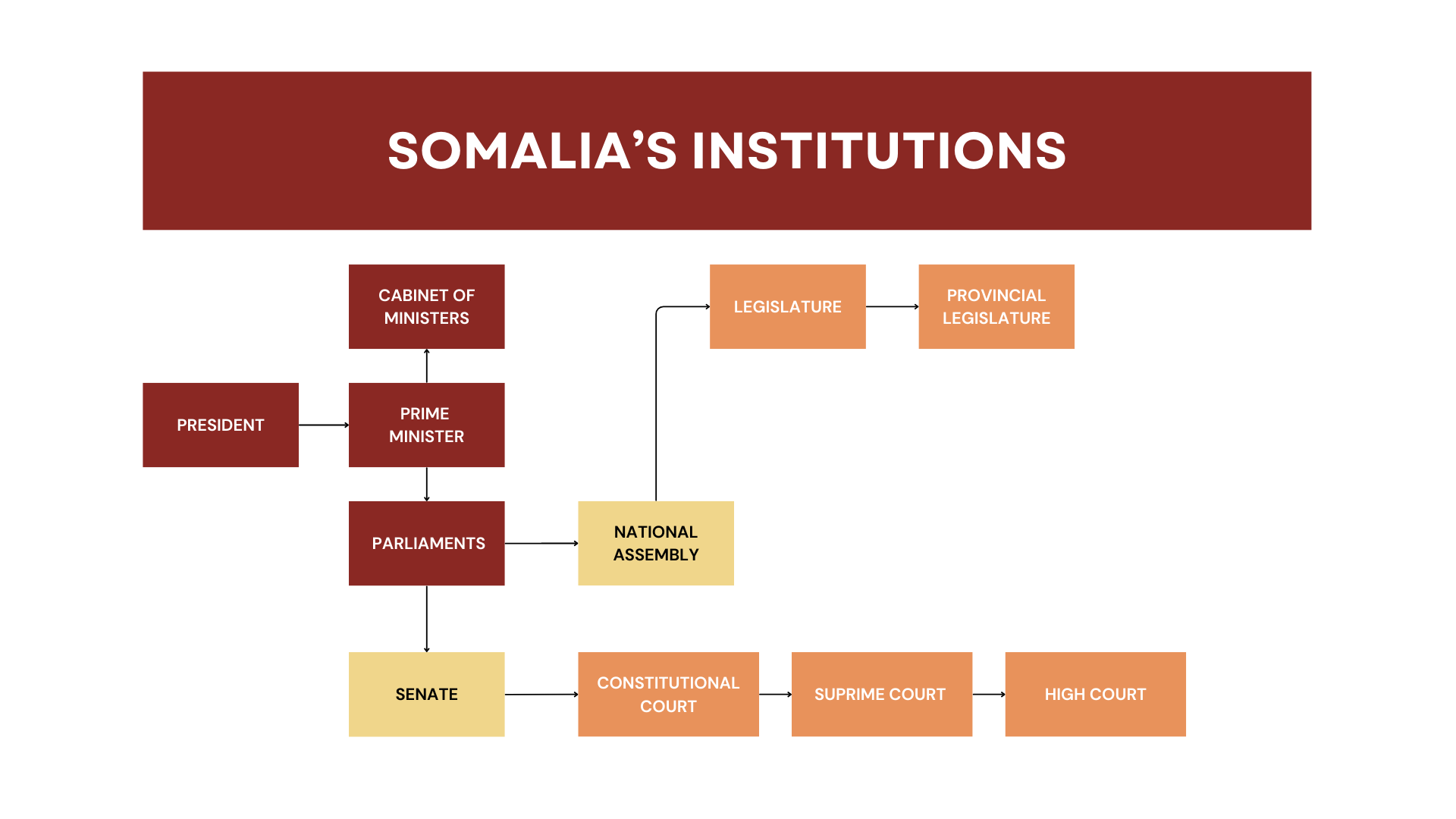

The Federal Government of Somalia supports people on the move through various ministries. The Ministry of Interior, Federal Affairs and Reconciliation, acting through the National Commission for Refugees and IDPs (NCRI), is the lead ministry handling migrant affairs, implementing the National Policy on Refugee-Returnees and Internally Displaced Persons, and overseeing all activities supporting durable solutions for refugee-returnees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) (National Legislative Bodies/National Authorities, 2019).

Somalia's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

Other state actors involved in migrant affairs include the Ministry of Planning, Investment and Economic Development, the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, the Ministry of Public Works, Reconstruction and Housing, the Ministry of National Security, the Ministry of Women and Human Rights Development, and the Ministry of Youth and Sports (Ibid).

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

There are no recent statistics on internal migration in Somalia as mobility within the country is generally characterised by forced displacement. However, because of the insecurity associated with rural areas, there is a high concentration of people in urban areas.

According to Knoema (2024), over the past 50 years, Somalia has experienced substantial urban population growth from 25% to 47.9% in 2023.

Internally Displaced Persons (conflict/violence and disaster)

Internally Displaced Persons (conflict/violence and disaster)

In Somalia, the population is highly vulnerable to climatic and man-made shocks caused by weak governance, conflict, socio-economic underdevelopment, and social insecurity. The complexity and protraction of the Somali humanitarian crisis is the result of decades of inter-clan and armed conflicts, and recurring climatic shocks, leading to the internal displacement of an estimated 5.9 million Somalis by the end of 2023 (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), 2024).

Over the past three decades, fighting between the state military and NSAGs, particularly al-Shabaab, has been one of the main sources of conflict and violence-related internal displacement in Somalia. According to the IDMC (2024), between 2020 and 2023, the country recorded 293,000 to 673,000 internal displacements, resulting in 3 million to 3.9 million internally displaced people within the same time frame. For example, in February and March of 2023, clashes between the Somaliland National Army and the SCC-Khahumo forces of the Dhulbahante clan triggered the displacement of an estimated 157,000 people in Laas Aanood, the capital of the northern Sool region (Ibid).

Disaster-related displacement in Somalia is mostly associated with floods and droughts. According to the IDMC (2024), from 2021 to 2023, an estimated 271,000 to more than 2 million people were internally displaced in the country. For example, in the southern regions of Bay, Gedo, and Lower Shabelle, drought displaced an estimated 331,000 people while floods displaced an estimated 1.7 million people across the country (Ibid). Most parts of Somalia are burdened by the conflict and violence caused by NSAGs. The precarious living conditions of people are exacerbated by hazardous climatic conditions, resulting in food scarcity and food insecurity.

Immigration

Immigration

As a country plagued with conflict, violent extremism, and poor climatic conditions, its ability to attract large volumes of immigrants is compromised. Also, there are no reliable statistics on immigrants in Somalia. The only available information pertains to international migration stock in the country as provided by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA).

According to UN DESA, as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), in 2010, there were 48,100 international migrants in Somalia, with the figure dropping to 41,000 in 2015 and growing to 58,600 in 2020. Most of the immigrant population in Somalia are transit migrants from the Horn of Africa, mostly from Ethiopia, who use irregular migration channels to go to other countries, for example, Western Asia (Yemen) (Expertise France, 2017).

Female Migration

Female Migration

Due to the ongoing political instability in Somalia, very limited research has been conducted on aspects of migration such as female migration in the country. According to the World Bank (2024), female migrants constituted 47.9% of Somalia's international migration stock in 2019.

Most female migrants in Somalia are from the Horn of Africa and they are mostly transit migrants (see section on immigration).

Children

Children

As one of the poorest countries in the world that experiences recurrent levels of conflict, violence, and disaster, many children under the age of 18 years are bound to be on the move in search of safety and better opportunities.

According to an article published by the European Union (2021), each year approximately 450,000 children are on the move in Somalia. Movement in an environment characterised by insecurity exposes children to the risk of rape, sex trafficking, crime, and mental health challenges. To help counter risky migration, UNICEF works in partnership with the government, universities, and civil society to support and protect child migrants – for example, through the provision of vocational training, scholarships, and access to legal services (UNICEF, 2024). However, despite UNICEF’s efforts and the risks associated with migration, the political instability and economic vulnerability of the country make child migration a survival mechanism.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Because of the political instability, hazardous climatic conditions, and recurrent terrorist attacks, Somalia is well known globally as a refugee-origin country and not a country that receives refugees. According to UNHCR (2024), there are an estimated 761,221 Somalia refugees from 114,788 households, mostly located in Ethiopia (358,768), Kenya (301,357), Uganda (48,756), Yemen (38,878), and Djibouti (13,462). However, because of the political instability in Yemen and parts of Ethiopia (Tigray region) (neighbouring countries to Somalia), the country has become a beacon of hope to those fleeing persecution from these countries.

In May 2024, there were an estimated 18,699 refugees and 20,776 asylum seekers in Somalia, mostly from Ethiopia (66%), Yemen (29%), Syria (4%), and other countries (1%) (UNHCR, 2024b; 2024c). Because of growing insecurity concerns in the hinterlands, the majority (74%) of the refugees and asylum seekers in the country are located in urban and peri-urban areas, across the Wogooyi, Galbeed, and Bari regions in the northern part of Somalia (UNHCR, 2024c). The presence of refugees and asylum seekers in Somalia, a country in which many are fleeing to seek refuge elsewhere, is an indication of the dire situation in which these vulnerable people find themselves as they now need to choose between two evils, with Somalia being the lesser evil.

Emigration

Emigration

Movement from Somalia is generally informed by forced displacement. The majority of Somalis living outside the country are either refugees or asylum seekers.

Labour Migration

Labour Migration

Statistics on the flow of labour migrants in Somalia are not available. As of June 2024, as reported by the International Labour Organization (ILO) (2024), Somalia had no dedicated labour migration policy.

Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking

Weak governance, political instability, violent extremism, and transnational organised crime have made Somalia a fertile ground for diverse transnational criminal markets including human trafficking. For the past 22 years, Somalia has been a source and transit country for human trafficking (US Department of State, 2024). Despite stringent penalties for human trafficking – ranging from five to 20 years imprisonment – the scourge of human trafficking remains a major concern in Somaliland as endemic poverty continues to make the population vulnerable to human trafficking. The victims of human trafficking include children in forced labour in agriculture, domestic work, herding, selling, crushing stones, fishing, and sex labour in Somaliland (Ibid). Some victims are exploited into sex trafficking abroad in Europe and North America, especially children and women, through false promises of lucrative jobs (Ibid). Traffickers also exploit Somali children into street begging in Djibouti, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

The identified human trafficking routes in Somaliland include a northern route to Europe via Libya; an eastern route to Europe via Turkey; a southern route to Kenya, Tanzania, or South Africa; and a route from South-central Somalia through Puntland onward to Yemen via the Bab al-Mandeb Strait (Ibid). The office of the Attorney General reported 57 ongoing trafficking investigations (24 labour trafficking cases, 27 sex trafficking cases, and 6 unspecified trafficking cases), prosecuting 77 alleged traffickers, and convicted 67 traffickers (Ibid). Although the US Department of State (2024) indicated that government officials are complicit in acts of human trafficking, Somalia did not report any ongoing investigations, prosecutions, or convictions, despite reports from NGOs assisting vulnerable migrants indicating that these NGOs have supported 6,612 migrants during the previous reporting year and 2,272 migrants in this reporting year, which in the mix are potential cases of human trafficking aided by government officials (Ibid). The inability of the state to adequately identify victims, prosecute alleged perpetrators, and convict traffickers only makes the illegal venture of human trafficking a lucrative source of income for traffickers.

Remittances

Remittances

As a country prone to recurrent military attacks and volatile to hazardous climatic conditions, remittance flow constitutes an important source of income. Every year, the Somali diaspora sends approximately $1.3 billion back home to family and friends (Oxfam, 2024). This amount does not take into account the remittances that flow through the irregular channels. The relevance of remittance flow cannot be underestimated as it exceeds all development and humanitarian assistance, accounting for between 20% and 40% of the economy (Ibid).

Remittance flow contributes enormously to reducing household poverty in Somalia. For example, the average household income of remittance-receiving households in 2017 stood at $743, surpassing the average per capita income of $535 (World Bank, 2019). Therefore, households that receive remittance flow are more likely to be less poor, consume more, have higher child school enrolment rates, and rely less on agricultural livelihoods adversely affected by hazardous weather conditions (Ibid). In addition to immediate consumption, remittances can be used as leverage to access the capital market, contribute to international reserves, help finance imports, and improve the country’s current account position (Ibid). Remittance is therefore a lifeline to the country’s economy. Despite its relevance to households as well as the economy, the flow of remittances is subject to challenges such as the high cost of remitting and inadequate remitting channels.

Returns and Returnees

Returns and Returnees

Although the political and economic situation in Somalia is unstable, Somalis living abroad continuously find ways to return home both voluntarily and with the support of UNHCR. Since December 2014, UNHCR has supported the return of 93,721 Somali refugees (UNHCR, 2024a). Also, since 2015, an estimated 42,984 Somalis spontaneously returned from Yemen (Ibid). In an attempt to process and provide safe arrival to returnees, UNHCR provides support to the four waystations (Mogadishu, Baidoa, Kismayo, Dhobley) and two reception centres (Berbera, Bossaso) (UNHCR, 2024b).

To ensure long-term sustainable reintegration, UNHCR supports returnees through cash assistance and livelihood programmes (Ibid). Despite the assistance provided by UNHCR, returnees are displaced in camps where they are confronted with challenges such as finding employment, decent housing, a secure living environment, and educational opportunities for their children (Owigo, 2022).

International Organisations

International Organisations

Key international organisations dealing with migration-related issues in Somalia include the UN, UNHCR, and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which seek to identify migrant routes, monitor outflows and inflows through the major points of transit, and promote international agreements for the protection and facilitation of returnees. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) intervenes to develop resilience to environmental phenomena and agricultural realities while monitoring the cyclical movements of nomadic herders, together with the impact of their movements on the exacerbation of local tensions. The work of NGOs and international agencies is majorly supported by local civil society groups and by the diaspora’s efforts for infrastructural development. The former is crucial for the development of targeted interventions because civil society can facilitate access to marginalised groups, identify issues, and foster productive dialogue. Although civil society is subjected to challenges such as lack of unity, internal governance challenges, and sustainability issues, civil society organisations remain a reliable vehicle through which government and international organisations can implement initiatives due to these organisations’ credible representation of community voices and their informative capacity (Osman, 2018). Indeed, civil society organisations play a vital role in Somalia’s development through policy influence, skills transfer, and investment (IOM, 2021). The Somali diaspora supports local institutions providing services and emergency relief to various households during crises (Ibid). International organisations in partnership with civil society remain an important partner in providing relief and searching for lasting solutions to the crises plaguing the country.

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED). 2024. What’s next for the fight against al-Shabaab? Retrieved from: https://acleddata.com/2024/09/04/whats-next-for-the-fight-against-al-shabaab-in-kenya-and-somalia-august-2024/#

CIA World Factbook. 2024. Somalia. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/somalia/

European Union (EU). 2021. Somalia: Protecting children on the move. Retrieved from: https://trust-fund-for-africa.europa.eu/news/somalia-protecting-children-move-2021-09-20_en

Expertise France. 2017. Somalia country statement: Addressing migrant smuggling and human trafficking in East Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.expertisefrance.fr/documents/20182/234347/AMMi+-+Country+Report+-+Somalia.pdf

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2024. Country profile: Somalia. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/somalia/

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2024. Somalia advances towards safe migration with successful national consultation workshop and TWA meeting. Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/somalia-advances-towards-safe-migration-successful-national-consultation

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Enabling a better understanding of migration flows (and its root-causes) from Somalia towards Europe. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/dtm/somalia_dtm_201704.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2021. IOM welcomes Somalia’s development of its national diaspora policy. Retrieved from:

Knoema. 2024. Somalia: Urban population as a share of total population. Retrieved from: https://knoema.com/atlas/Somalia/Urban-population

Maastricht Graduate School of Governance (MGSoG). 2017. Somalia migration profile: Study on migration routes in the East and Horn of Africa. Retrieved from: https://i.unu.edu/media/migration.unu.edu/publication/4717/Migration-Routes-East-and-Horn-of-Africa.pdf

National Legislative Bodies/National Authorities. 2019. Somalia: National policy on refugee-returnees and internally displaced persons. Retrieved from: https://www.refworld.org/policy/strategy/natlegbod/2019/en/122553

Osman, F. 2018. The role of civil society in Somalia’s reconstruction: achievements, challenges and opportunities. Retrieved from: https://www.saferworld-global.org/resources/news-and-analysis/post/775-the-role-of-civil-society-in-somaliaas-reconstruction-achievements-challenges-and-opportunities

Owigo, J. 2022. Returnees and dilemmas of (un)sustainable return and reintegration in Somalia. Retrieved from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ahmr/article/view/259847/245334

Oxfam. 2024. Remittances to Somalia. Retrieved from: https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/issues/economic-well-being/remittances-to-somalia/

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Annual results report: Somalia. Retrieved from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/EHGL%20-%20Somalia%20ARR%202023_0.pdf

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024a. Refugees in Somalia. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/horn

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024a. Somalia: Refugee returnees. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/somalia/somalia-refugee-returnees-january-2024#

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023. Somalia refugee crisis explained. Retrieved from: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/somalia-refugee-crisis-explained/

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024b. Somalia. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/som

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024b. Voluntary return and reintegration. https://help.unhcr.org/somalia/en/voluntary-return/

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024c. UNHCR Somalia: Refugees and asylum seekers (31 March 2024). Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/somalia/unhcr-somalia-refugees-and-asylum-seekers-31-march-2024

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Child protection: Protection for every child, regardless of nationality or immigration status. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/somalia/child-protection/child-migration

US Department of State. 2024. Trafficking in person report: Somalia. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/somalia/

World Bank. 2019. Somali poverty and vulnerability assessment: Findings from wave 2 of the Somali high-frequency survey. Retrieved from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/929151578943308865/pdf/Somali-Poverty-and-Vulnerability-Assessment-Executive-Summary.pdf

World Bank. 2024. Migrants, female (% of internal migrant stock). Retrieved from: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/indicator/sg-pop-migr-fe-zs