Historical background

Historical background

Because of the development of its gold mines and cocoa farms, Ghana, formerly known as the Gold Coast, attracted many migrants from surrounding regions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The number of migrants continued to grow between 1910 and 1957 when Ghana declared its independence. According to Bump (2006), this was mainly because of organized labour recruitment programmes implemented by the colonial government at the time.

After independence, the number of people migrating to Ghana far surpassed the number leaving the country, creating a positive net immigration rate. The 1960 census indicates there were 827,481 immigrants from other countries living in Ghana (12% of the population) and 98% of those immigrants were of African descent (Ibid). The Pan-Africanist political stance of Ghanaian independent leaders also attracted other African migrants to Ghana after independence (International Organisation for Migration (IOM, 2019). However, eight years after independence, because of economic and social issues such as high unemployment rates, growing levels of crime, and, later, political instability, the trend turned around. By the 1980s, Ghana had become a country of emigration, which it still is today (Bump, 2006 & Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2022).

Even though Ghana is recovering from its financial crisis compounded by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine that stifled economic growth in the last five years, the economic situation is still dire as the youth unemployment rate seats at 32.8%, a major migration push factor (International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2024 & United Nations, 2023a). On the other hand, the availability of opportunities and the existence of large diasporas in other African countries, Europe and North America continue to be important pull factors. Although Ghanaian emigrants mainly go to other African countries, often in the region, some move to Europe and North America.

Migration policies

Migration policies

Ghana is a party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, the 1967 Protocol and the OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa of 1969. Ghana is also party to the Palermo Protocol, and the protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in person, Especially Women and Children.

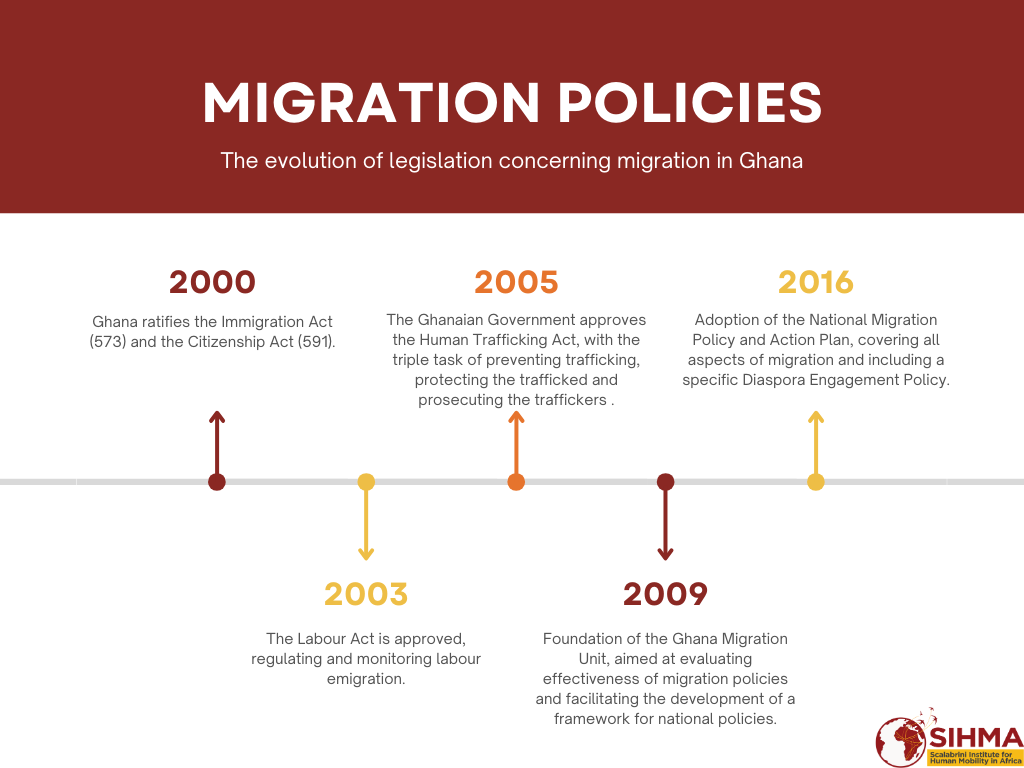

Ghana has three main pieces of migration legislation that address the legal and regulatory aspects of migration: The Immigration Act (573) of 2000, the Immigration Amendment Act (848) of 2012, and the Immigration Regulations (L.I 1691) of 2001 (International Organisation for Migration (IOM, 2018). There is also legislation in place that regulates and monitors labour emigration, to prohibit the recruitment of employees outside of Ghana without the proper documentation, this is achieved through the Labour Act 2003 and Labour Regulation 2007. In 2009, the Ghana Migration Unit was founded to evaluate the effectiveness of migration policies and more importantly facilitate the development of a framework for national policies. Before the Ghana Migration Unit, the country did not have a national migration policy in place, thus with the help of the Ministry of Interior, the Inter-Ministerial Steering Committee was set up to draft a national migration policy (International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), 2017). In 2016, the National Migration Policy for Ghana was published, which serves as the country’s official migration strategy document.

Timeline of Migration Policies in Ghana. Source: SIHMA

Concerning refugees and asylum seekers, in 1993, the country was at its peak when it provided refuge to over 150,000 persons (Bump, 2006). Because of this, the government passed legislation creating a Refugee Board to deal with refugee policy. In practice, UNHCR and private citizen groups provide material support to refugee groups (Bump, 2006). According to an article on the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) website, Ghana has very progressive legislation concerning refugees and asylum seekers (UNHCR, 2019). It allows privileges to all citizens in terms of a supportive enabling environment and access to services, including asylum seekers and refugees by permitting them to choose where to live, move freely, establish a livelihood, and acquire a travel document (Ibid). However, the framing of the legislation does not make provision for the integration of migrants into the communities. For example, the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre Act, 2013, reserves certain jobs only for Ghanaians, including the sale of goods or provision of services in a market, petty trading or hawking, or selling of goods in a stall at any place, the operation of a beauty salon or barber shop or the minimum requirement of two hundred thousand USD for a joint investment venture (See section 27 and 28 of the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre Act, 2013). These are policies that not only asphyxiate the integration process of migrants but also limit competition and economic growth of the country.

Ghana has a Human Trafficking Act, which was enacted in 2005. It comprises three components of counter-trafficking: prevention of human trafficking, protection of trafficked persons and prosecution of traffickers (Sertich & Heemskerk, 2011). According to Sertich & Heemskerk (2011), two attorneys who have researched the implementation of the Ghanaian Human Trafficking Act, posit that the government has been successful in implementing the Act’s preventive strategies and has demonstrated the ability to prosecute both domestic and international human trafficking cases. The Ghanaian government has however not managed the protective duties mandated by the Act, particularly in providing shelter for trafficked persons (Ibid).

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

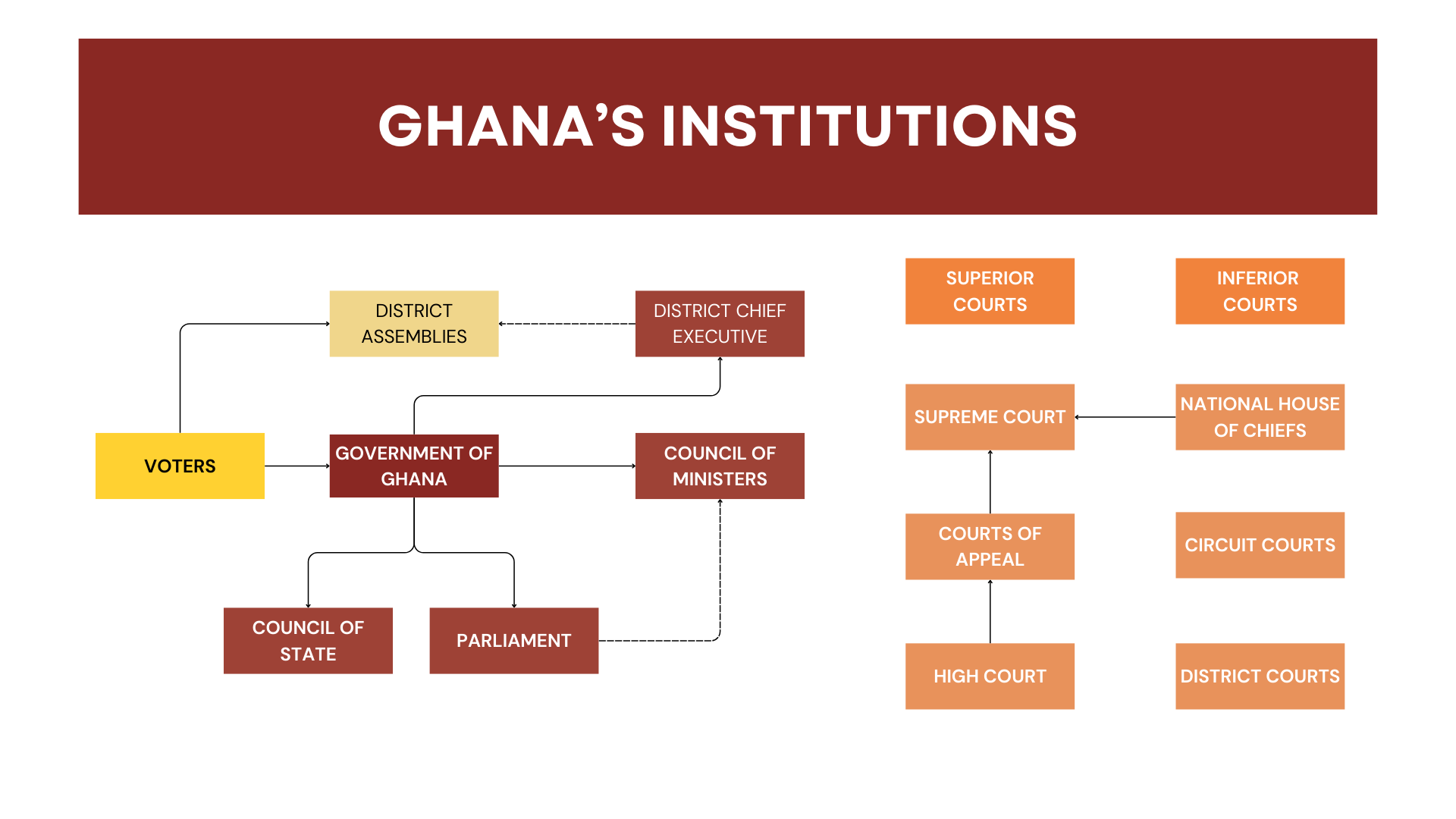

The Ghana Immigration Service is established under the Ministry of Interior with the responsibility to advise and ensure the effective implementation of all laws and regulations pertaining to immigration and related issues. The Immigration Service among other things is mandated to regulate and monitor the entry, residence, employment, and exit of all foreigners, and the movement of Ghanaians in and out of the country. Other migration-related institutions include the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Regional Integration charged with the control, direction, and coordination of Ghana’s external relations with an emphasis on regional integration as a foreign policy objective, and the Ministry of Employment and Labour Relations, which is tasked with the responsibility to coordinate and promote employment opportunities, decent jobs to all workers in Ghana, including migrant workers and Ghanaian working abroad.

Ghana's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

According to GSS (2014), 34.1% of the Ghanaian population were internal migrants in 2000, and 30.1% in 2010: the majority of people moved inter-regionally rather than intra-regionally, mostly towards urban areas. In 1970, 28.9% of the population lived in cities, whereas in 2000, 43.9% did. In total, migrants (5 years and over) contributed 4,656,959 people to the urban population in 2010, which was made up of 1,904,336 urban-to-urban migrants, and 2,752,623 rural-to-urban migrants – this means that 44.5% of the urban population (5 years or over) are migrants who arrived between 2000 and 2010 (GSS, 2014). Rural-to-urban migration and natural increase are considered the main contributors to this urbanisation. The main reasons behind this migratory route can be explained by economic, social and cultural forces – wage difference and welfare gap, social and cultural amenities in urban areas, parental control in rural areas, job availability, family reunification (GSS, 2014). In Ghana, this also means that internal migration is characterised by southward migration, as the north is mainly rural while the south is largely urbanised.

Among all internal migrant groups, females contribute more than males to the migrant population in the high migration age groups of 15-29 years old. Females are relatively more mobile that males in all regions except in Western and Brong Ahafo (GSS, 2014). Migrants are more likely to be managers and professionals than non-migrants, suggesting that it is the skilled and educated people who migrate.

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), conflict & disaster

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), conflict & disaster

Conflict and violence and disaster contribute to internal displacement in Ghana. However, disaster-related displacements are the main source of internal displacement in the country. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), (nd), between 2008 – 2022, there were 7,000 conflicts and violence-related displacements and 279,000 disaster-related displacements in Ghana.

Despite the relative peace that the country enjoys, inter-communal conflict remains the main source of conflict-related displacement in Ghana. For example, between 2018 and 2019, sporadic conflict over a piece of land with ancestral significance in the Northern region between the Chokosis and Kokombas communities displaced about 2,035 people (IDMC, 2020).

Increasing rural poverty, rapid urbanization, growth of informal settlements, poor urban governance, and declining ecosystem and land conditions shaped by demographic changes and development dynamics expose Ghanaians to the risk of disasters such as droughts, coastal erosion, floods, and landslides (World Bank, 2021). For example, flooding caused by high inflows of water to the Akosombo and Kpong dam reservoirs in the Volta region led to the displacement of 39,333 people across 9 districts (Displacement Tracking Matrix, 2023). The adverse effect of changing climatic conditions, does not only displace people but constitute a majour threat to livelihoods.

Immigration

Immigration

In the 1960s, Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Gambia were the migration hubs in West Africa and the preferred destination for most migrants from other parts of Africa as the countries offered a comparatively more favourable socio-economic and political situation (Adjepong, 2009). However, the enactment of the Aliens Compliance Order in 1969 that compelled all undocumented immigrants to leave the country within 14 days saw a mass expulsion of the immigrant population from the country.

The immigrant population as a percentage of the total population dropped from 12.3 in 1960 to 7% in 1970 (an estimated 155,000 and 213,000 immigrants were expelled) (Anarfi, nd). With the deteriorating economic situation of the country, the decline continued to 3.6% in 1984 and experienced a slight increase (3.9%) in 2000 (Ibid). According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), although the immigrant population has increased marginally from 337,800 (1.4% of the total population) in 2010 to 414,700 (1.5% of the total population) in 2015, and 476,400 (1.5% of the total population) in 2020, the immigrant population in both absolute and relative terms is far less than the pre-2000 figures. The top three origin countries of immigrants in Ghana are Togo (101,677), Nigeria (79,023), and Ivory Coast (72,728) (International Organisation for Migration, 2019).

Female/Gender Migration

Female/Gender Migration

According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), there has been a steady increase in the number of female international migrants in Ghana from 2010 when it stood at 157,700 to 193,700 in 2015, and recent figure indicates that there are 222,000 female migrants in Ghana as of 2020. Although there is a steady increase in the number of female migrants in Ghana, one needs to note that there are certain legal constraints that limit their opportunity to gain employment and create opportunities for themselves. Despite these limited opportunities, migrant women are involved in small-scale cross-border trade between Benin Ghana and Togo, mostly in the informal market (IOM, 2023).

Children

Children

According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), in 2010, of the 337,800 immigrants residing in the country, 31.1% (105,056) of them were children 18 years and younger. In 2015, of the 414,700 immigrants residing in the country, 22.4% (92,893) of them were children 18 years and younger (Ibid). In 2020, of the 476,400 immigrants in Ghana in mid-year 2020, 20% (95,280) of them were children 18 years old and younger (Ibid).

Although the figures represent a steady decrease in the number of child immigrants living in the country between 2010 and 2020, the numbers are still significant and require the government and the private sector to ensure that the needs of these young children, for example, access to health, education, and proper nutrition are attended to. According to Kyereko (2019), several factors contribute to limiting the access of migrant children to basic education which include a lack of awareness of free education at the basic level, differences in cultural and religious values between the migrant and the host community, inadequate financial resources, differences in gender norms and age of immigration, and temporary migration. However, a study conducted in the camps by Abdulla (2023), reveals that although the government propagates a free compulsory universal basic education for all children, including migrant children, not all children in the camps are provided with school uniforms, thus limiting their access to these institutions and some children in the camps are subjected to Child Sexual Abuse (CSA).

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Compared to other African countries like Uganda, South Africa, and Angola, Ghana has a low refugee and asylum seeker population. According to the UNHCR (2023), as of March and May 2023, there were a total of 11,028 refugees and asylum seekers in Ghana. The top 5 origin countries of refugees and asylum seekers in Ghana are Burkina Faso (3,220), Togo (3,473), Sudan (744), Ivory Coast (671), and Liberia (632).

The Ghanaian Refugee Board (GRB) under the Ministry of Interior in collaboration with the National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO), and the UNHCR are the main bodies that manage refugee-related issues including refugee status determination and the management of the refugee camps. Although Ghana does not practice an encampment policy for refugees, the country has 4 refugee camps namely the Ampain and Krisan refugee camps in the Western region, Egyeikrom refugee camp in the Central region, and Fetentaa refugee camp in the Brong-Ahafo region. However, urban refugees and asylum seekers live in metropolitan urban areas and surroundings, for example, in Accra. According to Masudi and Coffie, as cited by Abdullah et al. (2023), some of the challenges confronting refugees in Ghana include limited access to health care, food, and good sanitation and language barrier.

Emigration

Emigration

Before Ghana gained independence in 1957, the country experienced vibrant economic growth and an arguably stable political dispensation. However, after independence, there have been several political regimes alternating between military and civilian governments (up until 1992) and an economic downturn that made the country unattractive to migrants and encouraged emigration. According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), the number of emigrants leaving the country between 2010 and 2020 has experienced a steady increase from 762,000 in 2015 to 892,300 in 2015 and 1 million in 2020. According to the International Organisation for Migration (2020), the top ten destinations of emigrants from Ghana are Nigeria (233,002), United States of America (173,952), the United Kingdom (140,920), Ivory Coast (111,024), Italy (51,364), Togo (47,093), Burkina Faso (33,225), Germany (27,872), Canada (24,310), and Benin (16,056).

The above statistics indicate that historical emigration within the region (West Africa) is still a more common trend among Ghanaian migrants. Slow economic growth, and high unemployment levels amongst youths, as indicated above, have made the idea of emigration a popular discourse among Ghanaians, with 44% of Ghanaians, mostly young (56%) and unemployed (58%) expressing their intention to emigrate permanently (OECD, 2022). According to the World Bank (2024), in 2022, Ghana had a negative net migration (-9.999), indicating that more people were leaving the country than those coming into the country. The main driver of emigration in the country is unemployment and a mismatch between education and employment (OECD, 2022).

Labour Migration/Brain Drain

Labour Migration/Brain Drain

Considered the richest economy in West Africa because of its rich mineral deposits and vibrant cash crop agricultural activities, by the end of the first quarter of the 20th century and its Pan-Africanist political stance during its early years of independence, Ghana attracted migrant labour from all over the world and Africa in particular. Although historically, there was no data on the number of labour immigrants, most of them came from Mali, Burkina-Faso, Niger, and Togo and with the commencement of oil drilling in the country, more migrants were attracted to the country, mostly from Nigeria, Canada, the US, UK, Netherlands, and Germany (Anarfi, nd).

More recently, there are available data which indicate that in 2015, 70% of the international migration stock in Ghana were men and women of working age and the employment rate among them stood at 71.6% with more immigrant males (75.6%), being employed than females (68.7%) (IOM, 2020). While a small share of immigrants works in highly skilled roles within multinational companies, most immigrants work in the informal economy in sectors such as agriculture, retail and trade, manufacturing, and mining (Le Coz & Hooper, 2021). While immigrant men are concentrated mostly in agriculture and fishing, followed by wholesale and retail trade, immigrant women are mostly concentrated in wholesale and retail trade, followed by agriculture and fishing (Ibid). It is important to note that the different nationalities cluster in different occupations. For example, while Nigerians are concentrated in finance, insurance, mining, oil, and petty trading, Chinese nationals are concentrated in the gold mining sector (Ibid). It is also important to note that the concentration of migrant labour in the informal economy which in most instances is unregulated, increases the vulnerabilities of migrants to unfair labour practices, for example, exploitation.

Unauthorised Migration/Trafficking/Smuggling

Unauthorised Migration/Trafficking/Smuggling

Ghana is ranked Tier 2 in the Trafficking in Person (TIP) Report (2023) as the government of Ghana does not meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking although, in recent years, it has made some significant efforts, for example, increasing anti-trafficking law enforcement efforts. Ghana remains a source, transit, and destination for children and women subjected to forced labour and sex trafficking. Because of poverty and unemployment, traffickers, prey on the vulnerabilities of children and women who are in desperate search of opportunities. Traffickers exploit women and children both in Ghana and abroad. Abroad, some employment agencies exploit Ghanaian women and children, who travel particularly to the Gulf states as domestic workers. This precipitated the government to place a ban in 2017 on the issuance of visas for domestic workers from Ghana to work in the region (IOM, 2019b). In Ghana, traffickers exploit Ghanaian children through forced labour, inland and coastal fishing, domestic services, street hawkers, mining, and begging (US Department of State, 2023). Women who work as Kayayie (head portals) are sexually exploited through debt bondage and men are exploited through forced labour on the farms (Ibid).

The government in 2022, initiated the investigation of 133 trafficking cases, initiated the prosecution of 28 alleged traffickers (7 for sex trafficking, 14 for labour trafficking, and 7 for unspecified trafficking), and obtained a conviction for 10 traffickers (3 for sex trafficking, 5 for labour trafficking, and 2 trafficking for unspecified forms of trafficking) (US Department of State, 2023). During the reporting year (2022), the government referred 574 trafficking victims to services (government shelter services or NGOs) of which 217 were foreign nationals from Nigeria, Afghanistan, Benin, Burkina-Faso, Gabon, Mali, and Niger. The victims included 484 labour trafficking victims, 48 sex trafficking victims, and 6 unspecified trafficking victims, with the majority (361) of them being children (Ibid). An additional 249 trafficking victims, including 233 labour trafficking victims and 16 sex trafficking victims, were identified by NGOs (Ibid). The government expended 1,440,000 Ghanaians Cedis on services including medical care, needs assessments, psycho-social care, education and skills training, interpretation for foreign national victims, assistance obtaining identity documents, registration with national health services, and assistance during legal proceedings. The statistics above concerning the number of those who are victims of human trafficking reveals the hardship people are going through and their desire to break free.

Remittances

Remittances

In addition to reducing household poverty in Ghana, remittance flow contributes significantly to the growth of the Ghanaian economy. According to Abdulai (2022), the GDP growth rate in both the long and short term is positively impacted by an increasing flow of remittances into the economy of Ghana. According to The World Bank Group & KNOMAD (2023), in 2022, Ghana was ranked as the second top remittance recipient country after Nigeria in Sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Bank (2023), Ghana has experienced a steady increase in remittance flow into the country since 2018. In 2018, remittance flow stood at $3.52 billion (5.2% of GDP), in 2019, it increased to 4.05 billion (5.9% of GDP), in 2020, when there was a general economic downturn because of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, remittance flow into Ghana continued to increase to 4.29 billion (6.1% of GDP) (Ibid). However, it dropped slightly in 2021 to $4.17 billion (5.2% of GDP) and picked up in 2022 to $4.66 billion (6.3% of GDP) (Ibid). Drawing from the statistics above, an absence of remittances means a contraction in the economy and thousands of households being plunged into object poverty.

Returns and Returnees

Returns and Returnees

Push/Pull factors are relevant determinants of return migration in Ghana. While the socio-political and economic situation might not be so favourable for migrants in their host countries, migrants tend to look back at their home country with a cost/benefit perspective. The relative political and economic stability that Ghana has enjoyed in recent years has precipitated the return of many Ghanaians abroad. The government in collaboration with IOM has facilitated the voluntary return of thousands of Ghanaians (United Nations, 2023). Recently, in 2023, the IOM in collaboration with the Government of Ghana facilitated the return of 169 Ghanaians from Libya (136 men and 33 women) and assisted them in their reintegration process with the provision of economic, social, and psychosocial needs, which include education, or training to develop business and other skills (IOM, 2023). In addition to the services provided to returnees, the Ghanaian government in collaboration with ERRIN, established the Migration Information Centre for Returnees to assist returning migrants (International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD, 2022). Despite the efforts put in place by the government and international organisations to ease the reintegration process of returnees, they still encounter several challenges, including a lack of employment, family dependency, the mismatch between returnees' values and priorities and the socio-cultural convictions of non-migrants, and inadequate assistance from the government (Nartey, 2022). The differences between the government and members of the host communities on the one hand and the returnees on the other, if not adequately dealt with can escalate into tensions between the different parties.

Abdulai, A. 2022. The impact of remittances on economic growth in Ghana: An ARDL bound test approach. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23322039.2023.2243189#:~:text=The%20increasing%20flow%20of%20remittances,growth%20rate%20in%20both%20runs.

Abdullah, A. et al. 2023. Safeguarding the welfare of refugee children in Ghana: Perspective of practitioners in refugee camps. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S019074092200439X.

Achana, S. & Tanle, A. 2020. Experiences of female migrants in the informal sector businesses in the Cape Coast Metropolis: Is Target 8.8 of the SDG achievable in Ghana? African Human Review, Vol. 6(2):58-79. Retrieved from: https://sihma.org.za/journals/03%20Experiences%20of%20Female%20Migrants%20in%20the%20Informal%20Sector%20Businesses.pdf.

Adjepong, A. 2009. The origins, implementation and effects of Ghana’s 1969 Aliens Compliance Order. University of Cape Coast. Retrieved from: https://ir.ucc.edu.gh/xmlui/handle/123456789/1865.

Anarfi, J. nd. Immigration into Ghana since 1990. Regional Institute for Population Studies (RIPS), University of Ghana, Legon. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/countries/ghana/46733734.pdf.

Arthur-Holmes, F. & Busia, K. 2022. Women, North-South migration and artisanal and small-scale mining in Ghana: Motivations, drivers and socio-economic implications. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214790X22000375.

Bump, M. 2006. Ghana: Searching for opportunities at home and abroad. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/ghana-searching-opportunities-home-and-abroad.

CIA World Factbook. 2024. Ghana. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/ghana/.

Displacement Tracking Matrix. 2023. Ghana – rapid needs assessment of IDPs in Volta (October 2023). Retrieved from: https://dtm.iom.int/reports/ghana-rapid-needs-assessment-idps-volta-october-2023#:~:text=The%20Volta%20Region%20in%20Ghana,essential%20services%20has%20been%20disrupted.

Ghana Statistical Service. 2014. 2010 Population & Housing Census Report. Retrieved from: https://www.statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/Migration%20in%20Ghana.pdf.

Ghana Statistical Service. 2019. Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS) 7: Main Report. Retrieved from: https://www.statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/GLSS7%20MAIN%20REPORT_FINAL.pdf.

ICMPD. 2022. Opening of migration information centre for returnees in Ghana in the framework of the ERRIN project. Retrieved from: https://www.icmpd.org/news/opening-of-migration-information-centre-for-returnees-in-ghana-in-the-framework-of-the-errin-project.

IDMC. 2020. Ghana: Displacement associated with conflict and violence. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/GRID%202020%20%E2%80%93%20Conflict%20Figure%20Analysis%20%E2%80%93%20GHANA.pdf.

IDMC. 2024. Country profile: Ghana. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/ghana/.

IOM. 2018. Migration governance snapshot: the Republic of Ghana. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/sites/g/files/tmzbdl251/files/2018-05/MGI%20report%20Ghana_0.pdf.

IOM. 2020. Migration in Ghana: A country profile 2019. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mp-_ghana-2019.pdf.

IOM. 2019b. Ghanaian domestic workers in the Middle East. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/country/docs/ghana/iom_ghana_domestic_workers_report_summary-finr.pdf.

IOM. 2023. Collaboration with government partners ensures safe voluntary return of 169 Ghanaian migrants. https://rodakar.iom.int/news/collaboration-government-partners-ensures-safe-voluntary-return-169-ghanaian-migrants.

IOM. 2023. IOM and government partners in Benin, Ghana, and Togo work together to empower women in small-scale cross-border trade. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/news/iom-and-government-partners-benin-ghana-and-togo-work-together-empower-women-small-scale-cross-border-trade.

IMF. 2024. Ghana: Transforming a crisis into a journey toward prosperity. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2024/01/29/cf-ghana-transforming-a-crisis-into-a-journey-toward-prosperity.

Kyereko, O. 2019. Education for All: the case of out-of-school migrants in Ghana. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-21092-2_2.

Lattof, R., et al. 2018. Contemporary female migration in Ghana: Analyses of the 2000 and 2010 census. Retrieved from: https://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol39/44/39-44.pdf.

Le Coz, C. & Hooper, K. 2021. Deepening labour migration governance at a time of immobility. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/mpi-labor-migration-governance-ghana-senegal-2021_final.pdf.

Migration Data Portal. 2021. Ghana. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/.

Nartey, A. 2022. Socio-economic realities of returned immigrant reintegration in Ghana: A systematic review. E-Journal of Humanities, Arts and Social Science, Vol.3(12):613-635. Retrieved from: https://noyam.org/?sdm_process_download=1&download_id=8383.

OECD. 2022. A review of Ghanaian emigrants. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/d716599e-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/d716599e-en.

Sertich, M. & Heemskerk, M. 2. 011. Ghana’s Human Trafficking Act: Successes and shortcomings in six years of implementation. Human Rights Brief, Vol. (1):2-7. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief/vol19/iss1/1/.

The World Bank Group & KNOMAD. 2023. Remittances remain resilient but are slowing: Migration and Development Brief 38. Retrieved from: https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/publication-doc/migration_development_brief_38_june_2023_0.pdf.

Turolla, M. & Hoffmann, L. 2023. “The Cake is in Accra”: a case study on internal migration in Ghana. Retrieved from: https://www.ug.edu.gh/mias-africa/sites/mias-africa/files/images/MIASA%20WP_2022%282%29%20Turolla%26Hoffmann_.pdf.

UNHCR. 2019. Ghana’s progressive asylum system hailed as the country joins the rest of the world to mark World Refugee Day. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/gh/2019/06/20/ghanas-progressive-asylum-system-hailed-as-the-country-joins-the-rest-of-the-world-to-mark-world-refugee-day/#:~:text=a%20country%20site%3A-,Ghana's%20progressive%20asylum%20system%20hailed%20as%20the%20country%20joins%20the,to%20mark%20World%20Refugee%20Day&text=Deputy%20Minister%20for%20the%20Interior,are%20eliminated%20in%20the%20society.

UNHCR. 2023. Fact Sheet: Ghana. Retrieved from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/ghana-factsheet.

United Nations. 2023a. Youth unemployment is the most common driver of vulnerability to violent extremism and radicalisation in Northern regions of Ghana – New UNDP Ghana report. Retrieved from: https://ghana.un.org/en/238758-youth-unemployment-most-common-driver-vulnerability-violent-extremism-and-radicalisation.

United Nations. 2023b. IOM welcomes home 162 Ghanaian migrants from Libya. Retrieved from: https://ghana.un.org/en/244685-iom-welcomes-home-162-ghanaian-migrants-libya.

US Department of State. 2023. Trafficking in person report: Ghana. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/ghana/#:~:text=Traffickers%20exploit%20Ghanaian%20children%20in,especially%20in%20the%20cocoa%20sector..

World Bank. 2021. Climate change knowledge portal for development practitioners and policy makers: Ghana. Retrieved from: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/ghana/vulnerability#:~:text=Historical%20Hazards,declining%20ecosystem%20and%20land%20conditions.

World Bank. 2023. Personal remittances, received (current US$) – Ghana. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT?locations=GH.