Historical Background

Historical Background

Ethiopia is the continent’s oldest independent country and the second most populous, with over 100 million people. Except for a brief period under Italy’s Mussolini, the country has always maintained its independence. Ethiopia is a landlocked country largely dependent on its neighbour Djibouti for port access. It is a majority Christian country and is home to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. While Ethiopia has one of the lowest inequality ratios in the world, it also has one of the highest rates of poverty. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who came to power in 2018, has made impressive strides in fostering a more open and freer political and media environment, and he recently won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work ending the conflict with Eritrea. Currently, Ethiopia’s greatest challenges are continuing to lift the population out of poverty through sustained economic growth, creating political stability, and increasing competition in the size of the private sector (BBC, 2019).

Ethiopia is landlocked and shares borders with all the countries of the Horn of Africa. This positions the country as a hub and transit route for migration, besides being a point of departure and destination for migration.

Although migration abroad used to be uncommon in Ethiopia, Ethiopians started moving abroad in the 20th century to study at Western universities and to complete higher education. The military coup of 1974 ending imperial rule triggered internal displacement and migration to neighbouring countries. Many Western countries offered resettlement to the Ethiopians in camps (Terrazas, 2007). The national capital, Addis Ababa, has also been a popular destination for internal migrants fleeing ethnic violence, and the city has grown from a population of 1.4 million in 1984 to an estimated population of more than 3.5 million in 2000 (Terrazas, 2007).

In 2018, it was estimated that Ethiopia and Uganda hosted 1.2 and 1.8 million refugees, respectively, the largest number of African migrants in the East Africa region (encompassing 18 countries) (UNHCR, 2019). Major migration push factors include poverty, conflict, environmental crises such as droughts and floods, conflict in South Sudan, economic deprivation and open-ended military service in Eritrea, and conflict and conflict-induced food insecurity in Somalia (Abebe, 2018a). Ethiopia’s 2018 peace agreement with Eritrea was preceded by a spike in migration from Eritrea into Ethiopia (European Commission, 2019).

Although Ethiopia has one of the fastest-growing economies, it is also one of the poorest, with a per capita income of $790 (World Bank, 2019). From 2007/08 to 2017/18, Ethiopia’s economy experienced strong growth, averaging 9.9% a year compared to a regional average of 5.4%. The country aims to reach middle-income status by the end of 2025 (World Bank Group, 2019). Migration into Ethiopia is impacted by the attraction of the country’s fast and steady economic growth on the one hand and spikes in intercommunal violence, political protests, and environmental disasters on the other (Migration Data Portal, 2019).

Migration Policies

Migration Policies

Ethiopia was one of the first countries to implement the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF) developed out of the Summit on Refugees and Migrants hosted by the United Nations General Assembly in September 2016. The summit outlined the main points of the CRRF, aimed at supporting both refugee and host community populations. Here, Ethiopia committed to nine pledges pertaining to providing work permits to qualifying refugees, facilitating local integration, and reserving a small percentage of jobs within the industrial sector for refugees. These commitments were followed through in its 2019 amended Refugee Proclamation. National consultations with a diverse range of actors are ongoing to plan and facilitate the implementation of Ethiopia’s nine pledges (UNHCR, 2018). The country is now widely considered a leading example with its comprehensive and robust refugee protection policies (Abebe, 2018a). Implementation to date includes the initiation in October 2017 of the civil registration of refugees, including birth, marriage, divorce, and death for new refugees, as well as retroactive registration access for approximately 70,000 refugee children born in the country in the past 10 years. Additionally, a countrywide refugee registration infrastructure was launched in 2017 to consolidate information on the refugees’ education, professional skills, and family profiles. This biometric information management system will enable refugees to access CRRF opportunities, such as jobs created through Ethiopia’s $500 million new industrial parks funded by the European Union (EU), bearing in mind that 30% of these jobs are open to refugees (ISS, 2018).

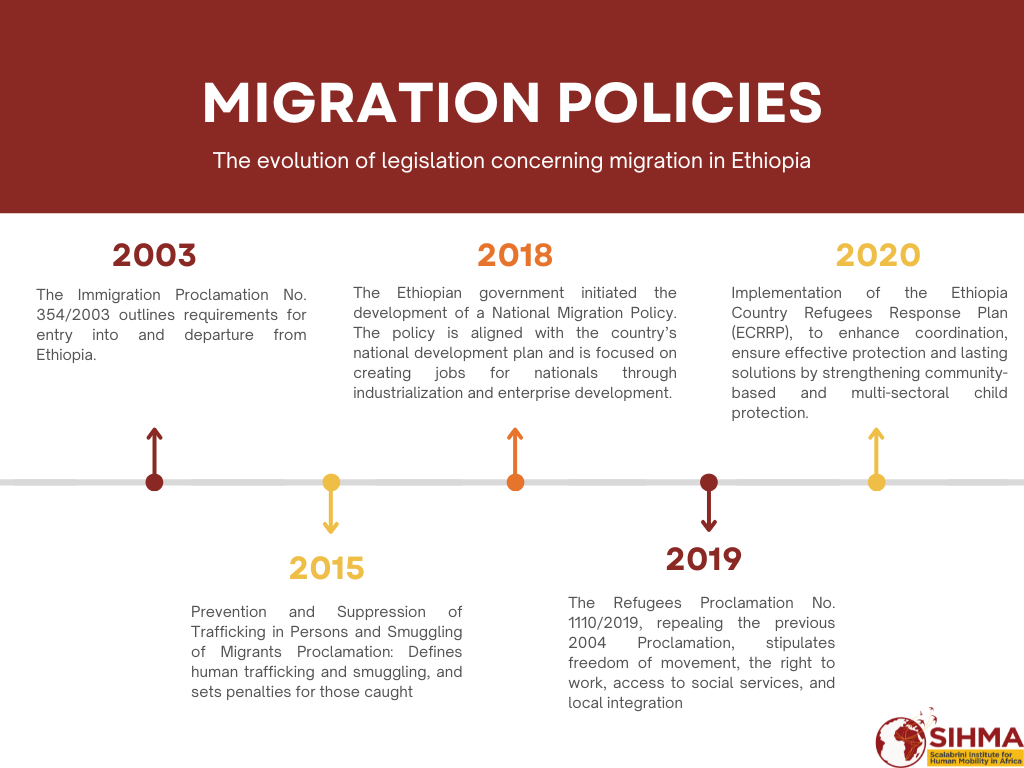

Ethiopia has various policies and proclamations directly addressing migrants and refugees. The Immigration Proclamation No. 354/2003 of 2003 outlines requirements for entry into and departure from Ethiopia, including travel documents, visas, registration, and residence permits (National Legislative Bodies, 2003). The Security, Immigration and Refugee Affairs Authority Establishment Proclamation No 6/1995 establishes an authority to “execute policies and laws on the state and public security, immigration nationality and refugees” (National Legislative Bodies, 1995).

Timeline of Migration Policies in Ethiopia. Source: SIHMA

In 2019, Ethiopia passed Refugees Proclamation No. 1110 of 2019, which repeals Refugee Proclamation No. 409 of 2004 and provides a more comprehensive outline of protection and assistance to refugees in the country (National Legislative Bodies, 2019). It stipulates freedom of movement, the right to work, access to social services, and local integration. The new law allows refugees to obtain work permits, access primary education, obtain driver’s licenses, legally register life events such as births and marriages, and opens up access to national financial services such as banking (UNHCR, 2019b). The UNHCR calls it “one of the most progressive refugee policies in Africa”. Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, said that “the passage of this historic law represents a significant milestone in Ethiopia’s long history of welcoming and hosting refugees from across the region for decades”, adding the following: “By allowing refugees the opportunity to be better integrated into society, Ethiopia is not only upholding its international refugee law obligations but is serving as a model for other refugee hosting nations around the world” (UNHCR, 2019a).

Ethiopia’s refugee policy requires refugees to live in camps, except for a small number of people who are allowed to stay in urban centres due to special considerations. Since 2010, many more have been given the option of living outside of the refugee camps as part of the government’s Out of Camp Policy (Abebe, 2018a).

Ethiopia is a signatory to the:

-

OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa

-

UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, 1951 (ratified 1969)

-

UN Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1967 (ratified 1969)

-

UN Human Trafficking Protocol, 2000 (ratified 2012)

-

UN Migrant Smuggling Protocol, 2000 (ratified 2012).

In 2018, Ethiopia lifted a five-year ban on Ethiopian migrants seeking work abroad in the Gulf region (Walk Free Foundation, 2019). Instituted to protect migrants against exploitation, it put Ethiopian migrants at greater risk of trafficking and exploitation since economic desperation pushed people to ignore the ban and travel overseas regardless (AFP, 2018). The new legislation establishes regulations for recruitment agencies, including minimum age, education requirements, and training for migrant workers before departure (Walk Free Foundation, 2019).

Additional related policies are the Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, the Proclamation to Regulate the Issuance of Travel Documents and Visas, and Registration of Foreigners in Ethiopia (1969), the Issuance of Travel Documents and Visas regulations (1971), the Security, Immigration and Refugee Affairs Authority Establishment Proclamation (1995), the Prevention and Suppression of Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants Proclamation (2015) and the Overseas Proclamation (2016).

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

The primary body responsible for handling migration issues is the Department for Immigration and Nationality Affairs. The Administration for Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA) “hosts asylum-seekers seeking a safe haven in Ethiopia as a result of man-made or natural disasters. The agency creates platforms that enable and assist refugees in escaping poverty by finding durable solutions and strengthening people-to-people relations” (ARRA, 2020). The agency is also responsible for receiving Ethiopian refugees. The Security, Immigration and Refugee Affairs Authority (SIRAA) is responsible for enforcing public security, immigration, nationality, and refugees. The lead coordinator for referring trafficking victims to services (legal, psychosocial, medical, etc.) is the National Anti-Trafficking Council and Task Force in coordination with various government agencies.

Ethiopia's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

The Diaspora Engagement Affairs General Directorate is charged with coordinating diaspora issues at the national and regional levels. The Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia is designated to provide all surveys and censuses used to monitor economic and social growth, including data collection and reports on refugees in the country.

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

In the Horn of Africa and in Ethiopia, government attention to facilitating safe internal migration, predominantly rural to urban, is crucial to build inclusive and resilient cities. Factors driving internal migration include climate change, job and education opportunities, and the evolving desires of young people (REF, 2016). Additional push factors include overpopulation, famine, poverty, land scarcity, governmental agricultural policies, and lack of agricultural resources (Ezra & Kiros, 2001). The two most important factors, however, are age and education. The majority of migrants are young and are better educated than non-migrants (Bundervoet, 2017). Research published in 2017 based on a study in Southern Ethiopia revealed that 76.2% of migrants left home between the ages of 16 and 25, while 48% of migrants were attending junior education level at the time of departure, and 80% were unmarried. The primary reasons for rural-urban migration were better job opportunities (44%), rural poverty (26%), further education opportunities (10%), starting a business (8%), freedom from cultural restrictions (8%), and better urban services (4%) (Eshetu & Mohammed, 2017).

A study on migration in southern Ethiopia revealed that female migrants tend to move shorter distances while men are more likely to venture farther from their place of birth. The mean distance travelled by men in the study was 80.50 kilometres; for women, it was 63.08 kilometres (Eshetu & Mohammed, 2017).

Research on internal migration remains limited, with the most recent comprehensive numbers dating from the 2013 Labour Force Survey (LFS). In the five years before the 2013 LFS, about 6.5% of the Ethiopian adult population had migrated, marginally higher than the share in 1999 (5.7%). Rural migration remained low in 2013, with only 3.5% of the total adult population moving zones between 2008 and 2013. Of the total migrant population, the majority were moving from rural to urban settings. From 2008 and 2013, 34% of migrant pathways were rural to urban while 25% were intra-urban and 23% were intra-rural. These numbers are reflected in the proportion of migrants in urban areas: in 2013, 17% of urban dwellers were recent migrants (within the previous five years) while 55.4% were all-time migrants. While migrants comprise a greater proportion of the total population in smaller cities, the largest volume of rural-urban migrants headed for Addis Ababa (39% of all rural-urban migrants) (Bundervoet, 2017). On a general scale, Endris and Kassegn (2021) estimated that 50% to 70% of the population moves briefly within the country. Development projects are concentrated in urban areas, which attracts migrants from the rural to the urban areas. The relative availability of opportunities in urban areas therefore attracts migrants searching for livelihoods.

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), conflict and Disasters

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), conflict and Disasters

In 2022, a total of 3.9 million people were displaced because of conflict/violence in Ethiopia while another 873,000 were displaced because of disasters (IDMC, 2023).

Ethiopia has a complex history of internal conflict as well as ongoing conflict with neighbouring Eritrea perpetuated by ethnic divides and consequentially operated along ethnic lines. The features of Ethiopia’s government structure and the ethnic separation of administrative districts in the country have led to a natural formation of self-governing entities made up of specific ethnic groups such as the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Amhara Democratic Party (ADP). These ethnic groups struggle to find neutrality on land issues and themes of ethnic superiority which often amount to human rights violations that have forced people out of their respective regions.

A defining period in Ethiopia’s history is 1974 to 1991 when the country endured a civil war largely driven by ethnic differences and the disdain of rebel forces for the sitting government’s rule. Before the government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front signed the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement (CoHA) in November 2022, Ethiopia was in the midst of a raging civil war that officially launched as a result of an offensive enacted by the ruling party under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in November 2020. Perpetuated also by conflicts with Eritrean forces in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, the country is facing a severe crisis without a clear end in sight. Again, along ethnic lines, the sitting Ethiopian government, largely made up of members of the now-dissolved ADP and members of the TPLF, started to engage in acts of militarism after TPLF leaders held a regional election in opposition to the prime ministerial election of the newly formed Prosperity Party leader, Abiy Ahmed (Gebre, 2020).

Although the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement reduced the number of conflict-related displacements from 3.9 million in 2022 to 2.9 million by the end of 2023, enabled better humanitarian access, and allowed the return of thousands of people in 2023, the situation is still volatile as the region still accounts for the highest number of internally displaced people (949,000) (IDMC, 2025). Also, the situation is compounded by renewed fighting in Amhara and Oromia causing the displacement of 407,000 and 140,000 people in the respective regions (ibid). The unstable political situation in some of the regions is an indication that the country will continue to experience conflict/violence-related internal displacements.

Also, Ethiopia is disadvantaged by natural disasters driven largely by climate change including drought, flood, earthquakes, and pest problems. These disasters vary in frequency and severity (Tesso, 2019). Drought and flooding have proven to be the most problematic natural hazards that have impacted the largest portion of Ethiopia’s population. The impact of drought in the country can be seen in the 2011 Horn of Africa drought that left 4.5 million people in a state of food insecurity. In January 2023, 781,344 people were internally displaced because of droughts in Ethiopia (IOM, 2023).

The agriculture sector accommodates an estimated 75% of Ethiopia’s workforce, which gives additional context to how detrimental climate-impacting disasters and conflict/violence can be in the country and how such events can contribute to internal displacement beyond destructive causes.

Immigration

Immigration

Although internal conflict and natural disasters adversely affect Ethiopia, its rich history and location in the Horn of Africa position it as a transit country and an attractive destination for immigrants in the region. According to UN DESA (2021), in 2010, the immigrant population stock stood at 568,700 and it almost doubled to 1,000,200 in 2015 and dropped slightly to 1,000,100 in 2020. The majority of migrants in Ethiopia come from Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea. However, other migrants come from Rwanda, Burundi, Angola, Liberia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Uganda, South Africa, and Yemen. Although there is a paucity of information on the demographics of the immigrant population in Ethiopia, Zekarias (2023) posited that the strong ethnic and cultural bonds between communities living at the borders – such as Ethio-Kenya, Ethio-Somalia, and Ethio-Sudan – enforce cross-border activities including informal trading. For many living within these cross-border regions, borders are a mere distraction to their common livelihood challenges.

Gender/Female Migration

Gender/Female Migration

There is a scarcity of information on the conditions of female international migrants in Ethiopia. According to UN DESA (2019), as a percentage of the international migration stock, the stock of female international migrants between 1990 and 2010 was fairly stable, fluctuating between 47.4% and 47.6%. However, the country experienced an increase from 2015 to 2020. As a percentage of female international migration stock, it stood at 49.1% in 2015 and 50.5% in 2020 (UN DESA, 2021). There is limited information on the demographics of female immigrants in Ethiopia. However, there is a plausible amount of literature on female emigration as explained in the section on emigration.

Children

Children

Despite the prevalence of child migration in Ethiopia, there is no comprehensive data on the nature of child migration in the country. Different reports highlight specific information on child migration in the country. For example, according to a UNHCR 2001 – 2022 report, Ethiopia hosts the largest number (41,000) of unaccompanied and separated children in the world, with most of them fleeing conflict in South Sudan. The report also indicates that 60% of the over 337,000 refugees in the seven camps of Gambella are children (ibid). Within Ethiopia a total of 7,883 minors have returned through a joint EU and IOM initiative (IOM, 2022). This represents the mix-migration flow in the country. While child migrants are entering Ethiopia from other countries as indicated below, Ethiopian minors are also returning from other countries.

In a 2018 study by the Mixed Migration Centre’s Mixed Migration Monitoring Mechanism Initiative with UNICEF, over 870 children (455 girls and 415 boys) between the ages of 13 and 17 were interviewed to understand the rationale of their migration. The children came from a variety of countries, including Angola, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. About half of the children who participated in the study noted their primary reason for leaving home was violence and general insecurity, followed by personal/family reasons, financial reasons, a lack of freedom and/or discrimination in their country of origin, and a lack of social services. The children reported that they chose destinations where they thought they would have better chances of getting a job and sending remittances home, and where there would be improved general security, and opportunities to access better education, reunite with family, and access better medical care (IOM, 2019a). Most of the child migrants, especially if returning from abroad or having survived exploitation, often require shelter, psychosocial support, family tracing and reunification, and reintegration into their communities of origin (IOM, 2019b). Ethiopia’s position in the Horn of Africa and its relative stability in the region make it a destination for most migrant children fleeing from war-torn countries within the region. The anecdotal nature of statistics on child migrants in the country poses a complex challenge as most of them who require assistance will not be easily identified and supported.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Ethiopia is the third largest refugee-hosting country on the continent, with 1,073,275 refugees and asylum seekers by December 2024 (UNHCR, 2024). South Sudan refugees constitute the highest refugee population (429,216) hosted in Ethiopia, followed by Somali refugees (361,949) and Eritrean refugees (179,118) (ibid). Refugees and asylum seekers also come from other continents including Asia. Most of the refugees are housed in 26 refugee camps across the country, though the government since 2010 has been exploring an Out of Camp Policy that would allow refugees to live in other locations (Abebe, 2018a).

The three locations that host the highest number of refugees and asylum seekers are Gambela (395,590), Somali (360,715), and Benishangul-Gumuz (105,079) (UNHCR, 2023). Children under 18 account for 48% of refugees in the camps in the northern part of Ethiopia (Abebe, 2018b). At the end of 2017, 87,400 Ethiopian refugees (0.1% of the population) were heading primarily for Kenya (17,873), South Africa (17,562), the United States (9,987), Yemen (6,205), and South Sudan (4,555) (European Commission, 2019). Following the resurgence of the Tigray conflict in northern Ethiopia, the number of Ethiopian refugees has surged recently. For example, in 2022, Sudan hosted more than 73,000 Ethiopian refugees (UNHCR, 2022). The recurrent conflict in the Horn of Africa positions Ethiopia not only as a destination country for refugees and asylum seekers but also as an origin country.

Emigration

Emigration

Migration out of Ethiopia was minimal until the revolution of 1974 which installed the Derg, a Marxist military regime. Previously, only small numbers of the political elite left the country to study in the West and returned home to guaranteed positions of power and privilege. After 1974, a refugee crisis emerged as outflows due to political persecution and economic desperation spiked, only falling after the end of the Derg in 1991 and finally reaching a net migration rate of zero by 2007 (Terrazas, 2007). In 2017, the net migration rate in Ethiopia was estimated as -0.2 migrant(s)/1,000 population (MPI, nd). Towards the end of 2017, there were 800,900 (0.8% of the population) Ethiopian migrants outside the country. Migrants predominantly travel to the United States (217,913), Saudi Arabia (148,753), Israel (78,489), Sudan (71,631), and Kenya (36,692) (European Commission, 2019).

The majority of Ethiopian migrants emigrating out of the country are women (86%) looking for employment opportunities, primarily as domestic workers in the Middle East. 100% of Ethiopian migrant workers in Oman report working as housemaids, while in Lebanon it stood at 81.8% and in Kuwait at 75.5% (IOM, 2017). From 2008 to 2013, it was reported that 297,512 female domestic workers from Ethiopia’s three key regions of origin – Amhara, Addis Ababa, and Oromia – were legally working in the Middle East. This number may be double. In 2013, the government banned migration to Saudi Arabia to protect against labour exploitation. The ban was lifted in 2018 (Walk Free Foundation, 2019). However, due to the volume of migrants using irregular channels to evade the government’s ban on labour migration to the Middle East at that time, the actual figures remain unknown. The ban was enacted to curb labour exploitation after Saudi Arabia expelled over 160,000 Ethiopians from Saudi Arabia between 2013 and 2014, and over 84,000 Ethiopian migrant workers were either voluntarily repatriated or forcibly deported in 2017 (Ayalew et al., 2019). Around the time of the ban, an estimated 1,000 Ethiopian women were leaving the country daily in search of employment abroad, predominantly in Saudi Arabia. Reports of exploitation from employers include passport confiscation and underpayment, as well as physical, sexual, and emotional exploitation (Walk Free Foundation, 2019).

There are four key migration routes from Ethiopia: the Eastern Route, the Northern or Central Mediterranean Route, the Sinai Route, and the Southern Route. The Eastern Route runs from the East and Horn of Africa through Yemen to the Gulf Countries, especially Saudi Arabia. The Northern Route (also known as the Central Mediterranean Route) takes migrants from the East and Horn of Africa to Europe across the Mediterranean Sea, mainly departing from Libya and heading for Italy. The Southern Route (through Kenya towards South Africa) connects the East and Horn of Africa to South Africa. The Sinai Route, the least common now, runs from the East and Horn of Africa through Sudan and Egypt into Israel. The Eastern and Southern routes are the most common (Marchand et al., 2017). From January to December 2018, data from IOM reveals that 59.93% of Ethiopian migrants were moving within the Horn of Africa, 20.37% headed for the Eastern Route, 14.21% for the Northern Route, 4.94% for the Southern Route, and 0.55% for the other routes. The primary challenges that migrants reported on these routes were “hunger and thirst”, followed by “sickness” and “financial issues” (DTM, 2018). When legal pathways of migration become increasingly limited, migrants resort to irregular migration routes, creating an illicit economy for traffickers and smugglers.

Labour Migration/Brain Drain

Statistics on inward labour migration flow to Ethiopia are sketchy and anecdotal. However, there are numerous studies on the outward labour migration flow from Ethiopia. The labour migration pattern from Ethiopia comprises both skilled and unskilled migrants. Referring to skilled migrants, Ethiopia suffers greatly from both “brain drain” and “brain hemorrhage” as opportunities for highly skilled and educated Ethiopians are limited at home. International migrants with tertiary education accounted for 6,400 in 2017 (UNESCO, 2017). For example, despite the government’s restrictive measures (control of passports, compulsory community service for graduates) to limit the outward migration of trained medical personnel, in 2008/2009 the country lost 29% of its medical personnel to emigration (Degu, 2021). Despite the unconstitutionality of these restrictive measures that seek to limit the free movement of people, it proved to be a futile exercise. High rates of poverty and low levels of education make it difficult for the country to build and retain a sizeable skilled workforce or even to create sufficiently attractive opportunities to entice professionals in the diaspora to return (Fransen & Kuschminder, 2009).

In addition to the labour migration of skilled Ethiopians, there is also the labour migration of unskilled Ethiopians at a higher rate, who in most cases, are irregular migrants. Saudi Arabia remains the primary destination for irregular migrants, representing 80% to 90% of Ethiopian labour migration. Reportedly, according to international aid agencies as cited by the International Bar Association (2023), 750,000 Ethiopians reside in Saudi Arabia, with half of them undocumented. Although trapped in a war-torn zone, tens of thousands of Ethiopians make the perilous journey to Yemen every year in search of better work opportunities (VOA, 2023). However, with the ongoing civil war in Yemen, migrant labourers are stuck in Yemen with no work (ibid). Unemployment, poverty, inadequate infrastructural development, and poor working conditions, which were some of the push factors of labour migration from Ethiopia over the past decade, are still very much the same drivers in 2025. This entails a similar pattern of labour migration in the country.

Unauthorised Migration/Trafficking, Smuggling

Unauthorised Migration/Trafficking, Smuggling

According to the US Department of State (2024), Ethiopia is a Tier 2 country as the government is making significant efforts in some respects but does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking. Traffickers typically operate in two contexts: i) targeting parents of children in rural areas to provide them with housing and education in urban centres in exchange for domestic work, and ii) targeting migrants headed for the Gulf States for labour, often domestic work. In both situations, victims are vulnerable to labour, sexual, and other forms of exploitation. Girls from Ethiopia’s impoverished rural areas are exploited in domestic servitude and commercial sex within the country, while boys are subjected to forced labour in traditional weaving, construction, agriculture, and street vending (US Department of State, 2024).

Many Ethiopian women working in domestic service in the Middle East face severe abuses, including physical and sexual assault, denial of salary, sleep deprivation, passport confiscation, and confinement. Ethiopian women who migrate for work or flee abusive employers in the Middle East are also vulnerable to sex trafficking. Ethiopian men and boys migrate to the Gulf States and other African nations, where traffickers subject them to forced labour. Local NGOs assess that the number of internal trafficking victims exceeds that of external trafficking, particularly children exploited in commercial sex and domestic servitude. Most traffickers are small local operators, often from the victims’ communities, although crime syndicates are also responsible (United States Department of State, 2019). The huge number of IDPs and refugees in the country do not have access to justice, education, and financial opportunities, which increases the vulnerability of displaced people as victims of human trafficking (US Department of State, 2023).

In 2023, the government identified 541 Ethiopian victims of human trafficking (278 in sex trafficking, 263 in labour trafficking) while international NGOs reported identifying 4,200 potential trafficking victims (ibid). Victims were assisted with medical care, shelter, legal aid, psychosocial counselling, education, reintegration assistance, repatriation assistance, and financial assistance (ibid). Although the identified victims were far fewer than the potentially identified victims, the high number of potentially identified victims signals the enormity of the problem of human trafficking in the country. In 2023, the government reported investigating 728 trafficking cases (21 labour trafficking, 707 for unspecified forms of trafficking), prosecuting at least 650 individuals in 531 cases (2 for sex trafficking, 15 for labour trafficking, and 633 for unspecified forms of trafficking), and obtained convictions for 243 traffickers (41 for labour trafficking and 202 for unspecified forms of trafficking) (ibid).

The difficult migration routes from the Horn of Africa make many migrants turn to smugglers to facilitate the journey. Although geography favours migratory routes, the routes are physically dangerous. Introductions are often made through local brokers, returnees, relatives, and/or friends. Working with a smuggler makes migrants vulnerable to exploitation, as brokers and agents can make false promises and give limited information on labour opportunities or, in worst cases, exploit or traffic migrants. According to an ILO study (2017) on 1,450 potential migrants, more than 30% of the respondents stated that they received no information on the nature of the jobs, while 54% had not received any information on their employers (ILO, 2017). As migration increasingly becomes a survival mechanism for most migrants, the challenges of using the legal pathways of migration, including administrative challenges in obtaining a visa, mean that migrants will resort to using irregular pathways, making them potential victims of human trafficking.

Remittances

Inadequate opportunities, poverty, and political factors have turned migration and remittances into a source of livelihood for many households in Ethiopia. From 2014 to 2017, remittances comprised 1% to 1.1% of the country’s GDP, with the total value increasing proportionally alongside the GDP from €470 million in 2014 to €721.9 million in 2017 (Ursa et al., 2019). Personal remittances received in Ethiopia was at its all-time high in 2014, when it stood at $1.8 billion. It experienced a steady decline from 2015 ($1.09 billion) to 2017 ($393,379,170) and started increasing in 2018 ($436,325,463) and 2019 ($479,624,165). It declined again in 2020 ($404,088,320) and increased steadily in 2021 ($447,647,084), 2022 ($510,201,215), and 2023 ($539,360,389). Because Ethiopia lacks a robust banking infrastructure and formal remittance service providers, informal remittances are estimated to be extremely high (Marchand et al., 2017). According to Cenfri (2018), the informal flow of remittances is estimated to be as high as 78% of total remittances in the country.

According to Ratha and Mohopatra as cited by Zerihun (2020), Ethiopia is one of the largest remittance-receiving countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Remittance constitutes a vital source of foreign exchange as it is estimated to be larger than foreign earnings (ibid). When remittances go beyond contributing to household consumption to contributing to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the country, the remittance flow helps to drive the country’s economic growth trajectory and therefore needs to be encouraged and promoted.

Returns and Returnees

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2019c), Ethiopian returnees from Africa’s Eastern migratory route are coming back to their country at a rate of about 1,000 migrants per month. From January to October 2019, IOM Ethiopia assisted 9,200 returnees (ibid). This represents close to a twofold increase compared to 2018 when 5,382 returnees were assisted by IOM (ibid). According to IOM (2019c), between May 2017 and July 2019, some 21,657 Ethiopian minors returned to Ethiopia from Saudi Arabia, comprising 8% of the total number of returnees from Saudi Arabia to the Horn of Africa. In May and June 2019, IOM aided the repatriation of almost 3,000 Ethiopian migrants detained in Yemen, including 1,236 unaccompanied children (IOM, 2019b).

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic precipitated the return of an estimated 550,000 Ethiopian migrants from the Gulf countries in 2020 (UN Women, 2021). After cracking down on illegal labour migration and expelling Ethiopians from the country, Saudi Arabia offered an amnesty period from March to November 2017 to allow irregular migrants to voluntarily leave the country. During this period, a reported 100,000 migrants returned to Ethiopia (United States Department of State, 2019). Faced with the challenge of reintegrating within their communities, the International Labour Organization (ILO), through its FAIRWAY programme in collaboration with the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, provides financial assistance to returnees to facilitate their integration process (ILO, 2021). Also, through the Good Samaritan Association (GSA), safe accommodation, medical care, psychological counselling, and vocational training are provided to returnees (UN Women, 2021). Recently, the relatively high numbers of Ethiopian returnees can be attributed to factors such as the securitisation of migration in Saudi Arabia, the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the political instability in Yemen.

International and Civil Society Organizations

International and Civil Society Organizations

Various UN agencies in Ethiopia work to solve some of the most prevalent issues in the country. Here, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), International Labour Organization (ILO), International Organization for Migration (IOM), and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) are examples of United Nations entities that seek to address issues related to food security, human rights, labour migration, and investment in rural communities. Other organisations, such as Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières), seek to address major healthcare issues in refugee and IDP communities by providing healthcare for them and providing aid where there are significant health gaps. Conflict-related issues, especially within the context of Ethiopia’s internal conflicts, often attract the attention of human rights organisations such as Human Rights Watch and the UN Security Council. Such organisations work to ensure the rights of migrants and citizens across Ethiopia while combating the prevalence of human rights violations in the country, especially cases involving internationally displaced peoples and migrants.

Abebe, T. 2018a. Mutual benefits of Ethiopia’s refugee policy: Investing in migrants means investing in Ethiopians – and this is setting a global example. Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/mutual-benefits-ethiopia-s-refugee-policy-investing-migrants-means-investing

Abebe, T. 2018b. Ethiopia’s refugee response: Focus on socio-economic integration and self-reliance. Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved from: https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/ear19.pdf

Agence France-Presse (AFP). 2018. Ethiopia lifts ban on domestic workers moving overseas. Arab News. Retrieved from: https://www.arabnews.com/node/1237981

Ayalew, M., Aklessa, G. & Laiboni, N. 2019. Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW) | Women’s labour migration on the African-Middle East corridor: Experiences of migrant domestic workers from Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.gaatw.org/publications/Ehhiopia_Country_Report.pdf

British Broadcasting Cooperation (BBC). 2019. Ethiopia Country Profile. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13349398

Bundervoet, T. 2017. World Bank | Internal Migration in Ethiopia Evidence from a Quantitative and Qualitative Research Study. Retrieved from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/428111562239161418/pdf/Internal-Migration-in-Ethiopia-Evidence-from-a-Quantitative-and-Qualitative-Research-Study.pdf

Cenfri. 2018. Exploring barriers to remittances in the Sub-Saharan Africa: Remittances in Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://cenfri.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Barriers-study-volume-4-Remittances-in-Ethiopia_November-2018.pdf

CGTN Africa. 2019. Ethiopia-Djibouti railway hailed for impact on region’s import-export operations. Retrieved from: https://africa.cgtn.com/ethiopia-djibouti-railway-hailed-for-impact-on-regions-import-export-operations/

CIA World Factbook. 2020. Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/et.html

CIA World Factbook. 2025. Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/ethiopia/

Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Proclamation No. 1/1995, 21 August 2005. Retrieved from: https://ethiopianembassy.be/wp-content/uploads/Constitution-of-the-FDRE.pdf

Crisis Watch. 2019. Global Trends: Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.crisisgroup.org/crisiswatch/november-alerts-october-trends -2019#ethiopia

Degu, T.A. 2021. Reversing medical brain drain in Ethiopia: Thinking beyond restrictive measure. Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies, 8(2):33-46. Retrieved from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/mjas/article/view/208460/196506

Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM). 2018. Migration Flows in the Horn of Africa and Yemen. IOM. Retrieved from: https://migration.iom.int/data-stories/migration-flows-horn-africa-and-yemen

Endris, E. & Kassegn, A. 2021. Review on determinants of internal-migration in Ethiopia. Arts and Social Sciences Journal, 12(1):1-5. Retrieved from: https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/review-on-determinants-of-internalmigration-in-ethiopia.pdf

Eshetu, F., & Mohammed, B. 2017. Dynamics and determinants of rural-urban migration in Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 9(12):328-340. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/322157485_Dynamics_and_determinants_of_rural-urban_migration_in_Southern_Ethiopia

European Commission. 2019a. Ethiopia – Eritrean Refugee Influx, Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-eritrean-refugee-influx-dg-echo-unhcr-nrc-echo-daily-flash-26-september

European Commission. 2019b. Ethiopia Migration Profile. Retrieved from: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC115069/mp_ethiopia_2019_online.pdf

Ezra, M. & Kiros, G. 2001. Rural Out-Migration in the Drought-Prone Areas of Ethiopia: A Multi-Level Analysis. International Migration Research, 35(3):749-771. Retrieved from: http://mgsog.merit.unu.edu/ISacademie/docs/CR_ethiopia.pdf

Floodlist. 2021. Ethiopia – Deadly flash floods in Addis Ababa. Retrieved from: https://floodlist.com/africa/ethiopia-floods-addis-ababa-august-2021

Fransen, S., & Kuschminder, K. 2009. Migration in Ethiopia: History, Current Trends and Future Prospects. Maastricht Graduate School of Governance. http://mgsog.merit.unu.edu/ISacademie/docs/CR_ethiopia.pdf

Gebre, A.G. 2020. Ethiopia’s Tigray crisis: Causes implications and way forward. Retrieved from: https://www.politik.uni-kiel.de/de/professuren/vergleichende-politikwissenschaft/forschungsprojekte/abiyot2020

Global Compact on Refugees. 2024. Revitalizing Refugee Protection: How the Global Compact effectively complements the 1951 Geneva Convention. Retrieved from: https://globalcompactrefugees.org/news-stories/revitalizing-refugee-protection-how-global-compact-effectively-complements

Human Rights Watch. 2019. Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/ethiopia

Human Rights Watch. 2020. Ethiopia: Events of 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/ethiopia

Human Rights Watch. 2022. “We will erase you from this land”: Crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing in Ethiopia’s Western Tigray Zone. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2022/04/06/we-will-erase-you-land/crimes-against-humanity-and-ethnic-cleansing-ethiopias

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2025. Country profile: Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/ethiopia/

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2017. Promote Effective Labour Migration Governance in Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40africa/%40ro-abidjan/%40sro-addis_ababa/documents/publication/wcms_569654.pdf

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2021. ILO FAIRWAY supports returning Ethiopian migrant workers. Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/africa/media-centre/news/WCMS_802563/lang--en/index.htm

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019a. Fatal Journeys Volume 4: Missing Migrant Children. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/fatal-journeys-volume-4-missing-migrant-children

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019b. IOM, UNICEF Strengthen Partnership to Respond to Needs of Migrant Children. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/news/iom-unicef-strengthen-partnership-respond-needs-migrant-children

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019c. Number of Ethiopian Returnees Assisted by IOM on Track to Double in 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/news/number-ethiopian-returnees-assisted-iom-track-double-2019

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2023. Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/DTM%20Ethiopia%20National%20Displacement%20Report%2015_online.pdf

Institute for Security Studies (ISS). 2018. Mutual benefits of Ethiopia’s refugee policy. Retrieved from: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/mutual-benefits-of-ethiopias-refugee-policy

International Bar Association. 2023. Migration crisis: Attacks on Ethiopian refugees at Saudi border raise serious human rights concerns. Retrieved from: https://www.ibanet.org/Attacks-on-Ethiopian-refugees-Saudi-border#

Maastricht School of Governance. 2017. Ethiopia Migration Profile. Retrieved from: https://www.merit.unu.edu/publications/uploads/1517477021.pdf

Marchand, K., Reinold, J., & Silva, R.D. 2017. Study on Migration Routes in the East and Horn of Africa. Maastricht Graduate School of Governance. Retrieved from: https://i.unu.edu/media/migration.unu.edu/publication/4717/Migration-Routes-East-and-Horn-of-Africa.pdf

Migration Data Portal. 2019. Migration data in Eastern Africa. Retrieved from: https://migrationdataportal.org/regionalEthiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/country-resource/ethiopia

Migration Policy Institute (MPI). 2007. Beyond Regional Circularity: The Emergence of an Ethiopian Diaspora. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/beyond-regional-circularity-emergence-ethiopian-diaspora

National Legislative Bodies / National Authorities. 1995. Security, Immigration and Refugee Affairs Authority Establishment Proclamation No.6/1995. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/70034/95226/F1306988142/ETH70034.pdf

National Legislative Bodies / National Authorities. 2003. Ethiopia: Immigration Proclamation No. 354/2003 of 2003. https://www.refworld.org/docid/505c72002.html

National Legislative Bodies / National Authorities. 2019. Ethiopia: Proclamation No. 1110/2019. https://www.refworld.org/docid/44e04ed14.html

Research and Evidence Facility (REF). 2016. The Lure of the City: Synthesis report on rural to urban migration in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda. Retrieved from: https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/ref-hornresearch/files/2020/02/Lure-of-the-City.pdf

Terrazas, A.M. (2007). Beyond regional circularity: The emergence of an Ethiopian diaspora. Migration Information Source, Washington, DC. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/beyond-regional-circularity-emergence-ethiopian-diaspora

Tesso, G. 2019. Climate Change, Natural Disaster and Rural Poverty in Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2019/03/Climate-Change-Natural-Disaster-and-Rural-Poverty-in-Ethiopia-by-Gutu.pdf

United Nations (UN). 2019. UN Data 2019. Retrieved from: http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?q=ethiopia&d=PopDiv&f=variableID%3a12%3bcrID%3a231#PopDiv

UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2018. Humanitarian Needs Overview: Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2019. International Migrant Stock Country Profile: Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/countryprofiles.asp

UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2017. http://data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EDULIT_DS

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2018. Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF) Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/65916

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019a. UNHCR welcomes Ethiopia law granting more rights to refugees. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2019/1/5c41b1784/unhcr-welcomes-ethiopia-law-granting-rights-refugees.html

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019b. Additional provisions within the revised national refugee law in Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/additional-provisions-within-revised-national-refugee-law-ethiopia

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019c. Global Trends: Forced Displacement 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5d08d7ee7/unhcr-global-trends-2018.html.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2001-2022. Fleeing unaccompanied: Healing the suffering of children who have lost everything. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/hk/en/unaccompanied-children

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Dozens of refugees enter Sudan after renewed violence in Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/dozens-refugees-enter-sudan-after-renewed-violence-ethiopia#

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023. Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/eth/235

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/eth

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA). 2019. Ethiopia Humanitarian Needs Overview 2019. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-humanitarian-needs-overview-2019

UN Women. 2021. Trafficked and returned: Supporting migrant women survivors in Ethiopia during COVID-19. Retrieved from: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2021/12/trafficked-and-returned-supporting-migrant-women-survivors-in-ethiopia-during-covid-19

USAID. 2021. On one year of conflict in Northern Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/nov-4-2021-one-year-conflict-northern-ethiopia

US Department of State. 2019. Trafficking in Persons Report – Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Trafficking-in-Persons-Report.pdf

US Department of State. 2023. Trafficking in person report: Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/ethiopia/

US Department of State. 2024. Trafficking in person report: Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/ethiopia/

Voice of America (VOA). 2023. Ethiopian migrants stuck in Yemen as repatriation pauses. Retrieved from: https://www.voanews.com/a/ethiopian-migrants-stuck-in-yemen-as-repatriation-pauses-/7270573.html

Walk Free Foundation. 2019. Ethiopia’s New Migration Policy: A Positive Step but Continued Scrutiny needed. Retrieved from: https://www.minderoo.com.au/walk-free/news/ethiopias-new-migration-policy-a-positive-step-but-continued-scrutiny-needed

World Bank. 2023. Personal remittances, received (current US$). Received from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT

World Bank Group. 2019. Ethiopia. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ethiopia/overview

World Bank Group. 2015. Ethiopia Poverty Assessment 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/publication/ethiopia-poverty-assessment

Zekarias, A.Y. 2023. The Nature and Patterns of International Migration of Ethiopia. In: Muenstermann, I., ed. The Changing Tide of Immigration and Emigration During the Last Three Centuries. London: IntechOpen. 19 pp.

Zerihun, M.F. 2020. Remittances and economic growth: Evidence from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda. African Human Mobility Review, 6(3):6-27. Retrieved from: https://scielo.org.za/pdf/ahmr/v6n3/01.pdf