Banner photo by Eva Blue on Unsplash

Historical Background

Historical Background

Migration to Ivory Coast (Cote d’Ivoire) can partly be traced as far back as the 13th century with people migrating from various parts of West Africa into the country. Before French colonisation, Ivory Coast was home to pre-colonial West African states such as Gyaaman, the Kong Empire, and the Baoulé, Anyi, and Sanwi Kingdoms (Bassey, 2011). Gyaaman was a medieval state of Akan located in current-day Ghana and Ivory Coast. Prior to independence, factors such as trade and trade routes, Islam, gold mines, agricultural activities, and wars influenced migration to Ivory Coast (ibid).

After independence, the government's open attitude towards immigrants during Houphouёt Boigny’s regime (1960-1993) played a significant role in encouraging the mass movement of people from other parts of West Africa to Ivory Coast. The country’s economic success from 1960 to 1979 attracted significant numbers of migrants from the sub-region. According to Blion, (1996), Ivory Coast represented the first migration country in West Africa and it was the region's primary destination for labour migrants. Despite its economic challenges and general decline in the economy, Ivory Coast constitutes one of the top ten migration corridors in western Africa and it is the number one destination for migrants in the West African region (Migration Data Portal, 2023). Hosting 2.1 million intra-African migrants in 2017, with an annual immigration growth rate of between 1.8% and 4.4%, except from 2000 to 2005 because of the military crisis, Ivory Coast is the second most important destination for international migrants on the African continent after South Africa (Traore & Torvikey, 2022). Abidjan, which is Ivory Coast’s largest city and its economic capital, represents one of the three main migration hub cities on the continent (Traore & Torvikey, 2022). In 2017, a total of 1.3 million migrants used the corridors between Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso (European Union, 2018). This makes it the second most important migration corridor in Africa and the number one destination for migrants within the West African region (Traore & Torvikey, 2022). Other corridors include Ivory Coast – Senegal and Ivory Coast – Mali (mostly labour migrants) (ibid). In 2013, Burkina Faso accounted for 60% of the immigrant population in Ivory Coast while Mali accounted for 16% (ibid).

After several years of an open and liberal migration policy that gave immigrants access to land, public jobs, and participation in local elections, the economic meltdown of the 1980s saw the prices of cocoa plummet and changed the political rhetoric towards immigrants as they were blamed for taking jobs from indigenous people and were consequently subjected to xenophobic attacks (Traore & Torvikey, 2022).

However, within Ivory Coast, emigration is on the rise, especially youth emigration. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2022), Ivory Coast is one of the top countries of origin of migrants who have reached the borders of Southern Europe. Irregular migration is a significant part of human movement from Ivory Coast, especially to Europe, which places the lives of migrants at risk. According to IOM (2020), 25,000 Ivorians have arrived in Italy irregularly by sea since 2016.

Migration Policies

Migration Policies

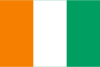

The most relevant pieces of legislation governing the identification of persons and the stay of foreigners in Ivory Coast relates to the migration policy: Law No. 2004-303 of 2004 and amending Law No. 90-437 of 29 May 1990 on the entry and stay of foreigners in Ivory Coast (IOM, 2019). Law No. 2016-1111 is Ivory Coast’s law against human trafficking while Law No. 2018-571 is aimed at combating the smuggling of migrants (ibid). The asylum law in Ivory Coast is still in draft form and is yet to be adopted. At the regional level, Ivory Coast is a member of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) which, among others, aims to facilitate the movement of people within the region and ultimately remove obstacles to the free movement of goods and services, capital, and labour.

Migrants have access to all public health and education services regardless of their status, although they are not eligible for medical schemes financed by the state. Tertiary education fees for international students are often higher than for nationals, depending on whether they are ECOWAS nationals or not (ibid). In line with the 1999 social security code, all workers in Ivory Coast, regardless of their nationality, are entitled to the benefits of the National Security Fund (Caisse Nationale de Prevoyance Sociale, CNPS) (ibid). Ivory Coast has agreements on the portability of retirement pensions with countries such as Burkina Faso. However, migrants do not have access to the government’s social housing programme and cannot be employed in the civil service. Ivory Coast grants nationality to migrants through marriage, naturalisation, declaration, and adoption (ibid).

Timeline of Migration Policies in Ivory Coast. Source: SIHMA

In 2013, Ivory Coast ratified the 2009 African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention), the 1954 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, and the 1961 United Nations Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. In 1998, the country ratified the 1969 Organisation of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. In 1961, it ratified the 1961 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Geneva Convention) and in 1991, it ratified the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). The implementation of these treaties will assist in providing durable solutions to people on the move.

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

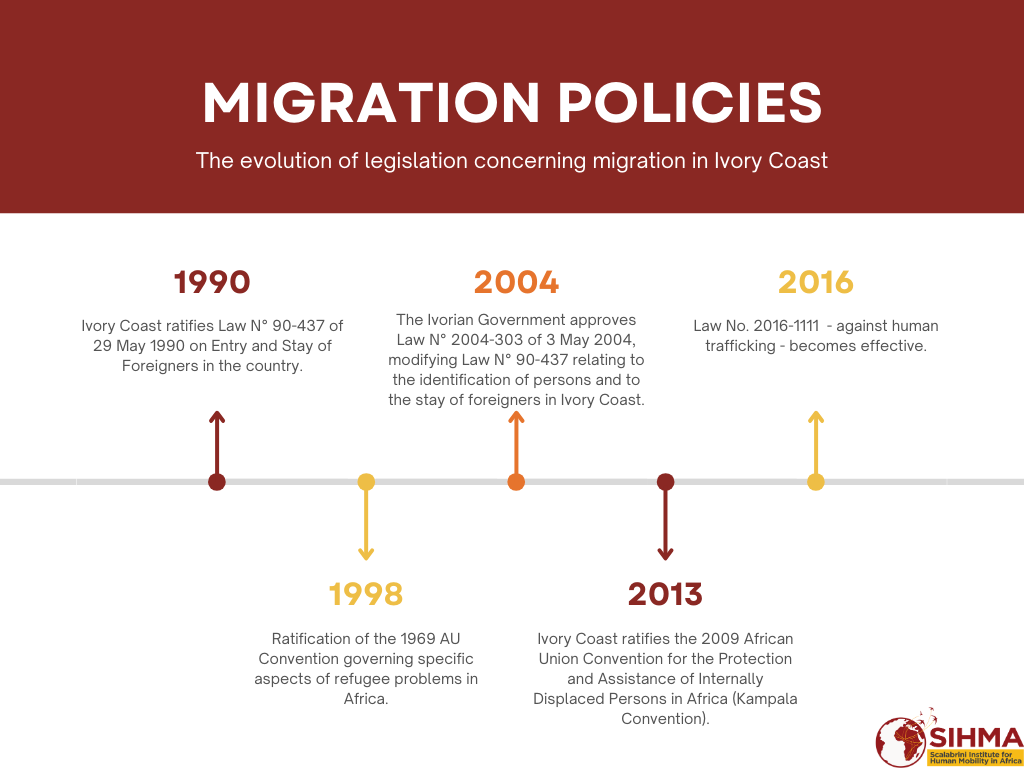

Several ministerial departments are charged with migrant-related issues in Ivory Coast:

-

The Ministry of Interior and Security oversees the management of migrant exit, entry, identification, and the formulation of migration policies.

-

The Ministry of Planning and Development oversees population policies.

-

The Ministry of Employment, Social Affairs, and Vocational Training provides work permits to foreign workers.

-

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs protects Ivorian nationals living abroad through consular services, and issues laissez-passer (permits).

-

The Ministry of African Integration and Ivorians Abroad oversees the management of the diaspora and African integration, which involves ECOWAS and other regional organisations.

Ivory Coast's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

Other ministerial departments working with migrants include the Ministry of Employment, Social Affairs and Vocational Training, and the Ministry of Solidarity, Family, Women and Children which helps to fight trafficking in persons (Rabat Process, 2018).

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

In the 1960s, internal migration was encouraged in Ivory Coast when the country enjoyed economic prosperity. Like in most parts of Africa, Ivory Coast experienced rural-urban migration. This movement contributed massively to the urbanisation of Ivorian cities, causing more than 50% of its population to live in cities (Dick & Schraven, 2021). The 1998 Ivorian census data indicates that there were 4,405,328 internal migrants in Ivory Coast, constituting 28.7% of the total population, and that most of these migrants live in cities (Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, 2017). The development of cities at the expense of rural areas triggers movement from rural areas to cities with the hope of gaining access to better opportunities. According to 2021 census data in Ivory Coast, the urban-rural population differential still skews in favour of the urban areas. According to the census data, 15,428,957 (52.5% of the population) reside in cities compared to 13,960,193 (47.5% of the population) who reside in rural areas (UN-Habitat, 2022). The four most populous cities, which are also overconcentrated according to the census report, are Abidjan (5,616,633), Bouake (832,371), Korhogo (440,926), and Daloa (421,879) (ibid). The overconcentration of people in cities causes housing challenges, increases the cost of living, increases poverty, and accelerates environmental degradation. The imbalance in the development plan of the country that prioritises urban areas causes a developmental deficit in rural areas which, in turn, puts strain on services in urban areas. Hence, there is a need for balanced development in the country.

Internally Displaced Persons, Conflict/ Violence & Disaster

Internally Displaced Persons, Conflict/ Violence & Disaster

Internal displacement in Ivory Coast is influenced mostly by conflict and violence. By the end of 2022, 302,000 people have been displaced by conflicts and violence while 2,500 have been displaced by natural disasters (IDMC, 2023).

Similar to the 2010-2011 post-presidential election violence, the 2020 presidential election has engulfed the country in yet more post-election violence, causing the internal displacement of thousands of Ivorians, mostly in the western region (UNHCR, 2020). In November 2020, the UN agencies and the Ivorian government had recorded 5,530 IDPs within the country (ibid). Women in Ivory Coast bear the brunt of internal displacement as displacement caused by conflict and violence exposes them to human rights violations and adversely affects their source of livelihood as conflict results in the destruction of production capital.

Natural disasters like torrential rain, flash floods, landslides, and earthquakes contribute to internal displacement in Ivory Coast. The Ivorian government adopted several instruments (for example, organising disaster relief) to provide assistance through the Ministry of Security and Protection to all disaster victims in case of crises caused by natural disasters (IOM, 2019a). Despite the government’s endeavours to manage displacements in the country, natural disasters continue to displace people within the country. In Abidjan, in 2020, flash floods triggered by torrential rain displaced 1,560 people (Reliefweb, 2020). In June 2023, heavy rain causing flooding displaced 284 people in Grand-Bassem (IDMC, 2023). In a country like Ivory Coast whose economy strongly depends on agriculture, conflict/violence or disaster that causes displacements directly hurts the livelihoods of people.

Immigration

Immigration

Since 2012, Ivory Coast has enjoyed robust and stable economic growth and remains francophone West Africa’s economic hub (World Bank, 2020). The Ivory Coast migration corridor is one of the top ten in western Africa. Hence, the country is the most favoured destination for migrants in the region. Of the 7.64 million migrants in the region by mid-2020, Ivory Coast was host to 2,564,857 million migrants which constituted 9.7% of the population.

In 2023, the Burkina Faso to Ivory Coast migration corridor had the largest stock of migrants, namely 1,376,350, followed by Mali with 522,146 migrants, and Guinea with 167,516 migrants (Migration Data Portal, 2023).

Like other regions in Africa, migration in this region is driven by economic reasons like business and job prospects in the host country, and economic hardship and poverty in the home country. Other remote factors include educational opportunities and family joining. It could be said that movement within the region is encouraged by the aspiration of regional economic integration. Hence, the free movement of people within the region, the right to residency, and the establishment of the regional organisation ECOWAS all contribute to human mobility.

Female Migration

Female Migration

The search for economic opportunity is one of the main drivers of female international migration in Ivory Coast. In 2010, 46.6% (1,102,789) of the international migrant stock were women. In 2015, the female international migrant stock stood at 46.6% (1,150,088). In 2019, it was estimated to be 46.6% (1,187,881) of the international migrant stock (UN DESA, 2019). Even though as a percentage of the total migration stock into Ivory Coast female migrant stock has been stable from 2010 to 2019, the actual numbers have slightly increased as the number of male migrants increased. Female migration into Ivory Coast, especially from other parts of Africa, is informed by factors such as the search for seasonal jobs and the ongoing political instability characterised by civil wars in the sub-region. Within the sub-region, Ivory Coast is one of four countries (the other countries being Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone) with the lowest number of female migrants as a percentage of the total migration stock (ILO, 2020). However, the percentages of women migrants from Ivory Coast as a stock of the total Ivorian migrant population are higher for migrant girls (54.1%) and young women (69.3%) than for boys and young men (ibid). The conflict in the region has turned some of the women into the sole providers of their households and these women are using migration as a means of survival and providing for their families left behind.

Children

Children

Ivory Coast is one of the top ten countries hosting child migrants in Africa (Migration Data Portal, 2023). According to UNICEF (2019), with a recorded 313,000 child migrants, Ivory Coast was ranked sixth on the log, with the highest number of child migrants on the continent after South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya. One of the key challenges of migrant children in Ivory Coast is access to social services such as school. These challenges are partly linked to the statelessness status of parents of migrant children, which is informed by two key factors: i) the failure to grant nationality to workers recruited from neighbouring countries during the colonial era to work in the plantations, which had a trickle-down effect on their descendants as they also have no nationality, and ii) the absence of a legal framework to give nationality to abandoned children also known as foundlings (UNHCR, 2014-2022). The accompanying curfews and lockdown restrictions during the Covid-19 outbreak have increased the vulnerability of migrant and displaced children in Ivory Coast as most of them depend on the streets to live or work (UNICEF, 2020).

Refugees and Asylum seekers

Refugees and Asylum seekers

Despite its past political tensions and social unrest, Ivory Coast has kept its borders open to those seeking protection. Recently, Ivory Coast has become the point of departure rather than the destination for refugees. In November 2024, there were 2,359 refugees and 66,146 asylum seekers in Ivory Coast (UNHCR, 2024). These refugees came from Liberia (1,152), the Central African Republic (608), other countries (191), the Syrian Arab Republic (164), the Democratic Republic of Congo (124), Congo (75), and Rwanda (45) (UNHCR, 2024). The Ivorian government encourages refugees to integrate locally rather than placing them in camps. However, there are refugee camps like the transit refugee camp in Tabou, which is designated solely for refugees in transit, and the refugee camp in Peacetown in Nicla, near Guiglo.

Emigration

Emigration

Historically, as one of the top producers of cocoa and coffee, Ivory Coast was known for its status as a destination country for migrants in the region. However, the two civil wars (2002 to 2007 and 2010 to 2011) that engulfed the country, compounded by the declining prices of agricultural products in the world market, watered down the economic gains of the country and brought about unprecedented poverty and misery among the people, causing young Ivorians in particular to emigrate. By mid-2020, there were over 1.1 million Ivorian emigrants (Migration Data Portal, 2021b).

These emigrants are both skilled and unskilled. While most skilled emigrants use regular pathways, unskilled emigrants rely heavily on irregular pathways. The top destination countries for skilled or trained Ivorians include Burkina Faso (557,732), Mali (188,250), France (99,031), Ghana (72,728), and Benin (33,996) (Diaspora Engagement Mapping, 2020). As a percentage of the emigrant population, emigrants from Ivory Coast comprised lowly educated (47.6%) and higher educated (30.7%) migrants (Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, 2017). These include medical doctors, nurses, and those involved in the manufacturing, distribution, and services industries. According to IOM (2023), a survey revealed that the three main reasons for emigration are the search for jobs (39.39%), education (24.42%), and family reunification (23.39%). Therefore, although the search for economic opportunities remains one of the key drivers of emigration, some emigrate for other reasons, as indicated above.

Labour Migration

Labour Migration

The valorisation of agricultural land for cocoa production and the demand for foreign labour in Ivory Coast also encouraged migration from Burkina Faso. Most of the Burkinabes migrating to the Ivory Coast were in search of paid work to support their family members back home through remittances (MIDEQ, nd). In 2013, 60% of the immigrant population in Ivory Coast came from Burkina Faso (Traore & Torvikey, 2022). Recently, through its regional framework ECOWAS, by implementing the protocol of the free movement of people within the sub-region, Ivory Coast has facilitated the movement of migrant labour from other parts of Africa, in particular from within the region.

Ordinance No. 2007-604 of 8 November 2007 emphasises that nationals of ECOWAS member states do not need a residence permit to stay in Ivory Coast but fails to elaborate on their access to the labour market. However, the relevant ECOWAS protocol excludes the principle of the labour market test, which logically means that ECOWAS member states are not required to obtain work authorisation to work in Ivory Coast (United Nations, 2015). Although not all immigrants are part of the labour force, in Ivory Coast, 85.5% of the immigrant population do form part of the labour force (ibid). In 1977, the Ministry of Labour and the Ivorisation of Executives introduced legal frameworks to limit the recruitment of non-nationals to the education system and public enterprise (Silue, 2019). By 1997 such measures were strengthened and echoed by the 2015 Labour Code (ibid). These legal frameworks created pathways for the unequal treatment of migrant labourers in the country as they enforced the notion of othering within the labour market.

Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking

According to the US Department of State (2024), Ivory Coast is a Tier 2 country as the government is making significant efforts in some respects but does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking in persons. The Ministry of Solidarity is the lead agency for combatting trafficking in persons while the Ministry of Employment is responsible for combating child labour with the support of the Inter-Ministerial Committee for the Fight against Trafficking, Exploitation, and Child Labour. Overall, the government is making a significant effort to meet the minimum standard.

Ivory Coast is a source, transit, and destination country for victims of human trafficking, specifically forced labour and sex trafficking, and partly also drug trafficking (ibid). In line with the National Strategy and National Plan for Combating Trafficking in Persons, the National Committee against Trafficking of Persons oversees the implementation of these laws (IOM, 2019b). Ivory Coast has concluded formal agreements with countries such as Burkina Faso to combat human and child trafficking.

Despite the commitment through a legal framework to combat human trafficking in Ivory Coast, resources, inspections, remediation, and penalties are inadequate (ibid). According to the US Department of State (2024), the government identified and referred to care facilities 2,292 victims of human trafficking (461 sex trafficking victims, 1,532 labour trafficking victims, and 299 victims for unspecified forms of trafficking), mostly Ivorians and nationals from Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Ghana, and other West African countries. However, an NGO estimated that there were more than 790,000 children aged 5 to 17 exploited on Ivorian cocoa plantations (ibid). The discrepancies between the two figures are huge, highlighting possible gaps in the identification process of victims of human trafficking in the country. The government reported investigating 98 trafficking cases in the current reporting year (2024) and continued 13 investigations from the previous reporting year (2023), prosecuted 109 alleged traffickers, and obtained convictions for 46 traffickers (ibid). The limited support provided by adults to children, and the lack thereof in some instances, makes these children vulnerable to re-victimisation. The government runs shelters for child victims of exploitation in Soubre and refers child trafficking victims to NGOs for long-term care (ibid).

Traffickers exploit Ivorian women and girls in forced labour in domestic service, restaurants, and sex trafficking. Ivorian and Burkinabe boys are also exploited through forced labour in the agricultural and service industries, especially cocoa production (US Department of State, 2023). Victims of human trafficking in Ivory Coast typically come from the rural parts of Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, Benin, Togo, Ghana, Morocco, and China. They are mostly located in Abidjan, northern and central Ivory Coast, and the western mining regions near the gold mines in Tengrela (ibid). Nigerian human trafficking victims typically transit through Ivory Coast en route to exploitation in sex trafficking in Asia, the United Arab Emirates, and North Africa. According to the US Department of State (2022), religious leaders also recruit women and girls for work in the Middle East and Europe. During the reporting year (2024), the government reported initiating 10 investigations and continuing 13 investigations, initiated the prosecution of 25 alleged traffickers (23 for sex trafficking and pimping, one for labour trafficking, and one for an unknown form of trafficking), obtained convictions for 19 traffickers, and upheld four trafficking convictions on appeal (ibid). High unemployment levels, the new Labour Code, and the Ivorisation of the labour market increase the vulnerability of both migrants and nationals to human trafficking.

Remittances

Remittances

According to the World Bank (2022), personal remittances received in Ivory Coast oscillated between $342,435,061 in 2016 and $328,290,412 in 2019 and picked up in 2020 ($329,147,639) and reached its all-time high in 2022 and 2023 ($1.04 billion). Personal remittances received constituted 1.5% of GDP in 2022 and 1.3% in 2023 (ibid). In 2018, the main remittance inflow into Ivory Coast came from France (MicroSave Consulting, 2020). Remittance flow into Ivory Coast is used for various purposes, the main one being household consumption needs. With the decline in income and economic opportunities in times of crisis and uncertainty, remittances play an important role in supplementing household income (Konan, 2019). As one of the top migrant destinations in sub-Saharan Africa, remittance flows from Ivory Coast as much as it flows in. For example, according to Cooper, Esser and Dunn (2018), annual remittance flow from Ivory Coast to other African countries amounted to more than $1.6 billion. Despite the decline in personal remittances since 2011, remittances continue to contribute to the economic growth of the country.

Returns and Returnees

Returns and Returnees

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR, 2021c), there are currently approximately 91,000 Ivorian refugees and asylum seekers around the world. Most of them live in West Africa and Europe, with 33,000 in Liberia and a further 22,000 in Europe. Contributing factors to forced migration from Ivory Coast include the civil wars from 2002 to 2007 and 2011 to 2012, and most recently, the violence linked to the presidential and parliamentary elections. Since 2011, some 290,000 Ivorian refugees living in some parts of West Africa have voluntarily returned to their homeland (ibid). A high-level ministerial regional meeting culminated in the government of Ivory Coast and other countries hosting large numbers of Ivorian refugees signing a joint declaration on 7 September 2021 leading to the cessation of Ivorian refugee status on 30 June 2022. According to the UNHCR (2021d), fundamental and durable changes in Ivory Coast have precipitated the desire for a cessation clause regarding Ivorian refugees to be implemented from June 2022. These changes include the following:

- The creation of the Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission in 2011 and the National Commission of Inquiry to investigate human rights violations during the political crisis

- The adoption of an Amnesty Law in December 2018

- Political dialogue with the opposition, launched in December 2020

- The release of some detained opposition members

- The creation of a Ministry of National Reconciliation in March 2021

The return of high-profile opposition leaders since February 2021, including former president Laurent Gbagbo (UNHCR, 2021c).

A UNHCR survey conducted in the region shows that 60% of remaining Ivorian refugees intend to repatriate, 30% are still undecided, and 10% have chosen to stay in their host countries. The UNHCR assists the returnees with transport and financial support to facilitate their reintegration (ibid). 25% of the more than 6,700 voluntary returnees assisted by IOM between 2017 and 2019 were women (ibid). Challenges for these returnees included psychosocial trauma associated with the journey, stigmatisation, being judged and shamed, and even rejection by family members (especially when the women return with a child) (IOM, 2019b). These challenges compromised their integration process.

The World Food Programme facilitates the reintegration process of returnees, welcoming them with food kits and providing them with cash transfers to meet their immediate food and nutritional needs for three months (WFP, 2020).

International Organisations

International Organisations

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Ivory Coast works in close partnership with the government on projects aimed at strengthening institutional capacities in the areas of immigration and border management, and migrant protection and assistance. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Ivory Coast focuses on humanitarian activities and strengthening protection for refugees, returnees, and stateless people. Other migration-related United Nations agencies in Ivory Coast include the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). UNICEF helps returnees to keep their children in school, and the UNDP, in partnership with the government, pilots projects aimed at attaining the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which include good governance and the fight against poverty. The World Food Programme (WFP) provides school meals to targeted children throughout the school year. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) ran mental health disorder and epilepsy projects and provided a telemedicine service in Ivory Coast up until 2019 when they left the country. MSF returned in 2020 to support the national Covid-19 response team in screening and referring Covid-19 patients.

Bassey, J.R. 2011. An assessment of impact of neglect of history on political stability in African countries: The case of Cote d’Ivoire. African Journal of History and Culture, 6(9):149-163. DOI:10.5897/AJHC11.022

Blion, R. 1996. From Ivory Coast to Italy. Burkina Faso migration patterns and national interest. Studi Emigrazione, 33(121):47-69.

British Broadcasting Cooperation (BBC). 2020. Ivory Coast: Country Profile. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13287216

CIA World Factbook. 2021. Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/cote-divoire/

CIA World Factbook 2025. Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/cote-divoire/

Cooper, B., Esser, A. & Dunn, M. 2018. Remittances in Cote d’Ivoire. Cenfri. Retrieved from: https://cenfri.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Barriers-study-volume-5-Remittances-in-C%C3%B4te-d%E2%80%99Ivoire_November-2018.pdf

Diaspora Engagement Mapping. 2020. Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://diasporafordevelopment.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/CF_Cote-dIvoire-v.2.pdf

Dick, E. & Schraven, B. 2021. Rural-Urban Migration in West Africa: Context, Trends, and Recommendations. In: Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), Policy Brief (February 2021). Retrieved from: https://www.idos-research.de/en/others-publications/article/rural-urban-migration-in-west-africa-contexts-trends-and-recommendations/

European Union (EU). 2018. Many more to come? Migration from and within Africa. Retrieved from: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC110703/africa_policy_report_2018_final_1.pdf

UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2018. Climate-Smart Agriculture in Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/3/ca1322en/CA1322EN.pdf

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2020. Women migrant workers’ labour market situation in West Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@migrant/documents/publication/wcms_751538.pdf

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2023. Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/cote-divoire

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019a. Female migration in Cote d’Ivoire: The journey of the returned migrants. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/c-te-divoire/c-te-divoire-research-brief-female-migration-c-te-divoire-journey-returned

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019b. The Republic of Côte d’Ivoire: Migration Governance Indicators Profile. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-governance-indicators-profile-2019-republic-cote-divoire

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020. Cote d’Ivoire – migration de retour: Lien entre irregularite et renforcement de la vulnerabilite des migrants Ivoiriens en Tunisie, au Maroc et Algerie. Retrieved: https://migration.iom.int/reports/c%C3%B4te-divoire-%E2%80%94-migration-de-retour-lien-entre-irr%C3%A9gularit%C3%A9-et-renforcement-de-la

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2022. Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/countries/cote-divoire

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2023. National study of the labour market in Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/pub2023-003-el-natl-study-labour-market.pdf

Knoema. 2020. Côte d’Ivoire: Poverty headcount ratio at urban poverty line as a share of urban population. Retrieved from: https://knoema.com/atlas/C%C3%B4te-dIvoire/Urban-poverty-rate

Konan, S. 2017. Post electoral crisis and international remittances: Evidence from Cote d’Ivoire. Economics E-Journal, Discussion Paper No. 2017-86. Kiel Institute for the World Economy. Retrieved from: http://www.economics-ejournal.org/economics/discussionpapers/2017-86

Maastricht Graduate School of Governance. 2017. Côte d’Ivoire Migration Profile. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiQuJWhzLXyAhW0QEEAHcy7CZMQFnoECAMQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.merit.unu.edu%2Fpublications%2Fuploads%2F1518183449.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0SsgOmIAa5AoMNIoNVYY3B

MicroSave Consulting. 2020. Demand analysis on remittances in West African Francophone countries: Cote d’Ivoire, Mali, and Senegal. Retrieved from: https://www.microsave.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Demand-analysis-on-remittances-in-West-African-Fracophone.pdf.

Migration for Development & Equality (MIDEQ). nd. Burkina Faso – Cote d’Ivoire migration corridor. Retrieved from: https://www.mideq.org/en/migration-corridors/burkina-faso-cote-divoire/

Migration data portal. 2023. Migration data in Western Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/regional-data-overview/western-africa

Migration Data Portal. 2021. Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/data?m=2&sm49=30

Rabat Process. 2018. Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.rabat-process.org/en/countries/66-cote-d-ivoire

Reliefweb, 2020. Cote D’Ivoire: Floods and landslides. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/disaster/fl-2020-000154-civ

Silue, N. 2019. International migration and labour: Foreign workers in Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://journals.openedition.org/rdctss/1342

The Global Economy. 2021. Ivory Coast: Human flight and brain drain. Retrieved from: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Ivory-Coast/human_flight_brain_drain_index/

Traore, N. & Torvikey, D. 2022. Migrants in the plantation economy in Cote d’Ivoire: A historical perspective. In: Teye, J.K. (eds.), Migration in West Africa. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97322-3_10

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2019. International migration stock 2019: South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp.

UN Development Programme (UNDP). 2020. Human Development Report. Retrieved from: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/CIV

UN-Habitat. 2023. UN-Habitat Cote d’Ivoire: Country profile report 2023. Retrieved from: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/07/cote_divoire_country_brief_en.pdf

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2014-2022. The lost children of Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/ibelong/the-lost-children-of-cote-divoire/

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. Côte d’Ivoire Situation. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/79934

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2021a. UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Situational Emergency Update. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/c-te-divoire/unhcr-c-te-divoire-situational-emergency-update-22-january-2021

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2021b. Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/country/civ

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2021c. UNHCR recommends the cessation of refugee status for Ivorians. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/news/news-releases/unhcr-recommends-cessation-refugee-status-ivorians

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2021d. Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/EN%20UNHCR%20Cote%20d%27Ivoire%20-%20Factsheet%20-%20September%202021.pdf

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/civ

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNICEF). 2019. Data snapshots of migrant and displaced children in Africa. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/data-snapshot-migrant-and-displaced-children-africa-february-2019

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNICEF). 2020. In Cote d’Ivoire, protecting children and young people on the move during Covid-19. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/stories/cote-divoire-protecting-children-and-young-people-move-during-covid-19

United Nations (UN). 2015. A survey on migration policies in West Africa: Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/events/other/workshop/2015/docs/Workshop2015_CotedIvoire_Migration_Fact_Sheet.pdf

US Department of State. 2023. Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/cote-divoire/#:~:text=Traffickers%20exploit%20Ivoirian%20women%20and,in%20agriculture%2C%20especially%20cocoa%20production

US Department of State. 2022. Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/cote-divoire__trashed/

US Department of State. 2024. Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/cote-divoire/

UN World Food Programme (UN WFP). 2020. Cote d’Ivoire: “We represent the first phase of Ivorian returnees’ new lives”. Retrieved from: https://medium.com/world-food-programme-insight/c%C3%B4te-divoire-we-are-the-first-phase-of-ivoreans-returnees-new-lives-28e300d645e1

World Bank. 2020. Population total – Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=CI

World Bank. 2021a. Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/cotedivoire/overview

World Bank. 2021b. Côte d’Ivoire: Personal remittances, received (% of GDP). Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=CI

World Bank. 2022. Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Cote d’Ivoire. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=CI