HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Niger is positioned at the crossroads of the migratory routes in West and Central Africa (IOM, 2016). Hence, Niger has become one of the main transit countries for migrants originating from West and Central Africa, moving to North Africa, and migrating irregularly across the Mediterranean (ibid). Despite residing in a region of political instability and violent extremism, Niger demonstrated some relative political and social stability for 13 years, starting in 2010, until it was subjected to its sixth military coup in 2023.

Owing to the closure of the border between Chad and Libya and the growing dangers on the route through Mali to Algeria, the migration route through Niger has increased in relevance (IOM, 2016). Traditionally, Nigeriens have migrated in an attempt to cope with the dire economic circumstances in the country (IRI, 2020). Migration has generally been seasonal. Circular migration has also been common in the region, with Nigeriens migrating to Libya and Algeria and returning home after several years (IOM, 2016). Recently, however, migration has become more frequent and irregular, characterised by increasing danger and uncertainty (IRI, 2020). This spike in irregular and unconventional migration has been influenced by two key developments – the fall of the Gaddafi regime and the passing of the Anti-Smuggling Law by the Nigerien government in 2015 (ibid).

Niger has, for decades, experienced regular patterns of migration. The steady flow of migrants from West and Central Africa accelerated quite rapidly after the fall of the Gaddafi regime in Libya in 2011. From 2015 to 2016, migration reached its peak – an estimated 330,000 migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers travelled through Niger, with 170,000 moving through the town of Agadez (ibid). The town of Agadez and other communities along the main migratory routes benefitted significantly from this boom in migration. Local economies began to flourish (the establishment of stalls that sell food, water and batteries to migrants), and migration became a primary source of income for many of these communities (ibid).

Concerned about the growing numbers of African migrants heading to Europe, the European Union attempted to incentivise Niger with aid and assistance in return for curbing irregular migration through an agreement between the European Union and Niger (ibid). In 2015, this led to the implementation of anti-smuggling laws (Law 2015-36) that criminalised migrant transportation from Agadez to Libya, causing migration flows to drop from 333,891 in 2016 to 43,380 in 2018 (ibid). However, the military Junta that took over power in 2023 abrogated the law in November of the same year.

Migration in Niger, as across West and Central Africa, is driven by negative factors such as economic circumstances, dire environmental realities, violence, and persecution. Emigration in Niger plays a key role in sustaining the livelihoods of rural communities and often takes the form of seasonal labour migration toward neighbouring countries. Before 2023, Nigeriens typically migrated internally or to nearby countries in the region, such as Nigeria, Libya, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Algeria. However, after the military coup in Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali, ECOWAS slammed all three countries with sanctions that restricted movement from the three sanctioned countries to other member-state countries. In retaliation, the three countries indicated their intention to withdraw from the regional organisation.

Matters of migration in Niger are largely managed with a laissez-faire approach – migration is not considered a key issue for the country (Jegen, 2020). On a national level, a clear policy on migration is yet to be adopted. In 2007, the state established a special inter-ministerial committee on migration policy development which has since created the first draft of a policy document (ICMPD, 2015). The instability in the region, growing danger, and irregular migration now call for a holistic response to migration management from the government in order to ensure Niger’s stability.

MIGRATION POLICIES

MIGRATION POLICIES

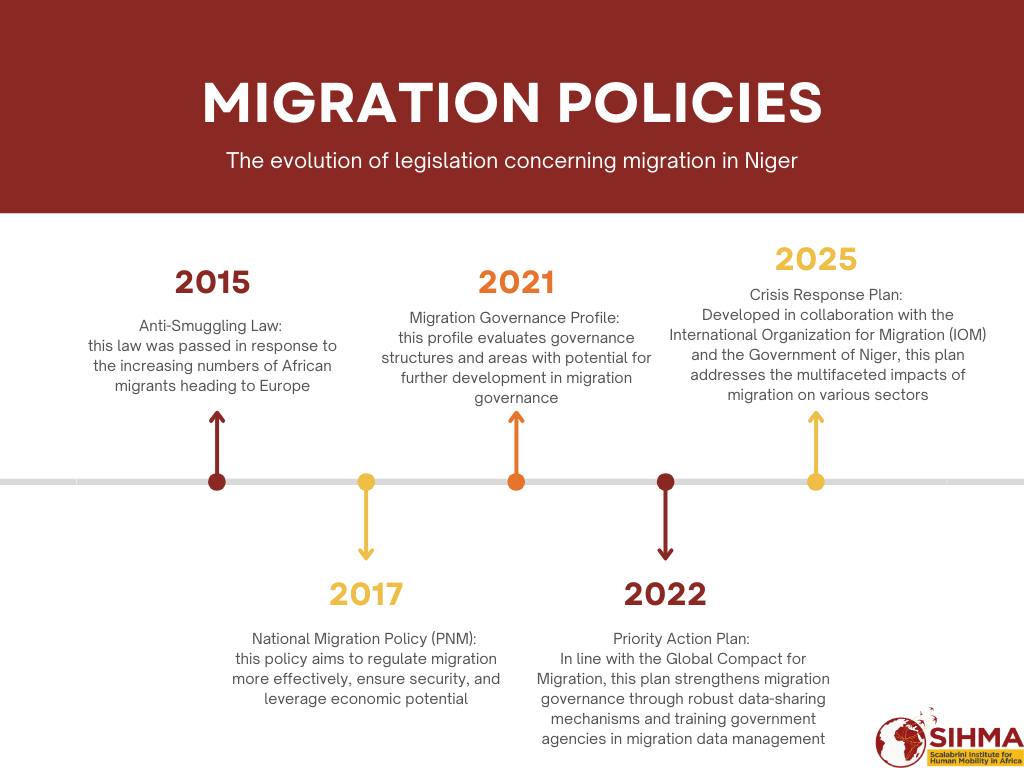

Several migration-related legal frameworks govern migration in Niger. Niger is a party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol and to the OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa of 1969. Despite the establishment of an inter-ministerial committee on migration policy development in 2007 and the creation of a first policy draft document in 2014, Niger has yet to adopt a national migration policy (IRI, 2020). The Inter-Ministerial Committee in charge of the Elaboration of a National Migration Policy is placed under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior and is composed of officials from the main ministries involved in the management of migration (ICMPD, 2015; IOM, 2015).

Timeline of Migration Policies in Niger. Source: SIHMA

Historically, migration within the Nigerien context has not been seen as a high priority for the government. This can be ascribed to the small percentage of the population involved in or affected by migration and to the urgency of issues such as security, regional political instability, and climate change (Jegen, 2020). Governance issues such as low state capacity, economic inequality, and corruption have resulted in the state falling short on the provision of basic services and migration management (IRI, 2020). Policies and programmes have failed to address the root causes of migration while simultaneously inflaming the causes. The governance barriers to effective migration control that Niger needs to overcome include lack of resources, factionalism in government, impunity, and low state capacity (ibid). Many Nigeriens who emigrate believe that the government can prevent irregular migration and skilled emigration by creating alternative solutions for the vast majority of the population who are unable to find jobs (ibid). Gaps in governance affect people’s likelihood to migrate – weak and incapable governance produces migration as a response. To engage with and address migration effectively, the Nigerien state needs to expand existing governance frameworks to manage new forms of human mobility and enhance the resilience of Nigerien migrants (ibid). However, despite migration mismanagement, Niger’s relative stability since 2010 and location have contributed to it becoming a strategic ally of the United States in terms of counterterrorism and stability and the management of migration in the region (ibid). However, after the military coup of July 2023, the relationship turned sour as the military Junta in power revoked the military cooperation deal with the US.

GOVERNMENTAL INSTITUTIONS

GOVERNMENTAL INSTITUTIONS

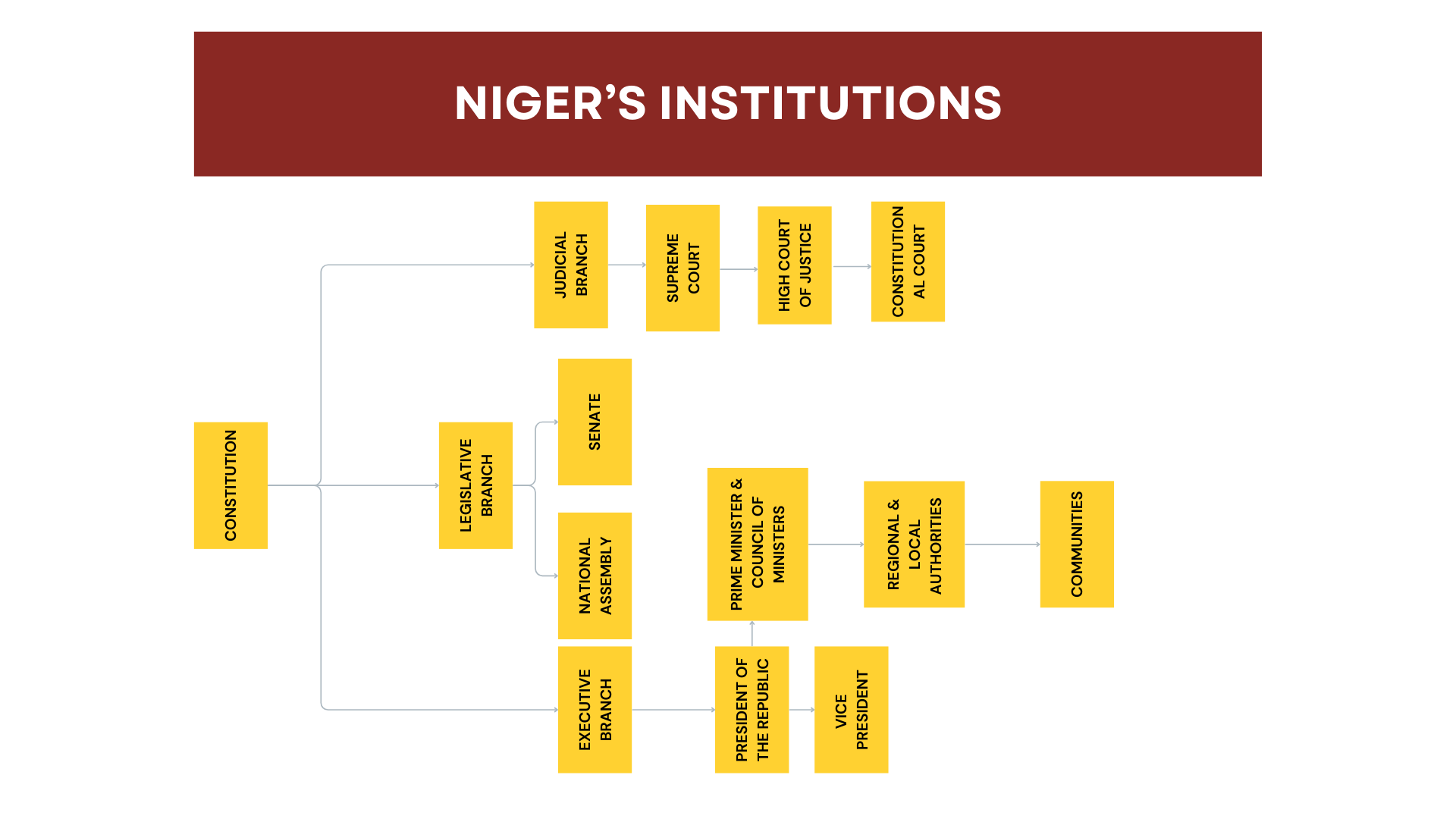

The cabinet of the Prime Minister is in charge of the political response to migration and cooperates closely with the Ministry of the Interior (Jegen, 2020). The three ministries that mainly deal with migration issues are the Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Justice (ibid). The Ministry of Justice hosts the National Commission and the National Agency for the Fight against Trafficking in Persons (ibid). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs hosts the Directorate General of Legal and Consular Affairs, which is responsible for travel documentation, while the Directorate for Nigeriens Living Abroad and the High Council for Nigeriens Abroad are responsible for policies and programmes pertaining to diaspora relations (ibid).

Niger's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

National authorities appear to be rather flexible in their approach to dealing with irregular migration since it is not considered a major threat to Niger, and the removal of foreigners is very rare as a result of their irregular migration status (ICMPD, 2015). Irregular migrants are generally only removed if they commit a criminal offence in the country. However, as a result of the political instability and terrorist threats in the region, national authorities have begun removing foreigners more frequently (ibid).

INTERNAL MIGRATION

INTERNAL MIGRATION

Internal migration in Niger is strongly driven by the search for work and seasonal changes. Between 2016 and 2019, Niger registered 1,055,214 migrants – 16% of whom travelled within the country (IOM, 2020). A significant decline in migration flows was witnessed after the government of Niger implemented Law 2015-36 in 2015, criminalising irregular migration (IOM, 2020a). Internal migration within Niger takes on many different forms. Historically, pastoralists have moved over hundreds of kilometres with their livestock during the dry and rainy seasons; merchants move from market to market in local and regional areas on a seasonal basis; Koranic students often move to work or study with a particular marabout (spiritual healer); and labour migrants move across the country or to other countries in the region for work opportunities provided by gold mines, oil-drilling sites, and crop-raising areas (Turner & Teague, 2019). Migration profiles across Niger differ from region to region. During higher rainfall periods, movements occur to the north. Long-distance seasonal movements are very costly and are more likely to only be considered by families with easy access to cash (ibid). In general, seasonal migrants will try to resettle in urban centres such as Niamey before deciding to migrate to more distant destinations within Niger or Nigeria (ibid).

Migration in Niger seldom involves entire families. Traditionally, only certain members of the family migrate, leaving the remainder of the family at a home base (ibid). Since migrants often only earn a subsistence wage, one of the financial benefits of the labour migration process is having one less person at home to feed (ibid). In addition to being a source of livelihood, internal migration in Niger also contributes to the personal spiritual growth of young migrants.

INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS, CONFLICT AND DISASTERS

INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS, CONFLICT AND DISASTERS

Over the past few years, forced migration and internal displacement started to play a key role in Niger’s migration profile. It has gained increased relevance due to the deteriorating political situation in neighbouring countries (Jegen, 2020). Both conflict-related and disaster-related displacement characterise communities in Niger. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC, 2024), flooding caused by changing weather patterns, especially during the rainy season from July to November, is a main driver of disaster-related displacement in Niger while intercommunal violence orchestrated by non-state armed groups (NSAGs) predominantly between pastoralists and farmers is the main driver of conflict-related displacement.

The IDMC (2024) mentioned that, by the end of 2023, there were an estimated 347,000 people in displacements associated with conflict and violence. In 2023, conflict and violence also displaced an estimated 181,000 people (the highest figure recorded since 2015) in the regions of Diffa and Tillabéri. In the Diffa region that borders Nigeria and Chad, NSAGs displaced an estimated 44,000 people while in the Tillabéri region that borders Mali and Burkina Faso NSAGs displaced an estimated 104,000 after the military took over power. In terms of disaster-related displacement, in 2023, floods displaced an estimated 95,000 people in Niger, mostly from the Maradi region.

In Niger where agriculture constitutes a major source of livelihood, disaster-related displacement as a result of crop destruction or conflict-related displacement that forces people to move from their communities contribute to food insecurity and misery to the displaced population and the entire country.

IMMIGRATION

IMMIGRATION

Owing to its geographical position, Niger has become a major hub for movements toward Libya, Algeria, and the Mediterranean (UNHCR, 2021). Between 2016 and 2019, Niger registered 1,055,214 migrants with 55% travelling from Niger (IOM, 2020a). Following the political crises in Mali and Libya in 2011, Niger became a popular transit destination (ibid). Migration flows in West Africa have traditionally been intra-regional. Before the July 2023 military coup, the adoption of the Free Movement Protocol between the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) intensified migration across the region. Several key events have affected migration routes and flow in Niger between 2010 and 2019: The instability in Libya has led to fewer border controls and migrants being able to cross into Niger more easily; the adoption of the now abrogated 2015 Law criminalising irregular migration in Niger has led to an increase in the number of checks by law enforcement actors along migration routes, further leading to many migrants finding themselves stuck in transit towns; and the discovery of gold in Djado, north-eastern Niger, led to a rush of migration of prospective gold miners in 2014 (ibid).

While Niger cannot be considered a significant destination for international migrants, it was a very important country of transit for sub-Saharan African migrants, mainly from ECOWAS states when Niger was still an ECOWAS member. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA, 2021), there were 348,000 international migrants in Niger as of 2020. International migrants constitute 1.3% of the total population in Niger (ibid). Most of the international migrants in Niger come from West and Central Africa. According to IOM data, almost half of the registered migrants come from just two countries – Guinea (24%) and Senegal (21%) (IOM, 2016). Other top nationalities of migrants include Cameroon (9%), Côte d’Ivoire (8%), Guinea-Bissau and Gambia (7%), and Mali (6%) (ibid). The majority of the international migrants in Niger are male (64%) and between the ages of 18 and 29 (72%) (UN DESA, 2019). Only 5% of the total are minors (younger than 18 years old) and only 4% are aged 40 or older (ibid). The majority of the international migrant stock is single (58.5%), with only about a third declaring they were married (ibid).

Niger is a destination country for people from the region looking for economic opportunities. Work in areas such as the gold and uranium mines attracts migrants from other West and Central African countries (IOM, 2020a). In 2019, the IOM reported that 131,892 migrants stated Niger as their final destination (ibid). Nationals from ECOWAS member states tend to migrate and settle in Niamey (35.5% of international migrants), Tillabéri (18%), and Niasso (13%) while migrants from other African countries tend to migrate and settle in Diffa (34%), Niamey (29%) and Tahoua (15%) (ICMPD, 2015). High-skilled international migrants tend to be employed in the energy sector while low-skilled members tend to be employed in the construction sector (ibid).

In Niger, transiting across the country can be extremely timely and expensive – think of the financial cost of travelling through the Sahara Desert (ibid). Thus, it is common for migrants to pause their trip to Europe in Niger in order to earn more money for the whole journey. Cities in Niger such as Agadez, Arlit, and Dirkou have become popular stopover zones for migrants who want to prepare for the remainder of their trip, and as an initial place of return for expelled or stranded migrants (ibid).

FEMALE MIGRATION

FEMALE MIGRATION

In 2020, an estimated 54% of the approximately 350,000 migrants in Niger were women and girls, with a cross-section of them being Nigerian female migrants in transit – mostly to Algeria and Libya (UN Women Niger, 2021). These female migrants in transit are four times more at risk than men for sexual violence and 1.5 times for physical violence – with 51% committed by security forces and police and 10% by immigration officials (ibid).

Female international migrants tend to occupy jobs in sectors where Nigerian women are not employed, owing to cultural traditions and restrictions (ICMPD, 2015). In 2020, only 21 women migrant workers, mainly from Turkey and France, were granted work permits in Niger – with most of them working in the informal sector in small shops or restaurants, as sex workers (mostly in urban areas), and as domestic workers (UN Women Niger, 2021). The informal economy therefore plays an important role as a source of livelihood for most migrant women in Niger.

MINORS

MINORS

As a transit country to Europe and parts of Africa, Niger is a host to a significant number of migrant children. According to UN DESA (2020), as cited in the Migration Data Portal (2021), 32.9% of the total number of international migrants (114,525) were migrants 19 years of age and younger. Some of these child migrants get into the country unaccompanied. For example, in 2018, the IOM in its six transit centres assisted 1,473 accompanied migrant children and 346 unaccompanied migrant children.

The attempt by some European and North African countries to curtail irregular migration resulted in the expulsion of 200 children of different nationalities from Algeria to Niger (UNICEF, 2018). Some of these children are returned to impoverished communities where basic services like education and health care are inadequate or non-existent, reducing their options for a better life in the future.

REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

Because of the complex humanitarian and security crises in Libya, Niger has become an alternative space for protection. This includes the large numbers of asylum seekers and refugees unable to reach Europe and those deported from Algeria onto Nigerien territory (UNHCR, 2020). In 2019, Niger saw an increase of 14% of people of concern seeking refuge in the country (from 386,978 to 441,899 in 2019) (ibid). The number of those seeking refuge in the country almost doubled in 2022, as it stood at 711,642 (UNHCR, 2022). Of this total figure, refugees and asylum seekers totalled 295,877, representing 42% of the total number of persons of concern in Niger (ibid).

After the military coup of July 2023, the number of people of concern in the country as of July 2024 increased to 967,585, and refugees and asylum seekers totalled 413,906 (UNHCR, 2024a).The refugees and asylum seekers in Niger come from Nigeria (237,716), Mali (124,877), and various other countries (51,314) (ibid). Refugees and locals in Niger live side by side within the communities. In addition to living in the urban areas of Agadez and Niamey, Malian and Burkinabe refugees are predominantly located in the Tillabéri and North Tahoua regions while those from Nigeria are mostly in the South Tahoua and Maradi regions and those from the Lake Chad Basin are mainly located in the Diffa region (UNHCR, 2024b).

Although Niger continues to receive refugees from other parts of the continent, the financial sanctions imposed on the country by ECOWAS, the European Union, and Western donors because of the July 2023 coup adversely affect the country’s ability to support these vulnerable refugees and asylum seekers.

EMIGRATION

EMIGRATION

Historically, emigration flows from Niger were predominantly those of low-skilled workers towards coastal countries in West Africa, such as Côte d’Ivoire. Since the end of the 1990s, labour emigration has largely been driven by three main factors: population-driven land scarcity, poverty, and climate change (Turner & Teague, 2019). With a population growth rate of 3.66 (Index Mundi, 2020), Niger has one of the highest population growth rates in the world with a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.400, which positions it at 189 out of 191 countries (UNDP, 2023). Also, it is the least resource-endowed country in the Sahel region (Turner & Teague, 2019). Poverty and resource scarcity play a major role in the decision to emigrate as the bulk of the country’s economy is dependent on rain-fed agriculture.

Labour emigration is more than just an economic activity – emigrating is also an act of independence and individualisation from the head of the household (ibid). According to the International Centre for Migration Policy Development, there were an estimated 402,000 Nigerien emigrants in 2020 (ICMPD, 2022). The majority of emigrants from Niger find themselves in Nigeria (37.8%), Libya (12.6%), Côte d’Ivoire (12.4%), Benin (8.3%), Ghana (7.7%), Togo (5.2%) and Cameroon (3.5%) (ibid). Nigerien migration towards Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member states is limited, with an estimated 3% of migrants from Niger residing in European countries (ICMPD, 2015). Countries in Europe where migrants from Niger have been registered include France, Belgium, Italy, and Germany (ibid).

Nigerien emigration has traditionally been a male phenomenon, owing to traditional cultural values that limit the possibilities for women to migrate on their own (ibid). In the western Nigerien region, young men make up the vast majority of labour emigrants, but in the Hausa-dominated areas in central Niger, there is greater involvement of women in emigration (ibid). Nigerien migrants tend to be low-skilled (mirroring the level of education across the country) and generally occupy jobs in the agricultural sector. Larger households tend to have more migrants, whereas smaller households tend to be poorer and rely on all members of their family as they have a limited ability to hire labour (ibid). Emigration from Niger is generally temporary and seasonal, corresponding with seasonal agricultural activities (ibid). In ECOWAS member states, Nigerien migrants usually stay in the country for six to seven months, while in countries outside of the region, the stay often lasts for periods of one to two years (ibid). Although migration is shaped and partly influenced by culture in Niger, emigration for the most part is seen as a mechanism to escape poverty.

LABOUR MIGRATION

LABOUR MIGRATION

Due to the high levels of unemployment in Niger, the country is not an attractive destination for labour migrants. However, it remains a very strategic transit migration route for labour migrants who are attempting to reach Europe or the Maghreb region (ILO, 2023). The policy framework in Niger does not define migrant entry into the labour market by a quota system or a labour market test (United Nations, 2015). Most unskilled labourers in Niger are part of the informal economy, especially in the agricultural, artisanal, and construction sectors which, in most instances, are unregulated and workers are subject to poor labour practices (US Department of Commerce, 2017). Migrant women are employed in the domestic work and the hospitality sectors which, for cultural reasons, do not employ Niger women (United Nations, 2015). However, high-skilled labour migrants are employed in the energy sector (ibid). Because of the extreme poverty rate in the country (52.0% in 2023), as indicated by the World Bank (2024), labour migrants in Niger are predominantly involved in the informal economy where they create opportunities for themselves.

HUMAN TRAFFICKING

HUMAN TRAFFICKING

The government of Niger does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking, but it is making significant efforts to do so (US Department of State, 2022). Niger is considered a Tier 2 country owing to increased efforts demonstrated by government officials to investigate and prosecute more suspected traffickers and identify more victims (ibid). The government also increased funding to the National Coordinating Commission for the Fight against Trafficking in Persons (CNCLTP) and to the National Agency for the Fight against Trafficking in Persons and the Illicit Transport of Migrants (ANLTP/TIM) (ibid). According to a US Department of State (2020) report, a shelter for trafficking victims was opened and staffed by the national government, the first of its kind in the country.

Despite being a landlocked country, Niger is still a departure, transit, and destination point for victims of human trafficking and migrant smuggling (UNODC, 2020). Niger is a transit country for men, women, and children from West and Central Africa through Algeria, Libya, and Morocco to Western Europe. Nigerien authorities claimed to have made the fight against human trafficking a government priority, but many officials still do not know enough about the trafficking and smuggling of migrants (ibid). Human traffickers exploit both domestic and foreign victims in Niger and exploit victims from Niger abroad (US Department of State, 2022). Traditionally, traffickers in Niger have primarily exploited Nigerien as well as West and Central African women and children in sex and labour trafficking (ibid). Nigerien children are forced to labour in the country’s gold, salt, trona, and gypsum mines and in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors, and to beg in markets and at bus stations (ibid). Girls and women are sex trafficked along the border with Nigeria, with many Nigerian women becoming victims of human trafficking during their transit through Niger to North Africa (ibid).

In 2022, the government investigated 53 suspects in an unspecified number of cases, prosecuted 49 alleged traffickers, and obtained convictions for three traffickers. The transition government in 2023 reported investigating 35 suspects in 26 cases (17 for sex trafficking and 18 for labour trafficking), initiated prosecution of 17 alleged sex traffickers and obtained convictions of 10 traffickers (four sex trafficking and six labour trafficking) (US Department of State, 2024). Although the transition government initiated fewer investigations from 2023, it successfully prosecuted and obtained convictions of more traffickers than the previous government.

REMITTANCES, RETURNS AND RETURNEES

REMITTANCES, RETURNS AND RETURNEES

With more than 10 million people (41.8% of the population) living in extreme poverty and facing a declining growth rate of 5.8% in 2019, 3.6% in 2020, and below 1.5% in 2021 (World Bank, 2022), migration and remittances remain a viable way to provide financial assistance to households and support economic development in Niger. According to Oumarou (2021b), the remittance flow into Niger stood at 293 million US dollars in 2019, constituting 3% of the gross domestic product (GDP). A survey conducted in Tahoua city highlighted the contribution of remittances in supporting households as it indicated that 45.7% is used for food, 19.3% for education, 10.36% for health care, and 5.4% for house rent (Oumarou, 2021a). Also, remittance flow provides start-up capital for small businesses that creates employment opportunities within communities in Niger (IOM, 2021a). The Nigerien government recognises the importance of remittance contribution to the development of its economy and it is taking practical steps to help protect its migrant workers abroad. For example, in 2021, Libya and Niger signed a memorandum of understanding on labour migration between the two countries (IOM, 2021b). Remittance flow therefore constitutes an important source of livelihood at the household level and also a source of income generation and employment at the community and national levels.

Since 2019, IOM Niger has facilitated the return of over 66,619 people originating from 30 African countries to their countries of origin, positioning Niger as the leading country of voluntary returnees (IOM, 2024). Most of the returnees are from Libya and Algeria, and they are accommodated in five transit centres located in Arlit, Dirkou, Agadez, and Niamey. The transit centres offer essential services such as shelter, health care, water, psychosocial support, legal assistance, liaison with consular representatives for travel documents, and voluntary return to their country of origin (ibid). Niger is therefore considered a transit country for returning migrants as it provides a humanitarian corridor for the safe passage of returnees or nationals of other countries passing through the country. With regard to Nigerien returnees, most of them are assisted by international organisations to reintegrate within their host communities. For example, to help ensure sustainable reintegration through economic self-sufficiency and social stability of returning Niger migrants from Libya and Algeria, the IOM partners with local NGOs to provide training, equipment, and cattle to returnees in the areas of Tillabéri, Tahoua, Zinder, and Maradi (IOM, 2020b). Despite making known its intention not to be part of the regional ECOWAS bloc, the centrality of Niger destines that it will play a central role in facilitating the return of migrants within the region.

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

Core international organisations that have drastically increased their presence in Niger in recent times are the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). The IOM works with the government of Niger and other relevant partners on the implementation of the anti-smuggling law, the development of an action plan to combat smuggling, and the provision of training to law enforcement and the judiciary. The IOM also provides the government and its branches and agencies with capacity-building skills and expertise in the various fields of migration. To support the government with the development of a comprehensive national strategy on migration, the IOM collects and analyses data on migration through profiling, provides counselling and direct assistance, and helps with voluntary return to countries of origin. The IOM works in the entire ECOWAS region, promoting regional cross-border cooperation and increased coordination and information exchange between border agencies. They have established five open-type transit centres for migrants in Arlit, Dirkou, Agadez, and Niamey. Accommodation is voluntary, with the main condition for accommodation being a willingness to voluntarily return home.

The UNHCR operation in Niger is managed by 416 staff in eight different locations. While the UNHCR continues to focus on delivering aid to those most in need, the organisation is becoming more involved with the government and other relevant stakeholders to improve collaboration. Owing to rising insecurity along the borders of Niger, the number of internally displaced persons has risen sharply. With the support of the European Union, the UNHCR constructed 2,164 social houses for the most vulnerable refugees and Nigeriens in the Diffa region. The UNHCR and the government of Niger have worked together to develop a joint strategy to close camps in the Tillabéri region in order to support the socio-economic integration of Malian refugees into the country. The UNHCR also manages multiple refugee camps and is strongly engaged with the government of Niger, NGO partners, and the World Bank to create development-oriented interventions and foster economic recovery and long-term solutions through urbanisation and the construction of sustainable housing.

Floodlist. 2022. Niger – 168 dead, 227,000 affected as flooding continues. Retrieved from: https://floodlist.com/africa/niger-floods-september-2022

Idrissa, A. 2019. Dialogue in divergence: The impact of EU migration policy on West African integration: The cases of Nigeria, Mali, and Niger. Leiden University: Friedrich Ebert Stiflung. Retrieved from: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/15284.pdf

Index Mundi. 2020. Country comparison: Population growth rate. Retrieved from: https://www.indexmundi.com/g/r.aspx?v=24

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2022. Country profile: Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/niger/

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2024. Country profile: Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/niger/

International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). 2015. A survey on migration policies in West Africa. Vienna: International Centre for Migration Policy Development.

International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). 2022. Migration outlook 2022: West Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.icmpd.org/file/download/57218/file/ICMPD_Migration_Outlook_WestAfrica_2022.pdf

International Centre for Migration Policy and Development (ICMPD) & International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2015. A survey on migration policies in West Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/2018-09/survey_west_africa_en.pdf

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2023. Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/integration/themes/mdw/map/countries/WCMS_170055/lang--en/index.htm

International Republican Institute (IRI). 2020. Migration and governance in Niger: A critical juncture. Retrieved from: https://www.iri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/niger_migration.041320.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2016. Niger; 2016 migrant profiling report. Retrieved from: https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/1406718.html

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. IOM opens new transit centre for unaccompanied migrant children in Niamey. Retrieved from: https://rodakar.iom.int/news/iom-opens-new-transit-center-unaccompanied-migrant-children-niamey

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020a. Migration trends from, to and within the Niger. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iom-niger-four-year-report.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020b. IOM Niger: assisted voluntary return for stranded Malian; over 1,400 remain in transit centres. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/news/coronavirus/iom-niger-assisted-voluntary-return-stranded-malians-over-1400-remain-transit-centers

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020c. New reintegration projects for more than 1,000 community members and returnees in Niger. Retrieved from: https://rodakar.iom.int/news/new-reintegration-projects-more-1000-community-members-and-returnees-niger

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020d. Direct assistance to migrants in transit centres. Retrieved from: https://rodakar.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl696/files/documents/Infosheet%2520Transit%2520Centres%2520EN.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2021a. IOM Niger study shows significant socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on migrant families in communities of origin. Retrieved from: https://niger.iom.int/news/iom-niger-study-shows-significant-socio-economic-impact-covid-19-migrant-families-communities-origin

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2021b. Libya and Niger move forward on strengthening migration management and labour mobility. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/news/libya-and-niger-move-forward-strengthening-migration-management-and-labour-mobility

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2024. Niger main host country for voluntary return worldwide with 66,700 vulnerable migrants returned to their countries of origin. Retrieved from: https://rodakar.iom.int/news/niger-main-host-country-voluntary-return-worldwide-66700-vulnerable-migrants-returned-their-countries-origin-2019

Jegen, L. 2020. The political economy of migration governance in Niger. Arnold Bergstraesser Institut. Retrieved from: https://www.arnold-bergstraesser.de/sites/default/files/medam_niger_jegen.pdf

Migration Data Portal. 2021. Profile: Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/

Oumarou, I. 2021a. Remittance in Niger: Effects on economic growth and on migrants’ left behind. Croatian Review of Economic Business and Social Statistics, 7(1):60-69. Retrieved from DOI:10.2478/crebss-2021-0005

Oumarou, I. 2021b. Remittances and economic growth in Niger: An error correction mechanism approach. Journal of Social and Economic Statistics, 10(1-2):17-29. Retrieved from: https://intapi.sciendo.com/pdf/10.2478/jses-2021-0002

Turner, D. & Teague, S. 2019. Trans-Saharan labour emigration from Niger: Local governance as mediator of its underlying causes and consequences. Swedish International Centre for Local Democracy. Retrieved from: https://www.local2030.org/library/606/Trans-Saharan-labour-emigration-from-Niger-Local-governance-as-mediator-of-its-underlying-causes-and-consequences.pdf

UN Women Niger. 2021. The gendered impact of migration in Niger. Retrieved from: https://africa.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2021/12/factsheet-the-gendered-impacts-of-migration-in-niger

United Nations (UN). 2015. A survey on migration policies in West Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/events/other/workshop/2015/docs/Workshop2015_Niger_Migration_Fact_Sheet.pdf

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2018. Migrant children expelled to Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/niger/press-releases/migrant-children-expelled-niger

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2019. Protecting children on the move in Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/niger/media/2991/file/ISSUE%20BRIEF:%20Children%20on%20the%20Move%20in%20Niger%202020.pdf

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2023. Human development insights. Retrieved from: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. Refugees and asylum seekers in Agadez. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/fr/documents/download/88417#:~:text=89%25%20of%20the%20population%20under,under%20the%20age%20of%20eighteen.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2021. Niger. Retrieved from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/Niger-Factsheet-October-2021.pdf

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Niger: Population of concern. Retrieved from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/niger

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024a. Niger. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/ner

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024b. Niger: Refugee policy review framework country summary as at 30 June 2023. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/niger/niger-refugee-policy-review-framework-country-summary-30-june-2023-update-summary-30-june-2023

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2020. Taking action against human trafficking and migrant smuggling in Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/glo-act4/News/taking-action-against-human-trafficking-and-migrant-smuggling-in-niger.html

US Department of Commerce. 2017. Niger – 9.2-Labour policies & practices. Retrieved from: https://legacy.export.gov/article?id=Niger-Labor-Policies-Practices

US Department of State. 2020. Trafficking in Persons Report: Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-trafficking-in-persons-report/niger/

US Department of State. 2022. Trafficking In Persons Report: Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/niger/

US Department of State. 2024 Trafficking in Persons Report: Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/niger/

World Bank. 2022. The World Bank in Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/niger/overview

World Bank. 2024. The World Bank in Niger. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/niger/overview