Historical Background

Historical Background

From the 1950s to contemporary Kenya, there have been four waves of migration that shaped the migration pattern in Kenya. From 1950 to 1960 a small number of Kenyans emigrated to the United Kingdom and the United States specifically through scholarship programmes sponsored by international organisations. This was to acquire skills that were lacking in Kenya in preparation for independence (Chadalavada, 2024). Post-independence, the process of acquiring skills was enhanced and continued through government sponsorship by the first democratically elected president of Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta, who also studied abroad (Ibid).

The second wave of migration took place during the 1970s and 1980s with the government continuing its funding programme for Kenyans abroad to acquire skills for the social, economic and structural development of the country (Ibid). Due to the contemporaneous tightened immigration policy of the United Kingdom and the United States and inadequate government funding, India became a preferred destination for Kenyans willing to study abroad. By the late 1980s against the backdrop of a declining economy, the acquisition of skills for the development of Kenya was no longer an emigration driver. During this period, Kenyans emigrated to escape political, economic and ethnic unrest (Ibid).

The third wave of migration took place during the 1990s and early 2000s which saw Kenyans moving to other African countries and the Middle East in search of better opportunities. This phase saw Kenyans of all skills emigrating.

Similarly, the fourth wave (contemporary) of emigration from Kenya continues the brain drain, specifically in the medical sector with trained doctors and nurses emigrating to the US, UK, Canada, and Australia (Ibid). students are emigrating to acquire skills without the aim of returning home to develop the country. In most cases, they apply for permanent residence after the completion of their studies.

Also, because of its centrality, economic prioress, and relative political stability in the sub-region, Kenya remains an attraction for migrants fleeing economic hardship and political persecution from their countries, such as South Sudan. Kenya is host to two of the largest refugee camps in the world, the Kakuma refugee camp and the Dadaab refugee complex which is host to an estimated population of more than 600,000 refugees and asylum seekers (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2023 & UNHCR and the Government of Kenya, 2024). The country is also an important transit route for many migrants who are heading to South Africa which is one of the biggest economies in the continent in search of opportunities.

Migration Policies

Migration Policies

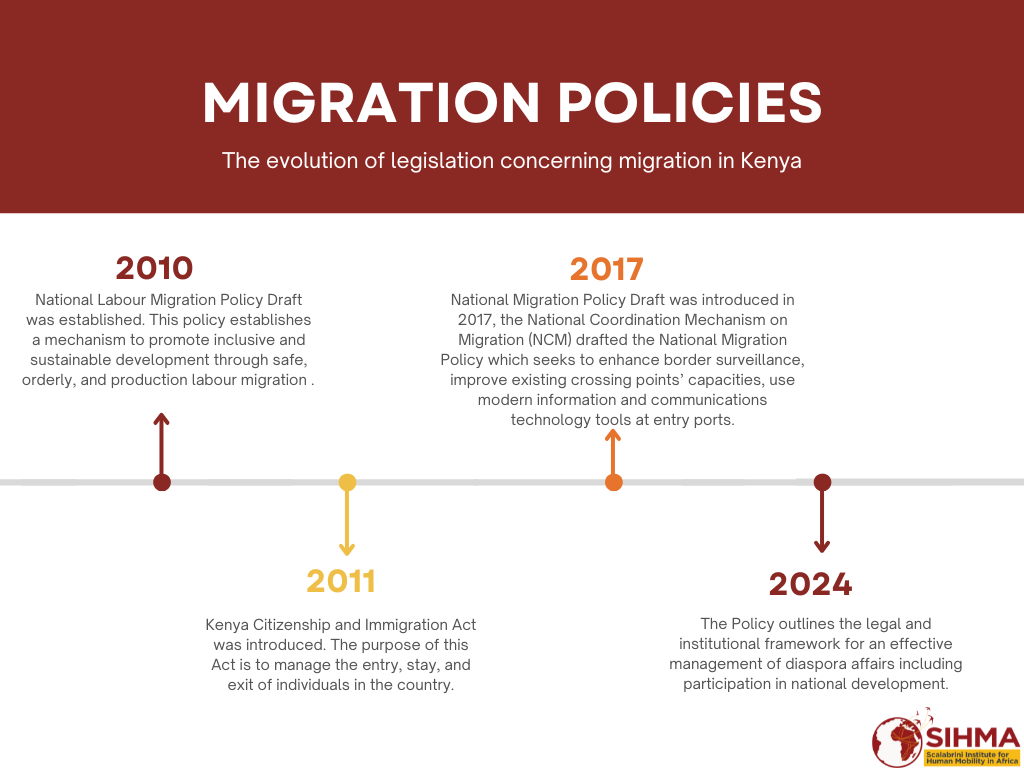

There are several migration-related policy frameworks in Kenya including the Kenya Citizenship and Immigration Act, the National Migration Policy Draft, Kenya Vision 2030, the National Labour Migration Policy Draft, and the National Diaspora Policy Draft (International Organisation of Migration (IOM), 2018). The Kenya Vision 2030 is the Kenyan government’s national planning strategy document, and it makes minor references to migration and has three pillars, social, economic and political (Ibid). The document highlights various legal frameworks and sets out the efforts required to mobilize the Kenyan diaspora for development considering diaspora remittances as one of the flagship projects under the financial sector (Ibid). The table below summarizes some of the different policy frameworks in Kenya.

Table 1: Migration Policies in Kenya

Source: IOM, 2022a & Republic of Kenya, 2024

Two key policy frameworks govern migration policies in Kenya which are the Kenyan National Migration Policy and the Kenya Diaspora Policy. The Kenya National Migration Policy was informed by the African Union Lusaka Council of Ministers’ decision in July 2001 that laid a foundation for migration policy frameworks (IOM, 2018). The National Migration Policy covers issues related to citizenship, labour migration and return, trafficking in persons, refugee movements, border management and the protection of Kenyans living abroad. Also, the policy aims to address the management and development of international migration and the efficient delivery of migration services. Its framework focuses on key thematic areas including migration and security; migration and development; facilitation of international mobility; forced migration; cross-cutting issues in migration; national coordination and international cooperation; and migration data, information management, and capacity-building (IOM, 2018). On the other hand, the Kenya Diaspora Policy seeks to mobilize the diaspora into the development process of the country.

Other relevant legislation includes the Refuge Act 2006 and the Counter-Trafficking in Person Act 2010. The main legislation governing refugees and asylum seekers is the Refugee Act 2006, which outlines the criteria for disqualification, exclusion, recognition, cessation, withdrawal, and cancellation of refugee status. Additionally, it provides for various identification documents for refugees and asylum seekers and spells out their rights and duties. The Act is effected through the Refugee Affairs Secretariat, the Refugee Affairs Committee, the Commissioner for Refugee Affairs, Camp Officers, and the Refugees Appeal Board (IOM, 2018). Also, the Refugee Act 2021 seeks to promote refugee self-reliance by enhancing the protection space for asylum seekers and refugees, supporting immediate and ongoing needs for asylum seekers, refugees and host communities, and promoting regional cooperation and international responsibility sharing in the realisation of durable solutions for refugees (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), 2021).

Timeline of Migration Policies in Kenya. Source: SIHMA

The Counter-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2010, specifies punishments for those involved in crimes, such as the promotion of trafficking, the acquisition of travel documents by fraud or misrepresentation, and the facilitation of entry into or exit from Kenya. Additionally, it provides protection for victims of such crimes (IOM, 2018). The legislation is based on the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. Before this act, trafficking cases were judged under the Penal Code, Children’s Act (2001) and the Sexual Offenses Act (2006).

Due to the multi-faceted components of mixed migration, there have been difficulties in implementing some of the migration-related legislation, for example, the Refugee Act of 2006. There seems to be a failure by law enforcement officers to distinguish between irregular migrants, asylum seekers and criminals, thus leading to ineffective application of the refugee law and increased levels of abuse, extortion, and harassment of refugees (Danish Refugee Council, 2016). Once entering Kenya, asylum seekers have a period of 30 days after entering the country to get to a registration point, usually in a refugee camp. Despite this legal stipulation, asylum seekers tend to go to urban centres. This blurs the time of arrival. According to the Danish Refugee Council (2016), officials conducting interviews do not understand refugee law sufficiently to be able to classify travellers as either migrants or asylum seekers correctly. This confusion is compounded by language barriers. The same applies to trafficking legislation: the confusion of the Counter-Trafficking Act with Section 14 of the Sexual Offence Act results in trafficked children being persecuted and punished as child sex tourists (IOM, 2018).

Although a government-led inter-agency coordination platform named the National Coordination Mechanism on Migration was formed in 2016 with efforts to implement the African Migration Policy Framework and to establish a coherent manner of handling migration issues regionally and nationally, several gaps need to be addressed concerning migration policy framework in Kenya. One of the key gaps that need to be addressed is around the implementation of the existing laws adequately. Government officials should be properly trained to understand the law. Also, the mixed nature of migration in Kenya speaks to the broader regional problems that require regional cooperation in protection, prosecution, and prevention efforts. Furthermore, there is a need for the finalisation of the draft policy frameworks as it will give the government a comprehensive direction on the management of migration in the country.

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

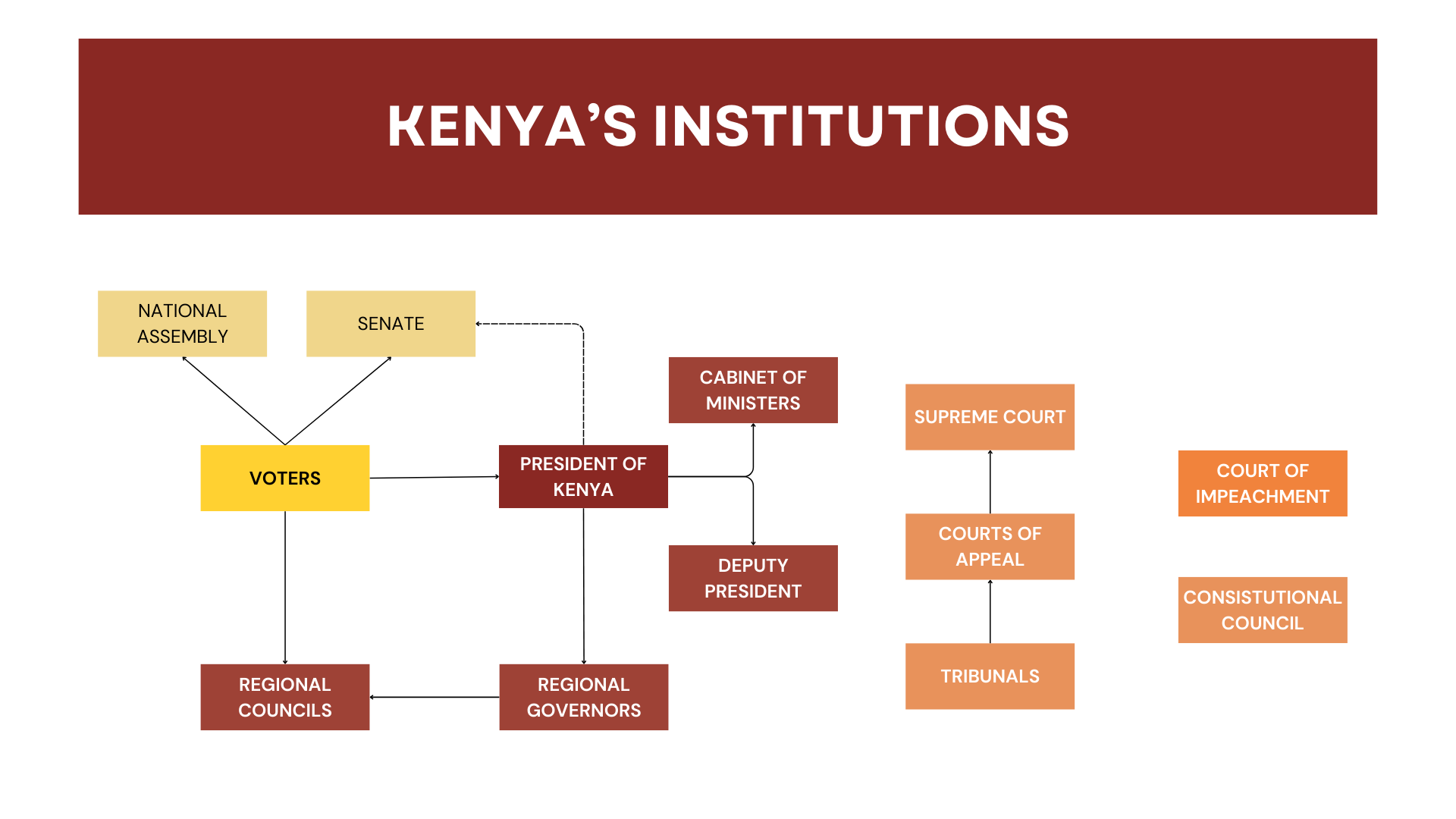

Actors in the field of migration include the Ministry of Interior and Coordination of National Government (including Directorate/Department of Immigration Services), the Ministry of Labour, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Social Security and Services, the Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure, The Central Bank of Kenya, and Counter-Trafficking in Persons Advisory Committee (Maastricht University, 2017). The Ministry of Interior and Coordination of National Government, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Trade all partner with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Kenya's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

The core responsibilities of the Ministry of Interior and Coordination, Department of Immigration Services relate directly to people on the move and include registration of persons, births, and deaths, providing immigration services, management of refugees, border management, and maintenance of the integrated population registration system (Department of Immigration Service, 2019). The department is also the base for the National Migration Coordination Mechanism, which is a government-led inter-agency coordination platform, which is responsible for national migration management (IOM, 2016).

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

Several factors account for the patterns and the flow of internal migration in Kenya during colonial and post-colonial eras which include land disposition in the colonial era, the establishment of “native reserves” and the creation of wage labour. In the current political dispensation, despite the dismantling of the native reserves which were the supplier of labour in the colonial era, the establishment of a wage labour system creates patterns of internal migration which are similar to those during the the colonial era – predominantly rural-urban migration patterns.

However, faced with the challenges of urban life which include low wages and the high cost of living, urban migrants return to rural or less urbanised areas with lower cost of living to take on agriculture and other rural economic activities (Okumu & Moenga, 2021). According to the National Council for Population and Development (2021), drawing from the 2019 census data, several push/pull factors contribute to contemporary internal migration in Kenya including push factors like frequent instances of insecurity, droughts, floods, lack of land, pasture, infrastructure, employment, and educational opportunities, and pull factors like security, availability of land, pasture, security, water, employment, and educational opportunities.

The ten top counties with positive net migration in 2019 were the urban areas: Nairobi (230,027), Kiambu (174,176), Kajiado (100,733), Nakuru (82,054), Mombasa (73,620), Uasin Gishu (55,339), Narok (19,238), Laikipia (10,440), Kirinyaga (7,175), and Lamu (7,083) (Ibid). This is an indication that the wage labour system created during the colonial era has been reinforced within contemporary Kenya society with the development of urban areas and the negation of the rural areas.

Although most of the youthful population which constitutes a greater proportion of those who migrate resides in rural areas (32.73 million (68.9%)), there is an increasing rate of youthful (aged 20-24 years) rural-urban migration with an annual migration rate of 277,000 between 2015 and 2020 (The Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA), 2023). This pattern of youthful mobility not only causes skills development gaps but also creates shortages in manpower in rural communities whose economic backbone is in the labour-intensive agricultural sector.

Internally Displaced Persons

Internally Displaced Persons

Although conflict and violence still contribute enormously to internal displacement in Kenya, recently, disaster-related displacements are the main source of internal displacement in the country. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), (2023), between 2008 – 2023, there were 514,000 conflict and violence-related internal displacements and 2.4 million disaster-related internal displacements and 81 disaster events reported in Kenya.

Conflict

Conflict

Despite the relative peace that the country enjoys, conflict and violence still contribute to internal displacement in Kenya. Triggers of conflict and violence in Kenya include post-election violence (rooted in ethnic politics), terrorism, and scarcity of resources. For example, the post-election violence of 2007/2008 displaced 650,000 people (Wilson Center, 2022). Recently, according to the IDMC (2023), there were 40,000 conflict and violence-related displaced people by the end of 2023, of which 7,700 were displaced in 2023. Most of the recent conflict and violence-induced displacement are caused by several factors including scarcity of resources, and intercommunal conflict. For example, the conflict between Pokot and Turkana pastoralist communities over scarce resources (water, land, and pasture) has led to the displacement of thousands of community members (Shalom-Center for Conflict Resolution & Reconciliation (SCRR), 2020).

Disaster

Disaster

Natural disasters, for example, hailstorms, floods, and landslides are some of the main contributors to internal displacement in Kenya. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) (2023), in 2023, there were 641,000 disaster-induced displaced people in Kenya. According to the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) (2024a) & OCHA (2024b), as of the 3rd of May 194,305, people were displaced due to persistent heavy rains and floodings in several counties including Nakuru, Machakos, Kirinyaga, Kisumu, Homa Bay, Narok, West Pokot, Nyeri, Siaya and Tana River and by the 9 of May, the number had risen to 281,835 people.

The adverse effects of Displacement, both conflict and violence and disaster are far-reaching. In addition to the loss of lives, displacement disrupts socio-economic activities and livelihood systems. In a country where an estimated 4.4 million people are facing food insecurity (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), 2024), conflict and violence and disaster only compound the already deplorable situation and create more tension and animosity among community members.

Immigration

Immigration

As the largest economy in East Africa (Global Edge, 2024), Kenya is considered a significant migration hub for economic migrants: the location is strategic in the Horn of Africa. The country also serves as a transit point for irregular migrants travelling South to South Africa and other parts of the world including Saudi Arabia (Expertise France, 2017). According to UN DESA as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), the number of international migrants in Kenya rose from 954,900 in 2010 to 1.1 million in 2015 and remained unchanged (1.1 million) in 2020. Although in relative terms, the number of international migrants has not declined from 2010 to 2020, it has declined as a percentage of the population from 2.4% in 2015 to 2% in 2020 (Ibid). The decline can be attributed to several factors including the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy and the restriction of movement.

According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by IOM (2022), the top 5 countries of origin of international migrants in Kenya are Somalia, Uganda, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the United Republic of Tanzania with an almost equal male to female ratio (50% each). With the implementation of a visa-free regime for all Africans wishing to travel to Kenya by the end of 2023, it is expected that the number of migrants from other African countries will increase. However, the implementation of the visa-free regime for all Africans has been met with mixed feelings as the requirement of the payment of a $30 travel authorization fee can impede the movement of nationals of some African countries (for example, Malawi), who enjoyed free movement without a fee in the past (Africanews, 2024). The idea of opening the country’s borders to all African countries is in sync with the Pan-Africanism ideology and sets a good example for other African countries to emulate if Pan-Africanism can be regarded as a solution to regional conflict and tension.

Female Migration

Female Migration

According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), the male-to-female ratio of international migrants in Kenya from 2005 to 2010 increased by 2.3% and declined by 0.5% between 2015 and 2020. Although the male-to-female ratio of international migrants experienced an increase only between 2005 (48.2%) – 2010 (50.5%), there has been a steady increase in the number of female migrants in Kenya from 2005 to 2015. The Migration Data Portal states that in 2005 the stock of female migrants in the country stood at 373,000 and increased to 481,800 in 2010 and 564,000 in 2015.

However, it experienced a slight decline in 2020 when it dropped to 520,200 (Ibid). The increasing number of female immigrants in Kenya is a reflection of the current trends of feminization of migration in the region with more women (50.4%) migrating than men (IOM, 2022b) This is a reflection of the increased role that women are taking in the global economy in terms of providing for themselves, their families, and contributing to the economy.

Children

Children

Kenya is one of the top 10 countries in Africa that hosts migrant children. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), (2019), Kenya is ranked as the fifth in Africa that hosts the largest number of international migrants under 18 years. According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), in 2005, of the 773,400 immigrants residing in the country, 26.9% (231,247) of them were children 18 years and younger. In 2010, of the 954,900 immigrants residing in the country, 29.1% (277,876) of them were children, and in 2015 and 2020, of the 1.1 million immigrants in Kenya in mid-year 2015 and 2020, 31.3% (313,031) and 28.3% (283,028) respectively were children 18 years and younger (Ibid). Except for 2020 when the number of child migrants dropped, it experienced a steady increase from 2005 to 2015.

Although section 190 (1) of the Children Act of 2012 stipulates that no child shall be ordered to imprisonment or to be placed in a detention camp, the police often detain migrants and their children for alleged offences committed by their parents (Refugee Consortium of Kenya (RCK), nd). Also, although Article 43 of the constitution of Kenya provides that everyone, including migrant children, has the right to the highest attainable standard of health, housing, clean and safe water, social security, education, and to be free from hunger. Its implementation is not fully realized as access to these services is still a challenge even for citizens. Imagine the challenges for migrants. For example, although in 2008, Kenya adopted Vision 2030 which identified access to housing as a cornerstone of inclusive growth, according to Habitat for Humanity (2023), there are currently more than 4 million Kenyans living in slums with their children.

Refugees and Asylum seekers

Refugees and Asylum seekers

Hosting an estimated 744,747 registered refugees and asylum seekers by the end of February 2024, Kenya remains one of the top refugee-hosting countries in Africa (UNHCR & Government of Kenya, 2024). More than half of the refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya are from Somalia (55.8%). According to UNHCR & Government of Kenya (2024), the top origin countries of refuge and asylum seekers in Kenya are Somalia 415,761, South Sudan (175,510), the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (59,392), Ethiopia (38,207), Burundi (31,912), Sudan (12,468), Uganda (3,813), Eritrea (3,495), Rwanda (2,922), and others (1,267) (Ibid).

Although Kenya has an encampment policy, some refugees are in urban areas. The two main refugee camps in Kenya are the Daadab which includes the Hagaera, Dagahaley, and Ifo refugee camps, hosting an estimated 364,432 refugees and asylum seekers, and the Kakuma refugee camp which includes the Kalobeyei Integrated Settlement, hosting an estimated 279,452 refugee and asylum seekers (UNHCR & Government of Kenya, 2024; UNHCR, 2023). Together these camps are two of the largest in the world (Ibid). These figures do not include the profiled 16,785 individuals awaiting registration in the Dadaab refugee camp.

According to UNHCR & Government of Kenya (2024), there are an estimated 100,863 who live in urban areas, particularly, in Nairobi. Urban areas are more developed and have more opportunities than the less developed rural areas. While urban refugees often do not benefit from services provided by international organisations (for example, UNHCR) like food supply, accommodation, and medication, refugees and asylum seekers in the camps do. However, refugees and asylum seekers in the camps and settlements are challenged with overcrowding which has strained the camps' resources causing scarcity in medicine, food supply, and clean water (UNHCR, 2023).

Some of the common challenges that confront refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya include the threat of arrest, detention, harassment, extorsion, vulnerability to sexual and gender-based violence, human smuggling, and trafficking (UNHCR & World Bank, 2021). However, the state’s positive narrative of refugees and asylum seekers as contributors to the country’s economic growth and the enforcement of pro-refugee projects, like the Ushirika Plan, that provide opportunities for refugees and community members are two programmes that can foster social cohesion within communities (Institute for Security Studies (ISS), 2024). Because of the relative political stability that the country enjoys in the sub-region and the recurrent political instability in neighbouring Somalia and South Sudan, Kenya remains a “safe haven” in the region for thousands who are fleeing from war-torn zones.

Emigration

Emigration

A large portion of African migrants reside in Kenya. According to William (2016), the ratification of the Africa Migration Policy Framework has shaped the emigration flow from 1960 to 2000. The table below indicates that while there has been a fluctuation in the total number of emigrants from Kenya between 1960 – 2000, there has been a steady increase in the total number of Kenyan emigrants in other African countries.

Table 2: Emigrants from Kenya (1960 – 2000)

Source: William (2016)

However, like elsewhere in the continent, the socioeconomic and political crisis compounded by the Structural Adjustment Programme and the neo-liberal policies of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund which placed stringent measures on African countries in accessing funds redirected the flow of Kenyan emigrants from the global south to the global north (Momasoh, 2023). This is because these policies placed stringent measures on African countries in accessing funds. According to IOM (2022), between 2016 and 2020, there were 535,000 international migrants from Kenya, 47% (253,000) were male and 53% (282,000) were female. This highlights the feminization of migration (See section on female migration). The table below indicates that more than 50% of the total emigration stock from Kenya is located in the global north and such movement can be accounted for by several factors which include state fragility and livelihood failures.

Table 3: Top Ten Countries for Kenyan Emigrants

Source: IOM (2022)

Unlike in the past when a large proportion of Kenyan emigrants were moving to other African countries, recently, from 2016 to 2020 as indicated in the table above, a large proportion of Kenyan emigrants are migrating to the global north.

Labour Migration

Labour Migration

As the largest economy in the sub-region (Esat Africa), Kenya remains a pull force to millions of people, from within the sub-region (Somalia, Ethiopia, and Uganda) and beyond the region (India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan) who are seeking better opportunities.

Compared to other countries within the region, Kenya seems to have a more advanced migration policy that seeks to protect the rights of migrant workers. There are several legal agreements to which Kenya is a party that allows or seeks to relax regular labour mobility between its member states. Some of these legal agreements include:

- The International Labour Convention (ILO),

- The East African Community Common Market Protocol (EAC-CMP),

- The Common Market for East and Southern Africa (COMESA), and

- The Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD).

According to the Federation of Kenya Employers (2022a), although Kenya has developed a National Labour Migration Policy, its implementation has been stalled because it has not been adopted by the government. As a result, labour migration in Kenya is governed by Kenya’s national labour laws and policies, including:

- The National Employment Policy and Strategy, Immigration and Citizenship Act, 2011,

- Counter-Trafficking in Person Act, 2010,

- National Employment Act, 2016,

- Employment Act, 2007,

- Labour Institutions Act, 2007, and

- The Labour Relations Act, 2007.

The fragmented nature of the different pieces of legislation pertaining to labour migration undermines its effective implementation. It is therefore imperative for the National Labour Migration Policy to be promulgated into law. This would provide a comprehensive legal framework document that seeks to amongst other things enhance the coordination of labour migration governance, protect the rights of migrant workers, and provide a framework for the collection, analysis, and use of data and information on labour migration.

Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking

Kenya is ranked Tier 2 in the Trafficking in Person (2023) TIP Report as the government of Kenya does not meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking - although, in recent years, it has made some significant efforts which include the implementation of the Counter Trafficking in Person Act, 2020, the operationalisation of the National Assistance Trust Fund for Victims of Trafficking and the development of a National Referral Mechanism for assisting victims of human trafficking (Kenya News Agency, 2021). However, corruption amongst some law enforcement officials negatively impacts the government's fight against human trafficking in the country (US Department of State, 2023). Kenya remains a source, transit, and destination for children and women subjected to forced labour and sex trafficking.

According to the US Department of State (2023), an international NGO reported that there are an estimated, between 35,000 and 40,000 victims of human trafficking in Kenya including an estimated 19,000 child victims. Child trafficking remains a major concern in Kenya as traffickers prey on the vulnerabilities of children and their families who are in desperate search of better educational opportunities to improve or better their lives and that of their families. Most of the migrant and refugee children are victims of sex and labour trafficking. In 2022, the government identified 556 trafficking victims (275 in labour trafficking, 31 in sex trafficking, and 250 in unspecified forms of trafficking), investigated 11 cases (59 for sex trafficking, 10 for labour trafficking, and 42 for unspecified forms of trafficking), prosecuted 48 alleged traffickers (11 for sex trafficking, 3 for labour trafficking, and 34 for unspecified forms of trafficking), and the courts convicted 3 traffickers (Ibid). Out of the 556 identified victims, 24 were foreign nationals from South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda – the rest were from Kenya. The government in partnership with NGOs assist with medical care, psycho-social support, legal assistance, repatriation for foreign victims, and referral to NGO-run shelters (Ibid).

Also, there are victims of human trafficking from Kenya abroad. Some employment agencies both legal and fraudulent exploit Kenyans through bogus job opportunities available abroad, particularly in the Middle East. The government indicates that over 200,000 Kenyans are currently working in Saudi Arabia and more than half of them as domestic workers who experience conditions indicative of forced labour including excessive working hours and passport confiscation (US Department of State, 2023). Others are forced to work for cybercrime gangs and prostitution rings in Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar (Institute for Security Studies (ISS), 2023). Poverty and unemployment in Kenya and the appealing nature of some of the fake opportunities advertised online lure Kenyans into the web of traffickers (Ibid).

Remittances

Remittances

Remittance flow constitutes one of the sources of revenue flow into the economy of Kenya. According to the World Bank (2023), Kenya has experienced a steady increase in remittance flow into the country since 2009 when it stood at $631,460,883 million to $4.06 billion in 2022 (World Bank, 2024). During the COVID-19 pandemic era when most economies experienced economic slowdown which adversely affected the flow of remittances, for example, Uganda and Ghana, Kenya continued to experience an increase from $2.84 billion in 2019 to $3.11 billion in 2020 and $3.77 billion in 2021 (Ibid). According to EastAfrican (2024), in 2023 remittance flow continued to increase as it attained a record high of $6.19 billion in 2023. However, although remittance flow as a percentage of GDP experienced an increase from 2009 when it stood at 1.5% of GDP to 3.6% of GDP in 2022, it experienced a slight decrease from 2018 when it dropped from 3% of GDP to 2.8% of GDP in 2019. As of January 2024, the top 5 countries of remittance inflows to Kenya were the USA, the UK, Saudi Arabia, Germany, and Australia (Business Daily, 2024).

According to Maara, et al. (2019), in addition to its contribution to increasing the share of total household expenditure on education, consumer durables, and housing, international remittance flow has a positive effect on household spending on investment with endogeneity control. In a country where the youth unemployment rate is as high (67%) (Federation of Kenya Employers, 2022b) as in Kenya, remittance flow remains not only an important source of income but also a means to pay for skills development and investment in training.

Returns and Returnees

Returns and Returnees

The returns in Kenya can be explained in different ways. There are several push factors which drive the return of migrants from their host countries including global challenges like the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in migration policies, discrimination, marginalization, and the lack of economic opportunities. However, there are also several pull factors including political stability, and good governance which attract the return of migrants. Both forces have contributed enormously to return migration in Kenya. According to Onyango et al. (2021), the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic worsened the already vulnerable situation of labour migrants from Kenya in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries which precipitated their return home. However, returning migrants are confronted with compounded challenges including returning home “empty-handed” (that is without enough financial gains), being branded or stigmatised, and returning home to a struggling economy with very high levels of unemployment. These factors reduce the chances of employment. These social and psychosocial factors can contribute to depression. For example, some returnees in Kenya include ex-terrorist Al-Shabab fighters who are beneficiaries of the 2015 government amnesty programme which saw an estimated 1000 ex-fighters returning to their communities (Social Science Research Council (SSRC), 2022). They are confronted with reintegration challenges which include trust deficit and community acceptance.

International Organisations

International Organisations

Several regional and international organisations assist migrants. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) focuses on programmes such as immigration and border management, counter-trafficking, provision of health assistance for migrant communities, and assisting returnees with reintegration into their host communities. The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) advocates on behalf of stateless persons and supports access to documentation (birth certificates and ID cards). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) focuses on governance, peace, and social cohesion. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) is devoted to promoting social justice and internationally recognised human and labour rights, through a decent work agenda. There are several international organisations assisting refugees and asylum seekers as implementing partners with the UNHCR in Kenya which include: CARE International, Danish Refugee Council, FilmAid International, Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), International Rescue Committee, Islamic Relief, Kenya Red Cross Society, Lutheran World Federation, Norwegian Refugee Council, Peace Winds Japan, Save the Children International, Windle Trust UK in Kenya, Action Africa Help International Kenya and the Francis Xavier Project.

Africanews. 2024. Kenya faces backlash over “Hectic” visa-free entry. Retrieved from: https://www.africanews.com/2024/01/08/kenya-faces-backlash-over-hectic-visa-free-entry//.

Business Daily. 2024. Easing inflation in US, UK lifts Kenya’s diaspora dollar flows. Retrieved from: https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/economy/easing-inflation-in-us-uk-lifts-kenya-s-diaspora-dollar-flows-4538768.

Chadalavada, S. 2024. Migration and development in Kenya. Talk Diplomacy. Retrieved from: https://www.talkdiplomacy.com/post/migration-and-development-in-kenya#:~:text=Kenya's%20migration%20history%20can%20be,that%20were%20unavailable%20in%20Kenya.

CIA World Factbook. 2024. Kenya. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/kenya/.

Danish Refugee Council. 2016. Kenya Country profile. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/kenya/kenya-country-profile-updated-april-2016.

Expertise France. 2017. Kenya country statement: Addressing migrant smuggling and human trafficking. Retrieved from: https://www.expertisefrance.fr/documents/20182/234347/AMMi+-+Country+Report+-+Kenya.pdf/51146abe-92b9-456a-b05b-ddedca54208b#:~:text=As%20a%20critical%20hub%20for,traveling%20south%20toward%20South%20Africa.

Federation of Kenya Employers. 2022a. Membership briefing: Sustainable migration. Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---act_emp/documents/publication/wcms_849251.pdf.

Federation of Kenya Employers. 2022b. Youth Employment. Retrieved from: https://www.fke-kenya.org/policy-issues/youth-employment.

Global Edge. 2024. Kenya: Economy. Retrieved from: https://globaledge.msu.edu/countries/kenya/economy.

Habitat for Housing. 2023. Research on systematic barriers towards access and usage of housing finance in Kenya. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/kenya/research-systemic-barriers-towards-access-and-usage-housing-finance-kenya.

HIAS. 2021. Kenya’s Refugee Act 2021: Opportunities for refugee livelihoods and self-reliance, part 1. Retrieved from: https://hias.org/wp-content/uploads/kenyas_refugee_act_2021-_opportunities_for_refugee_livelihoods_and_self-reliance_-final_draft31.pdf.

IDMC. 2023. Country Profile: Kenya. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/kenya/.

IOM. 2016. Kenya unveils National Migration Coordination Mechanism. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/news/kenya-unveils-national-migration-coordination-mechanism.

IOM. 2018. Migration in Kenya: A country profile 2018. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-kenya-country-profile-2018.

IOM. 2022a. Republic of Kenya: Migration governance indicators. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/MGI-2nd-Kenya-2022.pdf.

IOM. 2022b. Women and girls account for majority of migrants in East and Horn of Africa: IOM report. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/news/women-and-girls-account-majority-migrants-east-and-horn-africa-iom-report.

IOM. 2022. International migration from Kenya (2016 – 2020). Retrieved from: https://kenya.iom.int/resources/international-migration/kenya-undesa-2020.

IPC. 2024. Kenya: Acute food insecurity situation February 2023 and projection for March – June 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/en/c/1156210/#:~:text=In%20the%20current%20period%2C%20it,AFI%20Phase%204%20(Emergency).

ISS. 2023. East Africa’s youth scammed by promises of overseas work. Retrieved from: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/east-africas-youth-scammed-by-promises-of-overseas-work.

ISS. 2024. Kenya and Ethiopia could show the way on migration governance. Retrieved from: https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/kenya-hosts-over-1m-foreign-migrants-iom-says-4549342.

Kenya News Agency. 2021. Government committed to fight human trafficking. Retrieved from: https://www.kenyanews.go.ke/government-committed-to-fight-human-trafficking/.

Kenya News Agency. 2019. Floods displaced over 300 people in Trans Nzoia. Retrieved from: https://www.kenyanews.go.ke/floods-displace-over-300-people-in-trans-nzoia/.

KIPPRA. 2023. Unlocking rural areas to curb rural-urban migration among youth in Kenya. Retrieved from: https://kippra.or.ke/unlocking-rural-areas-to-curb-rural-urban-migration-among-youth-in-kenya/.

Maara, N. et al. 2019. Remittance and household expenditure allocation behaviour in Kenya. African Journal of Economic Review, Vol. V11(1):85-108. Retrieved from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajer/article/view/182552/171929.

Maastricht University. 2017. Study of migration routes in the East and Horn of Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.merit.unu.edu/publications/uploads/1517475164.pdf.

Momasoh, CM. International migration and social inclusion of migrants in South Africa: The case of Cameroonian migrants in the Western Cape. University of Cape Town. Retrieved from: https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstreams/2b6f26d1-678e-42ea-ba90-cd9598918297/download.

Nation. 2024. 300 families displaced by floods in Magadi. Retrieved from: https://nation.africa/kenya/counties/kajiado/300-families-displaced-by-floods-in-magadi-4499240.

National Council for Population Development. 2021. Internal migration and development planning in Kenya: “A desk review of existing literature to inform policy and programme”. Advisory paper No. 5. Retrieved from: https://ncpd.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Advisory-Paper-5-Internal-Migration-and-Development-Planning-in-Kenya.pdf.

OCHA. 2024a. Kenya: Heavy rains and flooding update – flash update #5 (10 May 2024). Retrieved from: https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/kenya/kenya-heavy-rains-and-flooding-update-flash-update-5-10-may-2024.

OCHA. 2024b. Kenya: Heavy rains and flooding update – flash update #4 (03 May 2024). Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/kenya/kenya-heavy-rains-and-flooding-update-flash-update-4-03-may-2024.

Okumu, T. & Moenga, J. 2021. Urban-rural migration under the devolved governance system in Kenya: subsequent implications for income and occupation. Retrieved from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-124964/v2.pdf.

Onyango, L. et al. 2021. Global Fund to End Modern Slavery (GFEMS) Kenya COVID-19 situational analysis report – Overseas labour recruitment. Retrieved from: https://www.gfems.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/NORC-GFEMS-Kenya-COVID-19-Situational-Analysis-Report_OLR_.pdf.

RCK. Nd. Questionnaire of the special rapporteur on the human rights of migrants: Ending immigration detention of children and seeking adequate reception and care for them. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Migration/CallEndingImmigrationDetentionChildren/CSOs/RefugeeConsortium_of_Kenya_submission.docx.

Republic of Kenya. 2024. Kenya diaspora policy 2024. Retrieved from: https://mfa.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Draft-Diaspora-Policy-2024-13.3.2024.pdf.

Shalom-SCRR. 2020. Briefing paper No 4: An analysis of the Turkana-Pokot conflict. Retrieved from: https://shalomconflictcenter.org/briefing-paper-no-4-an-analysis-of-turkana-pokot-conflict/.

Social Science Research Council. 2022. Reintegration challenges in the post-2015 Amnesty Program for former foreign fighters. Retrieved from: https://kujenga-amani.ssrc.org/2022/04/29/reintegration-challenges-in-the-post-2015-amnesty-program-for-former-foreign-fighters-in-coastal-kenya/.

The EastAfrican. 2024. Kenya diaspora remittances up 19pc in first quarter as inflationary pressure eases. https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/kenya-diaspora-remittances-up-19pc-in-first-quarter-4591980.

The World Bank. 2024. Personal remittances, received (current US$) – Kenya. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT?locations=KE.

UNHCR & Government of Kenya. 2024. Kenya statistic package – 29 February 2024: Registered refugees and asylum-seekers. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/ke/what-we-do/reports-and-publications/kenya-operation-statistics.

UNHCR & World Bank. 2021. Results from the 2020-2021 urban socioeconomic survey. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/kenya/understanding-socio-economic-conditions-urban-refugees-kenya-results-2020-2021-urban.

UNHCR. 2016. UNHCR partners in Kenya. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/ke/144-unhcr-partners-in-kenya.html.

UNHCR. 2023. Inside the world’s five largest refugee camps. Retrieved from: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/inside-the-worlds-five-largest-refugee-camps/.

UNICEF. 2019. A snapshot of migrant and displaced children in Africa. Retrieved from: https://data.unicef.org/data-for-action/snapshot-migrant-displaced-children-africa/.

US Department of State. 2023. Trafficking in person report: Kenya. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/kenya/.

William, B. 2016. Macroeconomic determinants of emigration from Kenya. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. Retrieved from: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/77130/1/MPRA_paper_77130.pdf.