Historical Background

Historical Background

Historically, migration patterns into the current-day Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) were informed by the hunter-gatherer nature of society, European exploration, missionary work, and expansion of the slave trade. Initially a personal colony of King Leopold II of Belgium, the DRC was exploited for the extraction of rubber, minerals, and oil. In 1907, the local population officially handed Belgium the territory (current-day DRC) due to the abuse and exploitation the people of Congo experienced, which resulted in the death and maiming of millions under the King’s rule. During the Belgian colonial era, the number of Belgians living in the DRC rose from 1,500 to 17,000 in 1930 and to 89,000 in 1959 (Flahaux & Schoumaker, 2016).

Due to its strategic geographical position, the DRC has played a crucial role in migratory movements in Africa, being at the same time a country of origin, destination, and transit for millions of people since its independence. Unfortunately, an accurate and updated analysis of the migration patterns is still not possible because of the lack of reliable data and the often-undocumented nature of immigration to the country. After its independence and throughout the 1970s, the DRC became an attractive destination for working migrants from African countries and Eastern countries (Lebanon and India) looking for employment, especially in the mining sector. After the 1973 oil crisis, immigration slowed down and continued to do so as the political situation worsened. According to the United Nations Population Division (UNPD, 2008), the number of immigrants has been dropping since 1995. During this period, the country was turned into an immense refugee camp hosting people fleeing from Rwanda, Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, and Uganda. It is important to note that the country has largely been considered a transit point to other destinations, such as South Africa, which are considered much safer and seemingly offer better opportunities.

The Second Congo War (1998-2003) reversed the migration trend, leading to massive internal displacements and urging many Congolese to leave their country. Yet, recent international commercial agreements between Kinshasa and Beijing have increased the presence of Chinese immigrants in the DRC. These immigrants operate in the mining sector, work for infrastructure projects, or run businesses that hold the potential to improve the economic conditions of the country (Flahaux & Schoumaker, 2016).

The profile of Congolese emigrants has undergone significant changes in recent years. In the 1960s and 1970s, they were long-term working migrants heading to Belgium and France. However, during the 1990s, they were mostly asylum seekers and refugees fleeing to other African countries, often without being registered. Therefore, beyond the official figures accounting for Congolese migration, especially during the two Congo wars, a massive exodus of people has remained unrecorded.

Migration Policies

Migration Policies

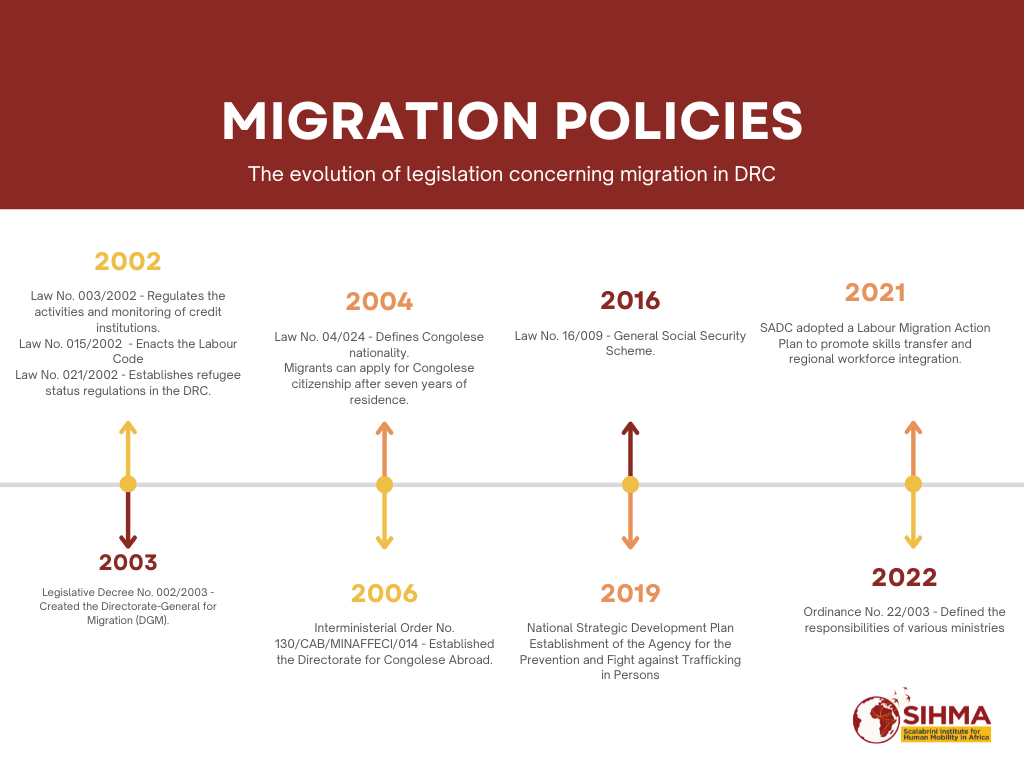

So far, the DRC has acceded to international conventions on migration. These include the UN Convention on the Status of Refugees (1956 and 1967 protocols), the 1969 OAU Refugee Convention, the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (1993), the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (1996), and the Protocols against the Smuggling of Migrants and Human Trafficking (2005). The DRC also signed the Kampala Convention on IDPs in Africa (2016). In addition to that, the government of the DRC has signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1976) and ratified the 1990 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The Constitution of 2005 recognises the rights of migrants in terms of section 32 and grants further rights associated with asylum seekers and refugees in section 33. Yet, the government has never developed a clear and efficient migration policy and lacks a solid legal framework on migratory issues. Act No. 23-96 of June 1996 states the terms of entry, stay, and leave for foreigners.

Timeline of Migration Policies in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Source: SIHMA

In 2002, the government passed a national refugee law (Law No 021/2002 of 16 October 2002) establishing the National Refugee Commission (CNR – Commission Nationale pour les Réfugiés) to process asylum applications and ensure the protection of refugees (UNHCR, 2013). In the same year, another law (No. 036/2003) established the main institutions regulating migratory policies, namely the Central Directorate of the Border Police to the Congolese National Police (for the control of migratory movements and borders) along with the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (issuing permits to working immigrants) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (issuing passports and visas and, since 2006, monitoring Congolese emigrants). Moreover, Law No. 036/2002 of 28 March 2002 provides for the designation of Services and Public Bodies authorised to act at the borders of the DRC. The Law designates the following government services: the General Directorate of Migration (DGM), the Customs and Excise Office (OFIDA), the Congolese Control Office (OCC), the Public Hygiene Service, and the then new Central Directorate of the Border Police of the Congolese National Police which supports these four services and ensures the protection and physical surveillance of the borders. Together, these five services ensure integrated border management in accordance with their specific mandates.

Despite various institutions dealing with migration and refugee issues in the DRC, the legal framework still presents some gaps, and poor coordination among the different departments and ministries remain a key challenge for the development of an effective migration policy.

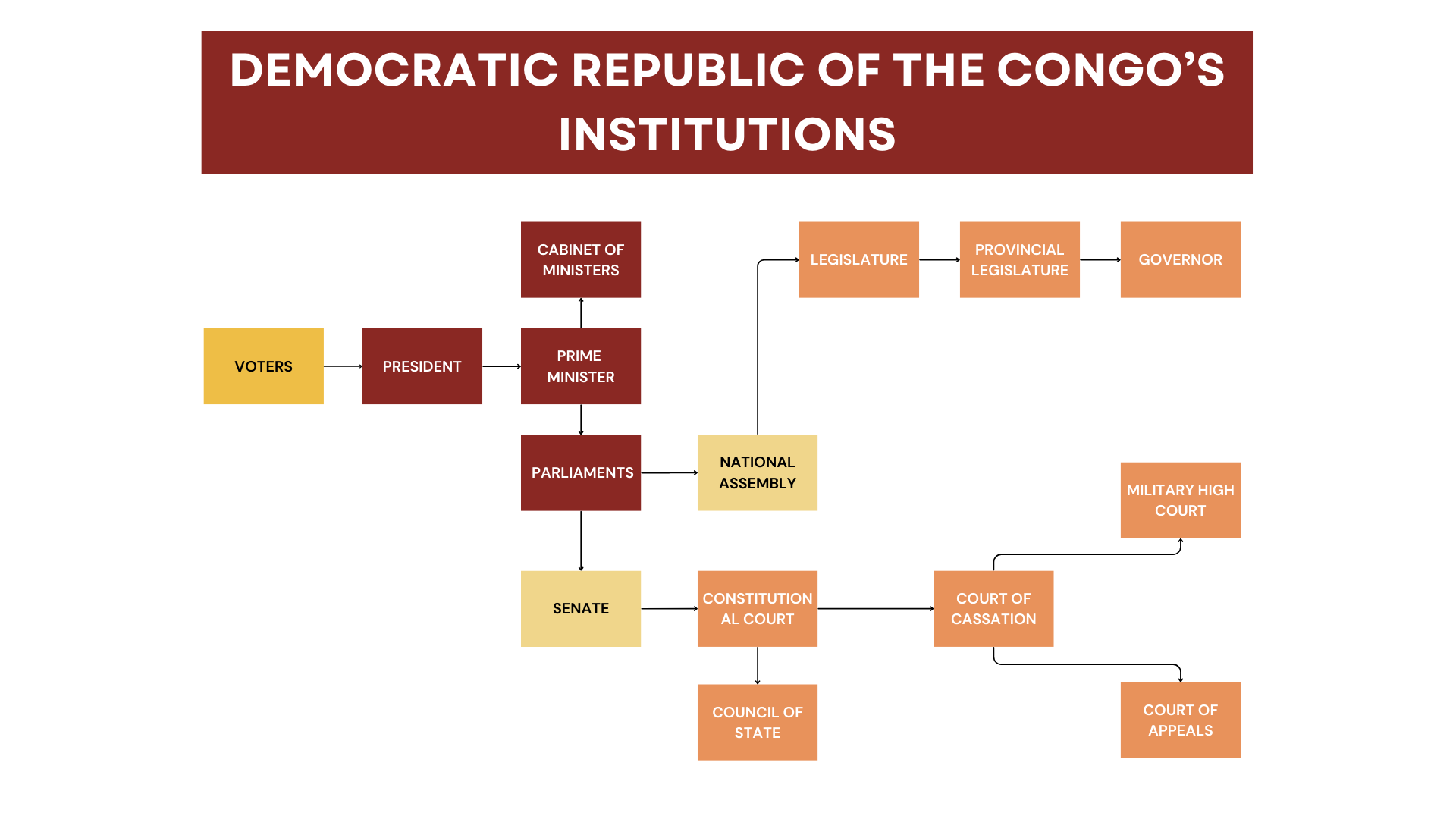

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

-

Ministry of the Interior and Security: The Ministry of the Interior and Security is responsible for the identification and census of the population; it grants refugee status in collaboration with the National Refugee Commission, and it also deals with border control policy. In addition, the Ministry of the Interior and Security assists refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and other vulnerable groups of people. The General Directorate for Migration (DGM – Direction Générale des Migrations) within the Ministry of the Interior and Security is the main government institution dealing with migration policies. As such, the DGM controls and regulates movements of the national and foreign population, issues passports and visas, coordinates border police, collaborates with other international organisations, and publishes internal annual reports.

-

Vice-Ministry for Congolese Nationals Abroad: Since 2006, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs appointed a Vice-Ministry for Congolese Nationals Abroad to monitor emigration issues (Diaspora Engagement Mapping, 2020). The Vice-Ministry of Congolese Abroad plays an increasingly important role in the synergy of action between the diaspora and the country of origin (ibid). Shortly after appointing the Vice-Ministry, the Directorate for Congolese Nationals Abroad was established (ibid). Additional actors were clarified in accordance with Law No. 036/2002 of 28 March 2002. This law provides for the designation of Services and Public Bodies authorised to act at the borders of the DRC and the law determines the services authorised at the borders of the DRC (General Directives in terms of Law No. 036/2002). Accordingly, the General Directorate of Migration (DGM) operates in reserved areas at border crossings and borders, focusing on the management of migratory flows and counterintelligence (ibid).

-

The Customs and Excise Office (OFIDA): In accordance with the Ordinance Law 079/114 of 15 May 1979, this office deals with the following: customs clearance formalities for import and export goods; general surveillance of exits from the customs area as well as the unloading of goods; control at the outset of commercial exports made by migrants; formalities regarding the obligation to declare goods; the application and collection on arrival of duties and taxes on goods; control aimed at detecting illicit traffic and prohibited imports; control of warehouses and customs clearance areas; and customs clearance of packages imported by individuals (ibid).

-

The Congolese Control Office (OCC): This office intervenes in control at the place of loading and unloading of the quality, quantity, and prices of goods and products exported and imported and the certification of the condition of goods and products as to their appropriation for consumption. The Public Hygiene Service takes care of border health control (ibid).

-

The Central Directorate of the Border Police to the Congolese National Police: This directorate is responsible for ensuring the security and maintenance of public order at border crossing points; managing physical border surveillance to fight against irregular migration and organised cross-border crimes; channelling migrants to official border crossing points; providing support to all other services in case of problems in order to restore public order; and searching for common law offenses (ibid).

-

The Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare: This Ministry issues work permits for migrants and deals with the employment policy.

-

The Ministry of Justice: This Ministry regulates issues of nationality and naturalisation and collaborates with Interpol forces.

-

The Ministry of Social Affairs: This Ministry deals with the reintegration of child soldiers and other vulnerable groups. It is also responsible for humanitarian issues.

The Democratic Republic of Congo Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

From 1999 to 2009, movement in the DRC was marked by two factors: i) forced displacement during the wars and economic crisis, and ii) the exploitation of natural resources (Ngoie & Lelu, 2009). While the former urged people to move from rural to urban areas like Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, and Goma where they could be employed in the informal sector, the latter reversed the migratory route from urban to rural areas in Pwelo, Dilolo and Kambove where the search for gold and other minerals became the predominant activity for migrants (ibid).

The past two decades have been characterised by rapid urbanisation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, particularly in Kinshasa. Despite the absence of current census data, Kinshasa remains one of the largest cities in Africa after Lagos and Cairo (Anglewicz et al., 2017). It is projected to become the largest megacity in Africa by 2030 (Batana et al., 2021). According to the World Development Indicators (WDI), as cited by Batana et al. (2021), the DRC’s urban population doubled from 16.5 million in 2000 to 35.7 million in 2017, reflecting a 1.1 million annual increase with an increase in the urbanisation rate from 35% to 44% during the same period. The armed conflict that has plagued the DRC for centuries has limited the free movement of people to other parts of the country – hence the concentration of people in urban areas where there is some level of perceived security.

Internally Displaced Persons, Conflicts & Disaster

Internally Displaced Persons, Conflicts & Disaster

By the end of December 2022, 5.7 million people were internally displaced as a result of conflict and disaster in the Democratic Republic of Congo (IDMC, 2023). However, by April 2023, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, as cited by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID, 2023), the number of internally displaced persons had increased to 6.2 million. The increment is greatly informed by the presence of armed groups fighting against the state. Other sources of internal displacement include the outbreak of epidemics (cholera, measles, and Ebola) and acute food insecurity. Although the figures have dropped to slightly below 4 million according to a 2024 report by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, it remains the second highest figure globally after Sudan.

Conflict remains the main source of internal displacement in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Sources of conflict/violence include military operations against non-state armed groups, clashes between groups, and inter-communal violence. In 2023, the country recorded its second-highest figures on conflict-related displacement: 3.8 million compared to the 4 million (the highest) recorded in the previous year (2022) (IDMC, 2023; IDMC, 2024). The eastern provinces of Ituri and North and South Kivu recorded the highest number of conflict-related displacements (IDMC, 2024).

In terms of disaster-related displacements, the country experienced a decline from 423,000 in the previous reporting year (2022) to 133,000 in the current reporting year (2023) (IDMC, 2023; IDMC, 2024). Disaster-related displacements in the current reporting year (2023) were triggered by floods, storms, and landslides in the provinces of Central Kasai, Haut-Katanga, Haut-Uele, Ituri, Kwango, Kwilu, Maniema, North Kivu, Tanganyika, and Tshopo (IDMC, 2024). Other causes of disaster-related displacements include landslides, earthquakes, strong winds, and volcanic eruptions. Although disasters contribute to displacements in the country, the antagonism between the different warring armed groups is the main cause of heightened levels of internal displacements in the country.

Immigration

Immigration

The economic endowment of the Democratic Republic of Congo remains one of the indisputable pull forces of international migrants in the country. In 2010, the international migrant stock was estimated to be 589,000. In 2015, it was estimated to be 810,000, in 2020, it stood at 952,900 and in 2024, it increased to 1.1 million representing a 0.9% to 1% share of the total population (UN DESA, 2025). Though there has been a slight increase from 2015 to 2024, it is low as a proportion of the population.

The country is endowed with vast natural resources. Yet, its resources are being looted by a few at the expense of millions of innocent men, women, and children abandoned in extreme poverty. For example, according to the Global Witness report, as indicated by the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (2018), between 2013 and 2015, more than $750 million of mining revenues paid by companies to the state bodies was lost to the treasury. This mismanagement and plundering of state resources has constrained development programmes, making the country unattractive to immigrants, especially economic migrants. Most of the immigrants in the DRC come from the Central African Republic, Rwanda, Angola, South Sudan, and Burundi (UN DESA, 2025).

Data on migration in the country is difficult to verify because of irregular and unregistered border crossings, informal and unregistered labour practices, and outdated census statistics. Moreover, those who are self-employed often work in the informal sector, making it difficult to account for them in migration statistics. Also, no census has been conducted in the DRC since 1984.

Female Migration

Female Migration

In the DRC, male and female immigration patterns into the country have mostly been equal, with female immigrants slightly dominating the immigrant population. Though female immigrants as a percentage of the immigrant population stock were at its lowest in 1995 at 50.4%, the number of female immigrants that year was the highest (915,768) (UN DESA, 2021).

This is because the number of immigrant stock that year was relatively high compared to the other years. For example, despite an increase in the percentage of the female immigrant stock in 2020 (51.8%), the female immigrant stock was only 493,800, almost two times less than the 1995 figures. It is also important to note that the female stock of the immigrant population has been fluctuating between 50.4% and 51.8% from 1990 to 2019 (ibid).

Children

Children

According to the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA, 2021), the immigrant stock of children in the DRC younger than 18 years has been stable between 1990 and 2015 at 27.4% and 27.5% of the immigrant population stock. In 2020, the immigrant stock of children as a percentage of the immigrant population stock declined to 17.4% (ibid). The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF, 2021) indicated that, as a result of militia attacks, there are more than 5 million displaced people in the DRC, about 3 million of which are children. According to Save the Children (2022), children in the DRC face several challenges. With more than 73% of people living in poverty, 91 out of 1,000 children die before their fifth birthday, 43% of children have stunted growth due to severe malnutrition, 38% of children engage in child labour, and 21% of girls aged 15 to 19 are married. Another challenge facing children in the DRC is the forced conscription of child soldiers by militia groups. Although there is no precise data on the number of child soldiers in the DRC, UNICEF (2018) posits that in the Kasai region alone, there are between 5,000 and 10,000 child soldiers. The volatile political situation in the country increases the vulnerability of children, particularly child migrants.

Refugees and Asylum seekers

Refugees and Asylum seekers

For decades, the Democratic Republic of Congo has maintained an “open-door policy” to refugees, welcoming and protecting refugees from other parts of the world. The number of refugees in the DRC reached a record of 1,433,800 in 1995 (UN DESA, 2021), and since then, it has dropped to below 600,000. In November 2024, there were 519,239 refugees and 965 asylum seekers in the DRC (UNHCR, 2024a). The top countries of origin of refugees in the DRC in November 2024 were the Central African Republic (206,701), Rwanda (204,159), South Sudan (56,114), and Burundi (51,265) (ibid).

Although the DRC has an encampment policy for refugees, 75% of refugees and asylum seekers live outside the refugee camps, 2% live in urban areas (mainly Kinshasa and Lubumbashi), and 23% in 10 planned settlements (camps) (UNHCR, 2024b). Refugees from the Central African Republic are located mostly in the North and South Ubangi, Bas-Uele, and Ituri provinces while those from South Sudan are primarily located in the Haut-Uele and Ituri provinces. Rwandan refugees are mainly located in North Kivu and South Kivu while refugees from Burundi are mainly located in the South Kivu province (UNHCR, 2019-2020). As a result of militia attacks in provinces such as North Kivu, South Kivu, and Ituri, the number of refugees located in urban areas such as Kinshasa, Goma, Bukavu, and Lubumbashi is increasing.

Despite the uncertain political situation in the country, the DRC’s geographical position provides a passage for thousands of refugees escaping the conflict and insecurity in neighbouring countries such as Burundi, Rwanda, Angola, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan. In 2002, in response to the inflow of asylum seekers in the DRC, the government created the National Refugee Commission to deal with asylum applications (UNHCR, 2019-2020). By law, refugees are granted the same basic rights as nationals in the DRC. However, it is always problematic to assist and monitor refugees because of the country’s political instability. Although the DRC is a refugee-receiving country, the number of refugees from the DRC is also growing. There is a geopolitical irony in the tension between the reception and open hosting of refugees by a country that has a growing number of refugees fleeing its territory.

According to the UNHCR (2022b), there were 403,775 Congolese refugees in 2018. In 2022, the number of Congolese refugees has more than doubled to 960,441 (ibid). Most of the refugees from the DRC live in neighbouring African countries like Angola, Burundi, the Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania, and Zambia.

Emigration

Emigration

The DRC is one of the poorest countries in the world, although it is rich in natural resources. The country is characterised by political unrest, poor public infrastructure, and a poor road network. Most of the emigrants want to escape ongoing conflicts and find better living conditions in other countries. The number of Congolese emigrants has increased significantly on an annual basis since 1995. According to UN DESA (2025), emigrants numbered 559,800 in 1995, 862,100 in 2000, and 1.1 million in 2005. These numbers kept increasing in 2010 (1.3 million), 2015 (1.6 million), and in 2020 (1.9 million) to reach 2.1 million in 2024 (ibid). Different figures were provided by Ngoie and Lelu, who drew on results from the 1995-2005 census carried out by the Development Research Centre at Sussex University, which reported that the number of Congolese emigrants was around 821,057. On the other hand, in 2007, the Ministry of Home Affairs estimated that the total number of emigrants was around 3,000,000. These anomalies make it difficult to gain a clear understanding of the migratory patterns and an accurate profile of Congolese emigrants.

In 2013, the Congolese migrant stock according to destination country was reported to be as follows: 266,319 emigrants to the Republic of Congo, 175,738 to Rwanda, 169,074 to Uganda, 148,852 to Burundi, and 62,172 to France (UNICEF, nd). However, according to Countryeconomy.com (2019), the top five destinations for Congolese migrants were France (76,499), South Africa (34,445), Tanzania (22,434), Gabon (16,194), and Mali (11,849). In 2019 the total percentage of Congolese working-age migrants was 71.4%, with 1.7 million people who could potentially be employed or self-employed, especially in the informal sector (where migrants mostly find work) but also in light and heavy industry, health care, and retail businesses.

Unfortunately, no accurate data is available on unemployed migrants. The 2009 Human Development Report shows that 35.5% of Congolese emigrants have tertiary education, 32.5% have secondary or post-secondary education, and 25% have less than secondary education. The country’s political instability and the exploitation of its resources that do not adequately benefit its citizenry make emigration one of the ways of escaping economic hardship.

Labour Migration

Labour Migration

Despite the country’s political and economic instability, ethnic conflict, and ongoing wars, its diverse mineral resources – like cobalt, zinc, uranium, diamonds, and gold – continue to attract international migrants, including low-skilled and irregular immigrants from neighbouring African countries and multinational corporations. As a member state of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), which recently adopted a new labour action plan that progressively seeks to eliminate obstacles to the free movement of capital and labour, the DRC is committed to welcoming migrant labour from other countries in the region. Countries outside the regional formation with labour immigrants in the DRC include China, Ukraine, Lebanon, India, and Mexico.

Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking

The DRC is a source, transit, and destination country for human trafficking and was upgraded from the Tier 3 to Tier 2 watchlist (US Department of State, 2024). Men, women, and children are at risk of forced labour and sex trafficking, mostly inflicted by the armed groups that still control some areas, especially in the eastern region (ibid). Common forms of exploitation include forced labour and debt bondage. Women and girls are used for forced prostitution and marriages and as domestic servants. Children are employed in agriculture, mining, smuggling, and begging (ibid). Children are also conscripted into the army as combatants, spies, or human shields (ibid).

Human trafficking is prevalent in the DRC, with 3,107 documented cases in which children escaped from armed groups in the country in 2019 (Borgen Project, 2020). In April 2019, the Agency for the Prevention and the Fight Against Trafficking in Persons (APLTP) was established as the national coordinating body for anti-trafficking (US Department of State, 2023).

The government, in partnership with NGOs, identified and referred to services 174 trafficking victims (69 sex trafficking victims, 73 labour trafficking victims, and 32 victims of unspecified forms of trafficking) (US Department of State, 2024). Also, the government initiated 90 investigations (58 for sex trafficking, 19 for labour trafficking, and 13 for unspecified forms of trafficking), initiated the prosecution of at least 21 defendants, prosecuted 17 defendants, and obtained convictions for two traffickers (ibid). The challenges that impede the government's ability to deal with human trafficking in the DRC include difficulties in identifying victims and officials conflating trafficking with other crimes (ibid). Additionally, with nine neighbouring countries, Congolese borders are difficult to monitor, and police surveillance is ineffective. Angola and Uganda allow refugees and asylum seekers to enter informally, that is without being accounted for. Traffickers use the opportunity to traffic their victims without any police intervention.

In 2018, there was further evidence of some national army forces being involved or complicit in human trafficking (US Department of State, 2019). For instance, from January to August 2018, reports indicate that at least 893 women and girls were victims of sexual and gender-based violence, with primary perpetrators including police, intelligence agents, armed groups, and the Congolese National Army (FARDC), which worked with proxy militias that recruited and used child soldiers (ibid). Also, the FARDC continued to collaborate broadly with the Bana Mura proxy militia, which used at least 64 children in sexual slavery during the 2018 reporting period (ibid).

In the following year (2019), the government increased prosecutions and investigations of trafficking cases, particularly sex trafficking and forced labour crimes that had previously generally not been addressed in the justice system (US Department of State, 2020). The government convicted a former colonel in the FARDC for trafficking crimes and ordered the leader of an armed group and two accomplices to pay restitution to more than 300 victims of sexual enslavement and other crimes (ibid). However, in 2024, UN experts re-echoed the same sentiment on the increasing numbers of people trafficked for sexual exploitation (UN, 2024). The involvement of some government officials in the illicit practice of human trafficking in the DRC highlights the endemic nature of the crisis in the country and calls for strong political will from the government to fight this crime.

Remittances

Remittances

Despite its wealth of mineral resources, the Democratic Republic of Congo remains one of the poorest countries in sub-Saharan Africa and the world. The World Bank estimated that 73% of the Congolese population, about 60 million people, live on less than $1.90 a day (World Bank, 2022). Remittances, therefore, constitute a lifeline in the DRC as they provide many households with a level of financial security. The unavailability of data on financial flows and the informal channels used to facilitate most financial flows make it very difficult to determine the actual remittance flow in the DRC.

According to Sumata and Cohen (2018), depending on different sources, remittance flow into the DRC in 2008 stood at $130 million. In 2009, it stood at $2.3 billion, and in 2011, it jumped to $9.3 billion. The World Bank, as cited by FinDev Gateway (2020), estimates that the value of remittances in the DRC stood at $1.8 billion in 2019, constituting 3.7% of the country’s GDP. The most common uses of remittances in the DRC include satisfying basic needs and consumption, paying for education and health care, funding events (marriage, baptism, and funeral), purchasing land, building houses, and enabling business development (Sumata & Cohen, 2018). In a country where 73% of the population lives in poverty, migration and remittances remain a vital source of income for many migrant households.

Returns and Returnees

Returns and Returnees

Political instability, poor economic conditions, and restrictions on re-entering European countries are some of the factors that discourage emigrants from returning to the DRC. However, the government, in an attempt to create a linkage between the diaspora and their country of origin, established the Vice-Ministry of Congolese Nationals Abroad with its mandate to mobilise Congolese abroad for the development of the country and their integration into national life and to protect their rights abroad (European Union Global Diaspora Facility – EUDiF, 2020). A parallel institution, the Directorate for Congolese Nationals Abroad, was created shortly afterwards within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Despite this, many return programmes and policies are handled by international organisations, including repatriation initiatives.

International organisations such as the UNHCR continue to play a leading role in facilitating the return of Congolese migrants. For example, returning migrants benefit from a cash allowance, food and personal hygiene items, and family reintegration (Africa Renewal, 2023). In 2022, the UNHCR assisted about 600 Congolese who volunteered to return home from South Africa (UNHCR, 2022). At the same time, immigrants are also forcefully taken out of their host communities through deportation. Between 2009 and 2017, a total of 3,275 Congolese were deported from their host countries – the United Kingdom (1,085), Belgium (715), France (650), and Germany (265) (Alpes, 2019). Back in the DRC, returnees face legal, social, economic, and psychological challenges. Some returnees also face homelessness, social stigmatisation, mental health problems, arbitrary arrest, and detention (Migration Policy Institute, 2019). In addition, returnees may be separated from family members or loved ones who remain in the departed country and families in the homeland stop receiving remittances. The fact that increasing numbers of Congolese do not voluntarily return home but are being deported from their host countries indicates their unwillingness to return home as a result of recurrent political unrest in parts of the DRC, and the DRC’s dire economic situation.

International Organisations

International Organisations

Key international organisations dealing with migration in the DRC are the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and Doctors without Borders (MSF). The IOM aims to improve the collection of data on migratory movements and internal displacements as well as to better manage situations at the borders, where the majority of the population lives and where the presence of refugees and asylum seekers is more prevalent. In the DRC, the IOM has operated by assisting returnees and opposing human trafficking. The UNHCR deals mainly with refugees and IDPs and cooperates with government departments to host Congolese refugees worldwide. In addition, the UNHCR supports and invests in programmes that create opportunities for personal development, such as in the Mantapala settlement in Zambia where refugee women, including many Congolese women, were empowered and trained to become entrepreneurs and have access to markets and services. Doctors without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières – MSF) assists migrants fleeing disease and conflict in the DRC. In 2019, the MSF responded to the world’s largest measles epidemic, with 310,000 infected and 6,000 dead; aided women displaced as a result of gender-based violence; and provided shelter for those displaced as a result of inter-communal violence.

Africa Renewal. 2023. Angolan refugees return to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to build a new life. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/january-2023/angolan-refugees-return-democratic-republic-congo-build-new-life

Alpes, J. 2019. After deportation, some Congolese returnees face detention and extortion. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/after-deportation-some-congolese-returnees-face-detention-and-extortion

Anglewicz, P., Corker, J. & Kayembe, P. 2017. The fertility of internal migrants to Kinshasa. Genus, 73(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s41118-017-0020-8

Batana, Y.M., Masaki, T., Nakamura, S. & Vilpoux, M. E. V. 2021. Estimating Poverty in Kinshasa by Dealing with Sampling and Comparability Issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper.

Borgen Project. 2020. Human trafficking in DRC. Retrieved from: https://borgenproject.org/human-trafficking-in-the-drc/

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. 2018. We need to challenge the management of natural resources in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/blog/we-need-to-change-the-management-of-natural-resources-in-the-democratic-republic-of-congo/

CIA World Factbook. 2025. Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/congo-democratic-republic-of-the/

Countryeconomy.com. 2019. Republic of the Congo – International emigrant stock 2019. Retrieved from: https://countryeconomy.com/demography/migration/emigration/congo

European Union Global Diaspora Facility (EUDiF). 2020. Diaspora engagement mapping: Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://diasporafordevelopment.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CF_DRC-v.2.pdf

FinDev Gateway. 2020. Formalizing remittances for forcibly displaced people: Findings from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.findevgateway.org/blog/2020/09/formalizing-remittances-forcibly-displaced-people-findings-democratic-republic-congo

Flahaux, M. & Schoumaker, B. 2016. Democratic Republic of the Congo: A migration history marked by crises and restriction. Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/democratic-republic-congo-migration-history-marked-crises-and-restrictions

Floodlist. 2022. Democratic Republic of Congo – more deadly floods and landslides in Eastern Provinces. Retrieved from: https://floodlist.com/tag/democratic-republic-of-the-congo

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. A region on the move. Retrieved from: https://d2sby212evx72u.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/dtm/east_and_horn_of_africa_dtm_201905.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020. Migration data portal. Retrieved from: https://migrationdataportal.org/?t=2017&i=ctdc_origin_percfem2018&cm49=180

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2023. Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo

Migration Policy Institute. 2019. After deportation, some Congolese returnees face detention and extortion. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/after-deportation-some-congolese-returnees-face-detention-and

Ngoie, G. & Lelu, D. 2009. Migration en Republique Democratic du Congo: Profile National 2009. IOM. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/drc_profile_2009.pdf

Save the Children. 2022. Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.savethechildren.org/us/where-we-work/democratic-republic-of-congo

Sumata, C. & Cohen, H. 2018. The Congolese diaspora and the politics of remittances. Remittances Review, 3(2): 95-108. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328556373_The_Congolese_diaspora_and_the_politics_of_remittances

United Nations (UN). 2024. DRC: Alarming increase in trafficking for sexual exploitation: say experts. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/07/drc-alarming-increase-trafficking-sexual-exploitation-say-experts

UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2018. Thousands of children continue to be used as child soldiers. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/drcongo/en/press-releases/thousands-children-continue-be-used-child-soldiers

UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2021. DR Congo: Lives and futures of three million children at risk, UNICEF warns. Retrieved from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/02/1085182

UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF). N.d. Migration profile: Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://esa.un.org/miggmgprofiles/indicators/files/DRC.pdf

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2021. Profile: Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2025. Profile: Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2013. Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5283481a4.pdf

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019-2020. Democratic Republic of the Congo country refugee response plan. Retrieved from:https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/DRC%202019-2020%20Country%20RRP%20%28February%202019%29.pdf

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022a. Democratic Republic of the Congo Factsheet – January – March 2022. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/unhcr-dr-congo-factsheet-january-march-2022

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022b. Refugees and asylum seekers from DRC. Retrieved from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/drc

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022c. Homeward bound: Congolese refugees in South Africa opt to restart their lives in Kinshasa. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/afr/news/stories/2022/4/62603dee4/homeward-bound-congolese-refugees-in-south-africa-opt-to-restart-their.html

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024a. Refugees in the DRC. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/cod

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024b. The Democratic Republic of the Congo: Refugee policy review framework country summary as of 30 June 2023. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/democratic-republic-congo-refugee-policy-review-framework-country-summary-30-june-2023-update-summary-30-june-2023

US Department of State. 2019. Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-trafficking-in-persons-report-2/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/

US Department of State. 2020. Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1323521/download

US Department of State. 2023. Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo

US Department of State. 2024. Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/

USAID. 2023. Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #4 Fiscal Year. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/democratic-republic-congo-complex-emergency-fact-sheet-4-fiscal-year-fy-2023

World Bank. 2022. The World Bank in DRC. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/drc/overview

World Bank Group. 2021. Profiling living conditions of the DRC urban population: Access to housing and services in Kinshasa province. Policy Research Working Paper 9857. Retrieved from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/638901637330907469/pdf/Profiling-Living-Conditions-of-the-DRC-Urban-Population-Access-to-Housing-and-Services-in-Kinshasa-Province.pdf