Historical Background

Historical Background

Chad lies in the heart of Central Africa. It is one of the largest countries in the central African region and it has one of the largest land borders in Africa (5,968 kilometres). The country has been an attraction for migrants for centuries, creating a rich tapestry of migration. One of the historical and most common patterns of migration practised over centuries has been the nomadic transhumance movement (International Organization of Migration (IOM), 2022). In the past, this kind of movement allowed herdsmen to develop alliances and exchanges with the sedentary population (Ibid). More recently, the climatic and environmental changes that are adversely affecting the country and are limiting access to resources such as water and farmland are creating growing tension between farmers and herdsmen (Ibid).

Today, the migration patterns in Chad have become highly diverse and complex. The centrality of the country on the continent and its proximity to Libya makes it both a host, transit and return country for migrants. The political crisis in the central region has found expression in different forms with all six neighbouring countries to Chad positioning Chad as a host country of refugees. However, Chad’s political and economic woes have forced many Chadians to seek refuge in other African countries. Still, because of the conflict within these countries, many Chadians are obliged to return to Chad. Furthermore, Chad is a transit country for some migrants who wish to go to Europe via Libya and the Mediterranean Sea.

Migration Policies

Migration Policies

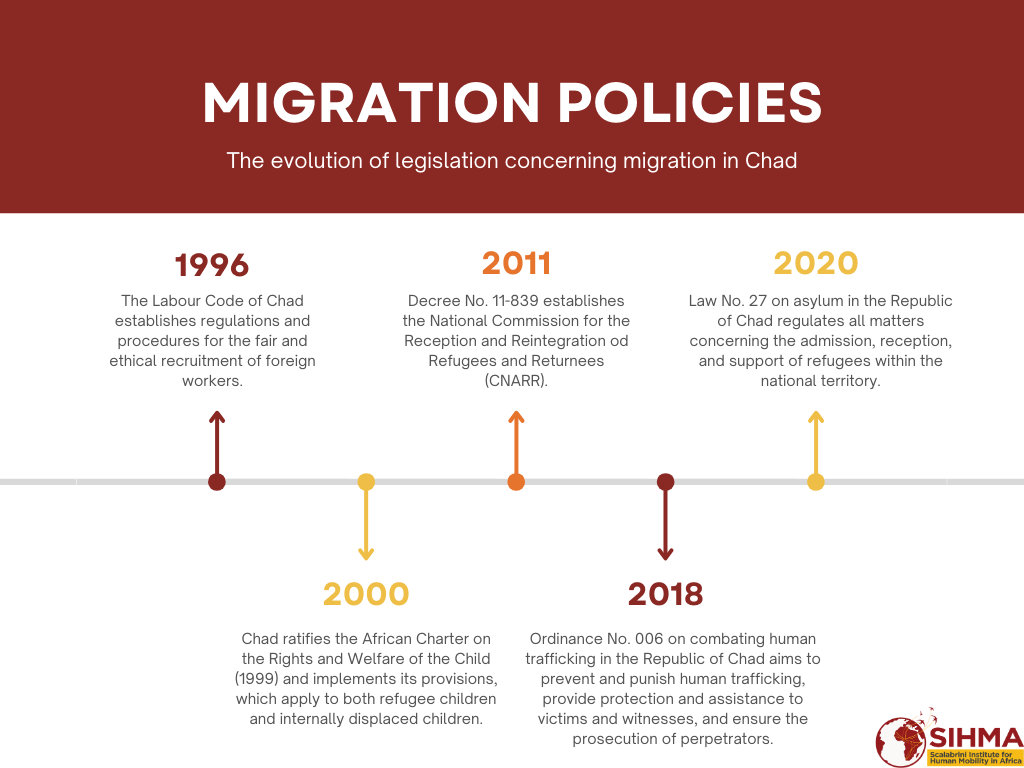

Chad has different legal frameworks for migration management. At domestic level, for regular immigration, Chad has regulations related to the entry, stay, and permanence of foreigners. In a move to enhance the protection and improve the living conditions of migrants and refugees in the country, Chad, in line with the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants in 2018, acceded to the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugee (UNHCR), 2018). On 2 August 2011, Decree No. 11-839/PR/PM/MAT/11 provided for the establishment, organisation, and powers of the National Commission for the Reception and Reintegration of Refugees and Returnees (CNARR) (Rabat Process, 2018). The constitution of 31st of March 1996, revised on 15 July 2005, and amended in 2018, in Article 15, prescribes equal treatment for nationals and non-nationals (University of Nottingham, 2021).

Timeline of Migration Policies in Chad. Source: SIHMA

At regional level, the relevant regulations for regular immigration and emigration are those contemplated upon by the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), with free movement of people as one of their key objectives. Even though the ECCAS passport is not effective, it is important to note that six member states of CEMAC (Gabon, Cameroon, Chad, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo, and Equatorial Guinea) within ECCAS have instituted a common passport between them, doing away with visa procedures or restrictions between nationals of the six countries (African Union, 2019). Chad has also ratified the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. In addition, Chad is a signatory to the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa. Beyond the continent, Chad is a signatory to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol.

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

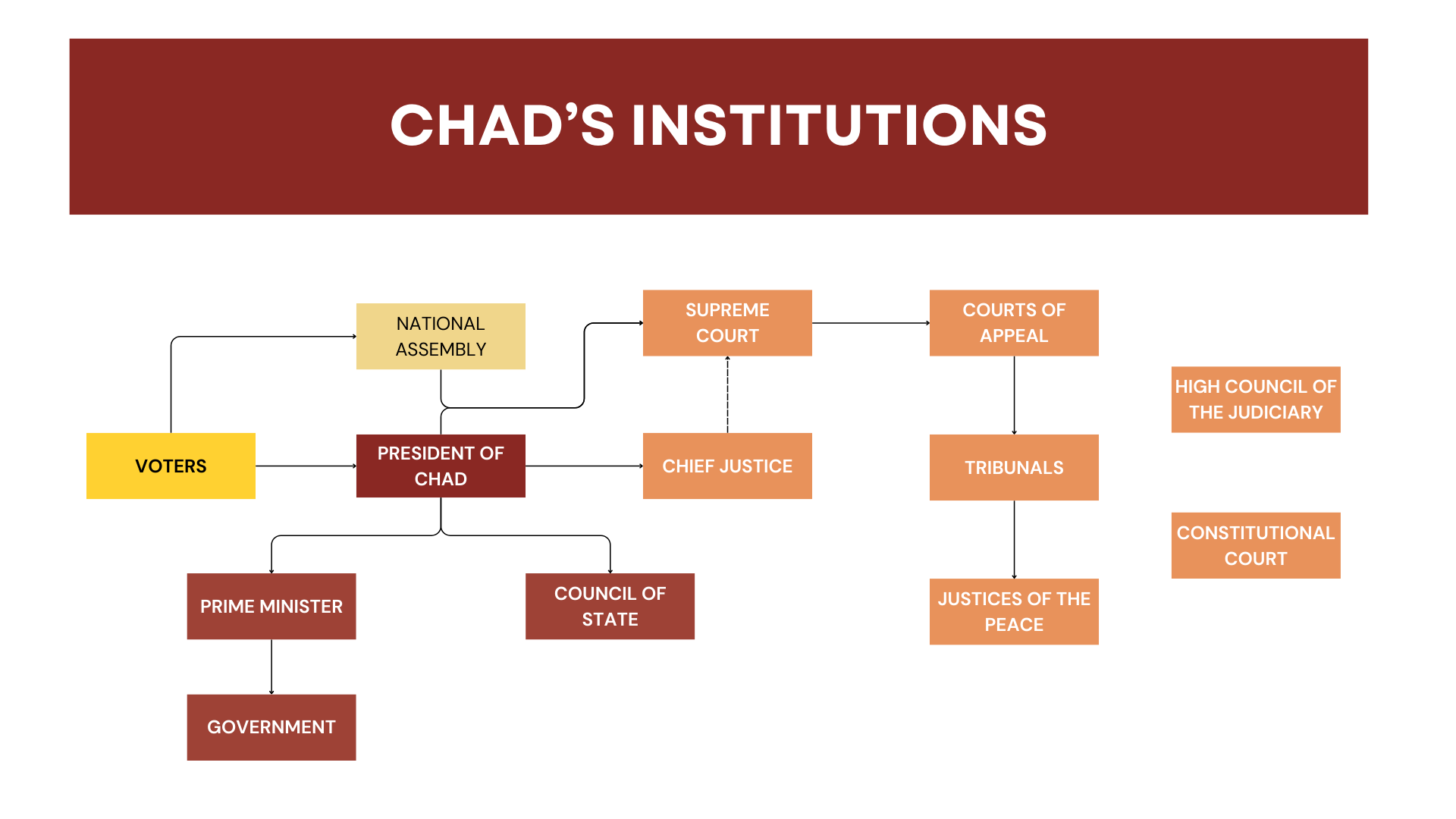

The main ministries in charge of migration affairs in Chad are the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, African Integration, International Cooperation and the Diaspora, which deals with international cooperation issues and oversees relations with the Chadian diaspora, and the Ministry of Territorial Administration, Public Security, and Local Governance, which coordinates the work of CNARR which is in charge of civil status issues (Rabat Process, 2018).

Chad's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

Internal migration in Chad is influenced by economic, social, and cultural factors. Economic attraction remains one of the key drivers of internal migration in the country. Notable economic attraction areas include the gold mines in northern Chad, the agricultural areas in the south, and the fishing areas in the Lake Batha and Salamat provinces (IOM, 2022). Other social and cultural factors that precipitate internal movement include business trips, and the movement of migrants re-joining family members for festivities (Ramadan and Christmas) (IOM, 2019).

Essentially, the three provinces of Borkou, Tibesti, and Moyen-Chari have high volumes of migrants. The provinces of Ouaddai, Batha and Ennedi Ouest have medium and low volumes of migrants living in them respectively (Ibid). Various nomadic groups in Chad migrate nationally and beyond the borders in search of fodder for their livestock. This movement occasionally creates conflict between sedentary farmers and pastoral grazers over resources – particularly in Mayon-Chari, a province in Southern Chad (IOM, 2019; IOM, 2022). The search for livelihood opportunities and the desire for family reunions are essential elements that shape the internal migration pattern in Chad.

Internally Displaced Persons

Internally Displaced Persons

Factors such as conflict, climate change, food insecurity, hunger, and poverty account for internal displacements in Chad. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) (2022), by the end of 2021, an estimated 392,000 people were displaced due to conflict and violence, and 24,000 as a result of disaster. The data indicates that conflict and violence remain the key drivers of internal displacement in Chad.

The conflict that affects people in the country is impacted by internal and external forces. Central African Republic (CAR) accuses Chad of supporting rebel groups that want to destabilise the country, which led to armed clashes between troops from Chad and CAR near the Lagone border post, triggering the displacement of an estimated 4,900 people (IDMC, 2022; The Defense Post, 2021). Also, within Chad, intercommunal conflict – caused by factors such as limited transhumance corridors and competition for resources like water, pasture, and farmland – has contributed to violence-related internal displacement in Chad (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 2024). For example, in 2023 an estimated 2,700 people were displaced because of intercommunal violence in the Southern and Lac regions (Ibid). Furthermore, disaster-induced displacement is predominantly caused by flooding. For example, the IOM (2024) indicated that flooding accounts for the internal displacement of more than 13,000 people with nearly half of them (5,137) located in N’Djamena (Ibid). In a country with a poverty rate of 44.8% (World Bank, 2024) and heavily dependent on the agricultural sector for livelihoods, any form of displacement only increases the economic precarity of the people in that country.

Immigration

Immigration

Despite Chad’s economic status and an uncertain political climate, the economic potential of its gold mines and other opportunities and its positionality in the central African region continue to attract migrants to the country. According to UN DESA (2020), as reported by the Migration Data Portal (2021), the number of immigrants in Chad is steadily increasing. The report indicated that in 2010, there were 417,000 immigrants in the country, growing to 467,000 in 2015 and to 547,500 in 2020 (Ibid).

Also, because of its centrality in the region and its proximity to Libya, which is considered a gateway to Europe from Africa via the sea through irregular migration channels, Chad is considered as a transit country for most migrants who are attempting to reach Europe via the Mediterranean Sea. Recently, several migration routes have been established by migrants predominantly from Cameroon, South Sudan, and Central African Republic as transit routes. These routes include Kalait in eastern and northern Chad, Faya in northern Chad, and Zouarke further north (Tubiana, 2018). Chad therefore represents not only an economic destination but also a transit country for migrants within the region who plan to go to Europe.

Female Migration

Female Migration

The migration dynamics in Africa are seeing more women migrating. However, statistics on international female migrants in Chad are limited. Yet, according to statistics collected by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2020) from three flow monitoring points in Chad, factors such as the need to join other family members and to independently search for economic opportunities account for the flow of female migration into Chad. This limited information aligns with the general pattern of migration on the continent that sees more women independently migrating in search of economic opportunities to take care of their families.

Children

Children

All six of Chad’s neighbouring countries have experienced or are experiencing a form of conflict. These conflicts often adversely affect children and, in some cases, force them to move. For example, since the outbreak of the war in the Darfur region in Sudan, at least 700 unaccompanied migrant children in the Irdimi camp in Chad were assisted by an organisation called Hayat offering them care and support until November 2023 (Radio Dabanga, 2024). The absence of support from organisations usually providing support and care to this group of vulnerable migrants increases their vulnerabilities and exposes them to economic hardship and human trafficking. For example, according to Radio Dabang (2024), there were five cases of child deaths because of starvation in the Irdimi camp.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Various conflicts in neighbouring countries have resulted in more people moving into Chad. Refugees in Chad mostly live in the 13 refugee camps and one site (Amn Nabak, Breidjina, Djabal, Farchana, Gaga, Goz Amir, Iridimi, Kouchaguine-Moura, Kounougou, Mile, Oure Cassoni, Touloum, Treguine, and Kerfi). As of April 2025, there are an estimated 1,357,776 refugees and asylum seekers in Chad (UNHCR, 2025). The refugees in Chad are from the following countries: Sudan (1,184,842), Central African Republic (141,487), Nigeria (21,430), Cameroon (8,619), Various (1,185), and the democratic Republic of Congo (213) (ibid).

The presence of refugees in Chad from countries like Sudan and the Central African Republic is largely informed by the recurrent political instability within these countries, and those from Nigeria are informed by the Boko Haram insurgency in the northern province of the country. In a country plagued with political, economic, and social challenges, hosting refugees is a daunting task, as the country has limited resources to meet the basic needs and facilitate durable solutions for refugees. However, the country has made progress in addressing some of the key challenges of refugees. For example, the country’s commitment to the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework and the Global Compact on Refugees has facilitated and fast-tracked the process of social cohesion within communities by integrating 65% of refugees from the camps into the host communities, integrating refugee schools into the National Educational System, and integrating refugees into the National Health System. With its limited resources, Chad is committed to welcoming, protecting, and integrating refugees within its communities.

Emigration

Emigration

Although Chad is one of the African countries subjected to conflict and violence within the region, the search for economic opportunities remains a key driver of emigration from Chad. The emigration pattern of Chadians indicates that most international migrants from Chad migrate to other African countries, mostly neighbouring countries. For example, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2022), of the estimated 222,303 international migrants from Chad, the majority of them went to Sudan (103,065), Nigeria (31,261), Cameroon (27,852), Central African Republic (10,608), Niger (1,459), and Libya (918) – while in Europe the estimated emigration stock stood as follows: Italy (739), Malta (467), Spain (180), and Greece (71). However, it is important to note that the figures might differ depending on the source. For example, while UN DESA, which draws its information from country census data, indicates that there are less than 1,000 Chadians in Libya, the Displacing Tracking Matrix (DTM) estimates that there are about 82,180 Chadians in Libya (IOM, 2022). The political instability in neighbouring countries including Chad and Sudan undoubtedly had a spillover effect on Chad, which has adversely affected the country's economic outlook, forcing Chadians to emigrate in search of economic opportunities.

Labour Migration

Labour Migration

Labour migration flow in Chad is dynamic and multifaceted as it involves both Chadians and non-Chadians searching for opportunities. With limited economic opportunities in the formal sector, most migrant workers are involved in the informal sector. One of the areas of attraction of migrant labour in Chad is the gold mines. For example, the gold mining areas in the Tibesti region, precisely in the areas of Miski and Kouri Bougi, have attracted migrant workers not only from Chad but also from west and central Africa who are mostly involved in illicit mining (IOM, 2018). Some of the labour migrants in Chad are transit migrants who first need to replenish their resources before moving on (Ibid).

Because of the precarious nature of jobs in this sector, migrants, both nationals and non-nationals, are often victims of exploitation, human trafficking, and abuse (IOM, 2023a). Although the government is implementing labour practices that protect the rights of migrant labourers (see Article 71 of the 1996 Labour Code, for example) (IOM, 2023b), there is a need for the government to strengthen labour migration governance within the informal economy where there is a strong presence of migrant labourers in order to protect the rights of these vulnerable groups of people.

Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking

The government of Chad does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of human trafficking, but it is making significant efforts to do so (US Department of State, 2024). Chad is considered a Tier 2 country owing to increased efforts demonstrated by government officials in this regard. This includes obtaining two successful convictions in the past three years, training judicial and law enforcement officials, prosecuting more suspected traffickers, and identifying more victims (Ibid). Despite being a landlocked country, Chads is still a departure, transit, and destination point for victims of human trafficking and migrant smuggling. During the reporting year (2024), the government reported prosecuting two suspected traffickers and obtaining convictions for two traffickers (Ibid). The prosecuting and conviction rates are low because the government departments (judges, prosecutors, police, and gendarmerie) involved with human trafficking are under-resourced (Ibid).

Human trafficking in Chad is predominantly internal although international human trafficking have been reported, mostly affecting women and children. Internal trafficking mostly involves parents entrusting children to relatives in return for promises of education, apprenticeship, goods, or money (Ibid). In some cases, women and children will be forced into involuntary domestic servitude or involuntary herding (shepherd children). Some of these children are forced to beg in urban areas (commonly known in Chad as Mahadjirine) or work as agricultural labours on farms or in gold mines, and there are cases of sexual exploitation that remain barely documented (Ibid). Illicit networks of traffickers may force adult and child refugees, as well as internally displaced persons in Chad, to take part in commercial sex as their population is vulnerable to trafficking because of their financial situation and lack of access to a support system (Ibid). Victims of human trafficking in Chad receive minimal support from the government as the government does not provide or support services that civil society organisations offer to victims of human trafficking. The under-resourced nature of those involved in the management of human trafficking in Chad implies that the scourge of human trafficking is underreported, making it a “lucrative business” for traffickers who go unabated.

Remittances

Remittances

In a country with a poverty incidence of 44.8% and with an estimated 7.8 million people experiencing poverty – primarily in rural areas where one in two people is considered poor – migration and remittances remain a viable solution to provide financial assistance to households and support economic development in Chad (IOM, 2024a; World Bank, 2024). There are no current statistics on the volume of the flow of remittances in Chad as the most recent World Bank data dates back to 1994. Yet, the World Bank in its overview of the entire sub-Saharan region including Chad indicates that remittance flow would have increased by 1.9% (IOM, 2020; World Bank, 2023). In addition to the economic dimension of remittances and its immediate impact on improving household consumption and realising the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in reducing poverty, increasing access to food and education, driving financial inclusion, and reducing inequalities, Chad also benefits enormously from social remittances through the flow of ideas, knowledge, and skills from the diaspora. For example, the Chadian diaspora came together and created a self-help group called "Groupe d’entraide a l'Enseignment Supérieur" of nearly 200 Chadian experts (medical doctors, researchers, and engineers) to help improve the health sector of the country (IOM, 2020). Remittances therefore constitute both an economic and social lifeline to most Chadians, particularly those living in rural areas where the propensity of poverty is very high compared to those living in urban areas.

Return and Returnees

Return and Returnees

Intra-African migration is a prevalent migratory pattern on the continent with migrants moving into neighbouring countries in particular. Currently, the political situation in the central African region is fragile with most Chadian neighbouring countries experiencing various forms of political instability. Return migration is, therefore, an eminent component of the migration pattern in Chad. For example, since the onset of the crisis in Sudan, an estimated 209,153 Chadians have returned home to Chad. Also, inter-community clashes in the Far North provinces of Cameroon have seen an estimated 750 Chadians returning home (IOM, 2022; IOM, 2024b).

Returnees are supported with medical assistance, psychosocial assistance, entrepreneurship training, and social assistance to facilitate their integration process within their host communities (IOM, 2024c). Political instability and economic hardship in host countries remain key drivers of return migration in Chad.

International Organisations

International Organisations

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) maintains a strong presence in Chad. For example, the IOM in collaboration with local partners and the government of Chad engage with diaspora, help to stabilise communities, provide humanitarian assistance, provide durable solutions for migrants and displaced populations, develop migration policies, support immigration and border management, support peacebuilding and mediation efforts, gather migration data and undertake research, provide counter-trafficking programmes, and help with transhumance management. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), through the development of project implementation teams, assists refugees, asylum seekers and community members with education, health, food security and nutrition, and protection through the Emergency Food and Livestock Crisis Response Project in order to increase social cohesion, peaceful cohabitation and intercommunity dialogue between refugees, returnees, and host communities.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), International Rescue Committee (IRC), and the World Food Programme support and protect children, especially those displaced, uprooted or trapped in violence, with food, basic services, and education. Oxfam, which aims to find long-term solutions for displaced populations, is helping displaced people with potable water, and cash to cover their most basic needs. Oxfam also helps them to obtain birth certificates. Mercy Corps provides food aid to vulnerable populations (including refugees) and was involved in sensitising the IDPs in Chad on the importance of participating in the 2019 general elections through voter education. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) provides access to health care in refugee camps and supports health clinics in several small villages.

African Union. 2019. Towards an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa: Voices of the RECs. Retrieved from: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/38176-doc-african_integration_report-eng_final.pdf

Global Compact on Refugees. 2024. Chad. Retrieved from: https://globalcompactrefugees.org/gcr-action/countries/chad

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2022. Country profile: Chad. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/chad/

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2018. IOM Chad calls for urgent funding to assist thousands of migrant gold miners. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/news/iom-chad-calls-urgent-funding-assist-thousands-migrant-gold-miners

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. Mobility in Chad: Mapping of mobility trends and flows in Chad. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/map/chad/mobility-chad-mapping-mobility-trends-and-flows-chad-august-2019

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020. Understanding remittances behaviour in Chad amid COVID-19: IOM launches first study on remittances. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/news/coronavirus/understanding-remittances-behaviour-chad-amid-covid-19-iom-launches-first-study-remittances

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020. Women on the move in Northern Chad. Retrieved from: https://dtm.iom.int/dtm_download_track/10021?file=1&type=node&id=7863

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2022. 8 facts to know about migration in Chad. Retrieved from: https://rodakar.iom.int/stories/8-facts-know-about-migration-chad

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2022. Germany supports IOM emergency response to assist Chadian returnees from Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/news/repatriation-chadian-migrants-who-fled-central-african-republic-car-and-are-stranded-cameroon-23-july-21-august-2014

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2022. Mapping mobility in Chad. Retrieved from: https://chad.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl2471/files/documents/2023-11/mapping-mobility-in-chad-june-2022.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2022. Mobility mapping in Chad. Retrieved from: https://dtm.iom.int/reports/chad-mobility-mapping-chad-june-2022

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2023a. Strengthening labour migration governance in Chad. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/project/strengthening-labour-migration-governance-chad

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2023b. Migration governance indicators. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/overviews/mgi/chad

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2024. Five things to know about remittances in Chad. Retrieved from: https://rodakar.iom.int/stories/five-things-know-about-remittances-chad

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2024b. IOM Chad: Sudan crisis response. Update No. 46. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/chad/iom-chad-sudan-crisis-response-situation-update-no-46-21-november-2024

Migration Data Portal. 2021. Chad. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA). 2024. Chad: Overview of inter/intra-community conflicts (July 2024). Retrieved from: https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/chad/chad-overview-interintra-community-conflicts-july-2024

Rabat Process. 2018. Chad. Retrieved from: https://www.rabat-process.org/en/countries/chad

Radio Dabanga. 2024. Hundreds of unaccompanied Sudanese children in Chad camps. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/chad/hundreds-unaccompanied-sudanese-children-chad-camps

The Defense Post. 2021. Chad sends more troops to CAR border. Retrieved from: https://thedefensepost.com/2021/06/04/chad-troops-car-border/

Tubiana, J., Warin, C. & Saeneen, M. 2018. Report: Multilateral damage: The impact of EU migration policies on central Saharan routes (Chapter 4: Chad, a new hub for migrants and smugglers?). Retrieved from: https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2018/multilateral-damage/4-chad-a-new-hub-for-migrants-and-smugglers/

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2018. UNHCR welcome the accession of the government of Chad to the Comprehensive Refugee Framework. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/chad/unhcr-welcomes-accession-government-chad-comprehensive-refugee-response-framework

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Chad. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/tcd

University of Nottingham. 2021. Chad 2018. Retrieved from: https://cjad.nottingham.ac.uk/documents/implementations/pdf/Chad-Constitution_2018_EN.pdf

World Bank. 2024. Chad: Overview. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/chad/overview