Historical Background

Due to its political stability after independence and its strategic geographical position, Cameroon has been the destination country for many migrant people, especially during the 1970s. Between 1970 and 1980, Cameroon registered an upward immigration trend, recording 143,611 immigrants in 1976 and 257,689 in 1987, mostly labour immigrants from neighbouring countries like Nigeria, Chad, Guinea, and the Central African Republic (Ache, 2016). However, Cameroon started to experience an economic meltdown with the economic crisis in 1980. The situation worsened when the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund introduced the Structural Adjustment Programme in 1988. In a country where the government is the main employer of labour, the economic requirements of the Structural Adjustment Programme, which pushed for the downsizing of the state, resulted in the freezing of employment opportunities and the devaluation of the currency, making living conditions in Cameroon increasingly difficult for its inhabitants. Recently, the two Anglophone regions have turned the Anglophone Crisis, which started in 2016, into an expression of dissatisfaction with their under-representation in and cultural marginalisation by the central government. This is undermining the already precarious state.

Cameroon is known for its cultural diversity and resource endowment. Yet, the country’s Human Development Index (HDI) 2021-2022 stood at 0.576 and the country is ranked 151 out of 191 countries (United Nations Development Programme, 2023), with 37.5% of Cameroonians living below the poverty line (World Factbook – CIA, 2022). Cameroon has a stagnant per capita income, a relatively inequitable distribution of income, a top-heavy civil service, endemic corruption, and a generally unfavourable climate for business enterprise (ibid). According to criteria adopted by Transparency International in 2020 (Corruption Perception Index), Cameroon featured among the 38 most corrupt countries in the world (Transparency International, 2022).

The country’s bleak socioeconomic and political situation has led to the loss of a significant percentage of the economically active population, especially the mobile youth. This is resulting in a brain drain as growing numbers of experts travel abroad in the hope of crafting a better future for themselves and their families. Many of those who leave support their extended families in Cameroon through remittances, which has become an important factor in the country’s economy. Paradoxically, Cameroon is considered a “safe haven” for many fleeing from the war in the Central African Republic and the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria. Yet, to some Cameroonians, especially those from the two Anglophone regions experiencing political tension between pro-independence fighters and government forces, the country is at war.

Migration Policies

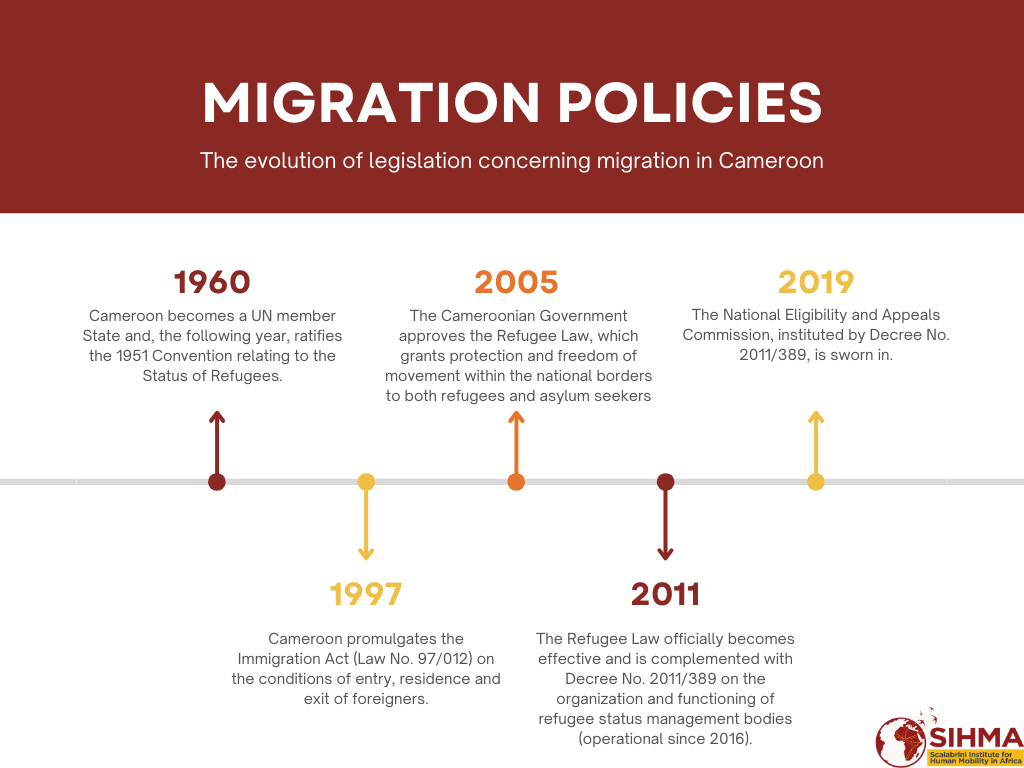

Since becoming a UN member state in 1960, Cameroon has signed and ratified various international laws pertaining to refugees and asylum seekers. However, it was only in 1997 that the government promulgated the Immigration Act (No. 97/012, 10/01/1997), outlining the terms and conditions for the entry, security, transfer of funds, and return policies of foreigners. Cameroon supports the mobilisation of diaspora practices and co-development projects, which are aimed at the return of Cameroonian skilled professionals who migrated to Europe. The Refugee Law was signed in 2005 and became effective six years later, granting protection and freedom of movement within the national borders to both refugees and asylum seekers (requiring the latter to inform the authorities whenever they are changing their addresses). In Cameroon, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) deals with claims of asylum seekers and decides on their status as refugees. Denied applicants are allowed to appeal to the UNHCR office, but courts cannot review decisions.

Timeline of Migration Policies in Cameroon. Source: SIHMA

According to the Refugee Law, refugees have the right to work, own or transfer property, and be employed in almost all job fields (except in parastatal and civil service occupations). However, any contract of employment involving a foreigner must first be submitted to and approved by the Ministry of Labour. Many migrants have no alternative to informal work and set tasks.

The same law grants refugees protection in labour, access to medical health care (at the same conditions as nationals), and the right to education through scholarships provided by the government or funded by NGOs.

Governmental Institutions

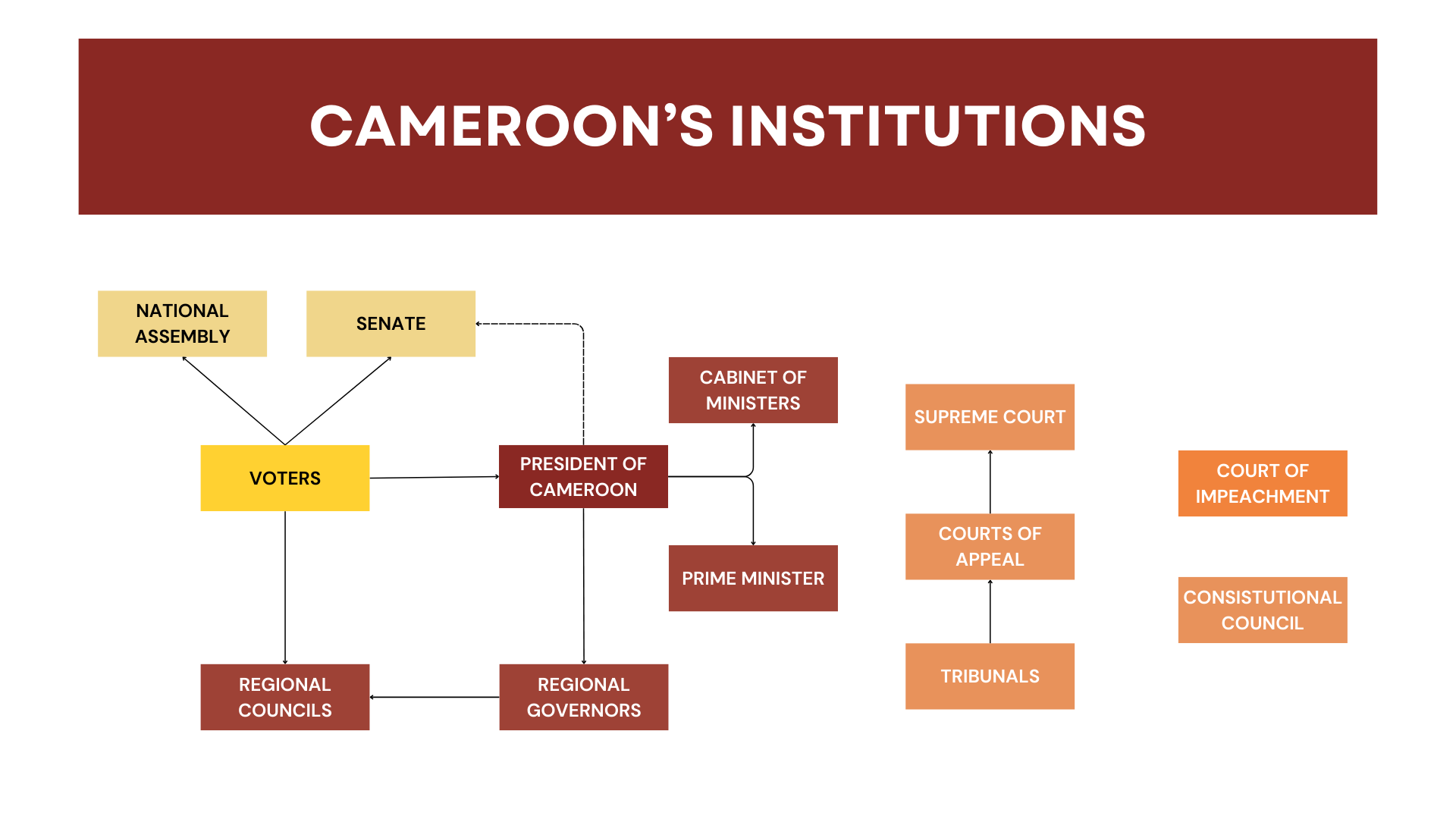

Three ministries oversee migration affairs in Cameroon:

-

The General Delegation of National Security oversees emigration, immigration, and border management.

-

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the focal point for international cooperation on migration issues. It oversees relations with the Cameroonian diaspora and handles requests for legalisation from foreign associations present in Cameroon.

-

The Prime Minister’s Office oversees the Interministerial Technical Platform for the Management of Labour Migration (Rabat Process, 2018).

Cameroon's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

Internal Migration

There is a lack of reliable data on internal migration in Cameroon. However, current trends indicate that because of the pull factors of better opportunities in the cities, Cameroon has one of the highest rates of urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa, with 56% of the population living in urban areas (World Bank, 2018).

Within the context of Cameroon, two types of internal migration are common: intraregional and interregional migration. Yaoundé and Douala, with their major urban conglomerates, are net receivers of intraregional internal migrants. According to Mberu and Pongou (2012), the internal migration index in Cameroon was estimated at 32.5%, making the country one of the highest in the region with an internal migration population. The extreme North, West, and North-West are the three regions with the highest number of internal migrants (ibid). The majority (26.2%) of internal migrants come from the Western region (ACP Observatory on Migration, 2013).

Unequal development and poverty in rural areas compared to urban areas are the main drivers of internal migration in Cameroon, as the majority (90%) of those who migrate are youths below the age of 35 in search of better opportunities (Mberu & Pongou, 2012). With the imbalance of rural versus urban development rates, it is estimated by the United Nations that, by 2050, 70% of Cameroon’s population will live in urban areas (World Bank, 2018). Douala has the strongest competitive edge (in terms of the concentration of industries) with employment in 31 different industries. This can be compared to cities like Yaounde, Bafousam, Ngaoundere, Maroua, Bamenda, and Kumba, which offer the competitive edge of employment in seven to 13 different industries (ibid). It is argued that, within Cameroon, internal migration improves the living conditions of migrants, leading to the emergence of an informal economy sector, which is a source of job opportunities, thus dominating the national economy of Cameroon.

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), Conflict and Disasters

In May 2022, there were over 1.1 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Cameroon because of conflict/violence and disaster, making it the second largest host country of IDPs in the region (IDMC, 2022). The challenges confronting IDPs in Cameroon include access to education, nutrition, and accommodation. Some of the IDPs live in camps while others are settled in communities that have shown hospitality and solidarity (Fomekong, 2021).

2,120,560 Internally Displaced Persons in Cameroon (2024)

Conflict and violence are the main drivers of internal displacement in Cameroon. As a result of the Boko Haram insurgency in the Far North region and the current Anglophone Crisis in the North West and South West regions of Cameroon, there is a growing number of conflict-related displacements in the country, except for in 2021, when there was a slight decrease, as shown in the graph below.

Conflict and violence are the main drivers of internal displacement in Cameroon. As a result of the Boko Haram insurgency in the Far North region and the current Anglophone Crisis in the North West and South West regions of Cameroon, there is a growing number of conflict-related displacements in the country, except for in 2021, when there was a slight decrease, as shown in the graph below. A peak in displacement occurred during 2020, with a slight decrease in the following year.

Natural disasters like landslides and floods also contribute to internal displacement in Cameroon. For example, landslides in Kupe-muanenguba and Nguti in the South-West region displaced 21,200 people in 2020, while floods displaced 4,400 people in Douala in 2020 and 1,800 people in the Far North region in 2021 (ibid).

Although the main driver of internal displacement in Cameroon is associated with the current crisis in the North-West and South-West regions, as indicated earlier, things are gradually returning to normal and the numbers of those displaced are steadily declining.

Immigration

Cameroon, commonly referred to as “Africa in miniature” due to its cultural diversity and resource endowment (wood, cotton, refined petroleum oils, unwrought aluminium, etc.), remains an attractive destination for immigrants worldwide and within the region. According to UN DESA (2025), Cameroon has experienced a steady increase in its international migration flow from 2010 to 2024. In 2010, the stock of international migrants in Cameroon was 990,500 (1.5% of the total population).

In 2015, it stood at 1.2 million (2.2% of the total population) (ibid). In 2020, it went up to 1.3 million and 1.4 million in 2024 (2.2% of the total population) (ibid). The top five countries of immigrants in Cameroon are the Central African Republic, Nigeria, Chad, Niger, and Mali. The composition of the top five countries of origin for the immigrant population highlights the nature of intra-African migration within the continent. Although Cameroon is plagued with armed conflict crises in the Far North, North-West, and South-West regions, it remains an attractive destination for immigrants from other parts of the world.

Gender/Female Migration

There is a paucity of information on female immigrants in Cameroon. According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2020), of the 579,200 immigrants in Cameroon by mid-2020, 50.6% were female. Most of the female migrant population group in Cameroon are circular migrants, mostly from neighbouring countries like Nigeria, who are involved in cross-border trading. However, in attempting to conduct their small-scale informal businesses in the country, these migrant women are subjected to challenges like stigmatisation, violence, and harassment. In response, the government assists migrant women in Cameroon with valuable information and services that support their businesses (UN Women, 2010).

Minors

According to UN DESA (2020), as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), of the 579,200 immigrants in Cameroon by mid-2020, 39.6% were children. Most of the child migrants in Cameroon are victims of the protracted political instability in the Central African Republic (CAR) and the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria, which have seen thousands of child migrants, some of them unaccompanied, moving into Cameroon, particularly in the Far North Province of the country. These child migrants face challenges such as access to education, nutrition, and accommodation. The absence of these essential services has prompted humanitarian organisations to step in and assist these vulnerable children. For example, UNICEF provided interim and follow-up care to 1,143 and 527 unaccompanied and separated children from Nigeria and CAR, respectively (UNICEF, 2017). The long-standing and persistent nature of the crises in neighbouring countries such as the CAR and Nigeria gives rise to a constant flow of child migrants, some unaccompanied, from these countries seeking better living conditions and educational opportunities in Cameroon.

The ongoing Anglophone armed conflict, also known as the Anglophone Crisis or Cameroonian Civil War, in the North-West and South-West regions of Cameroon has led to the closure of several schools. For example, in 2022, two in every three schools were closed in the affected regions, compounding the already precarious situation of child migration in the country (International Crisis Group, 2022). According to UNICEF (2019), of the 855,000 children left out of school because of the armed conflict in the regions, 150,000 are displaced.

From a legal point of view, Cameroon has thus far signed and ratified the most important international laws and protocols regarding children’s rights: the 1990 Child Rights Convention and the 2004 UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children. In 2011, the government also promulgated a national law against child trafficking (024/2011). As far as migrant children are concerned, the Immigration Act (006/2005) gives any refugee’s child the status of refugee, favours family reunification and, in the case of unaccompanied children, grants them the status of refugees. According to Cameroonian law, children have the right to education, health care, and naturalisation and must be protected from child marriages as well as any form of exploitation.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Cameroon has a long history of providing refuge to asylum seekers and refugees in the Central African Region. In principle, Cameroon is a conducive host for refugees. Cameroon is ranked 7th in Africa and 13th in the world among the largest host countries (World Bank, 2018). According to the UNHCR (2025), as of March 2025, Cameroon was host to 413,764 refugees and asylum seekers. More than half of the refugees and asylum seekers (284,170) are from the Central African Republic, 126,171 come from Nigeria, and the rest are from Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Rwanda, the Republic of Congo, Burundi, and Côte d’Ivoire (ibid). The refugees from CAR are predominantly located in the Eastern region of Cameroon, while those from Nigeria are predominantly located in the Far North region of the country (UNHCR, 2023b). The majority of the Nigerian refugees in the Far North are victims of the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria, while the refugees in the Eastern region are victims of the political and sectarian violence that has engulfed the Central African Republic since 2013. While a substantial number of refugees live within the border regions of their host communities, some live in refugee camps like Lolo, Gado-Badzere, Ngam, and Minawao, and some in urban cities like Yaoundé and Douala (UNHCR, 2020). Refugees living in the camps are provided with psychosocial support and business training for self-sustenance.

Cameroon is considered a refugee conducive country. Yet, the repressive nature of the state against dissenting voices, despite the constitutional imperative that guarantees freedom of speech and association, makes the country a refugee origin country as well. (In this regard, see Article 19 of the Cameroon Constitution and the US Department of State’s 2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Cameroon).

Emigration

The adverse effects of the economic crisis of 1980 to 2000, the implementation of the Structural Adjustment Programme by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the devaluation of the Cameroonian currency (Francs CFA) made emigration in search of economic opportunities (greener pastures) an attractive venture for many Cameroonians. In the Anglophone regions of Cameroon, the movement is commonly referred to as “bushfalling” which metaphorically means someone who goes into the bush or forest to hunt and bring home food. In the French regions, it is commonly referred to as “aller en adventure a mbeng” which loosely translated means to go for adventure to the North (Nyamnjoh, 2011). The perception, dreams, hopes, and aspirations of a better life abroad remain one of the key drivers of emigration from Cameroon.

In 2013, the United Nations recorded a total of 251,527 emigrants from Cameroon who were residing in France (78,561), the United States of America (48,952), Gabon (48,255), Nigeria (48,162), and Chad (27,597). In 2024, the figures increased more than eightfold, as according to UN DESA (2025), the emigration stock increased steadily from 978,700 in 2010 to 1.4 million in 2015. It increased further to 1.8 million in 2020 and 2.1 million in 2024 (ibid).

The increase in the number of emigrants is a clear indication of the increasing desire of most Cameroonians to leave the country. It is important to note that high-skill professionals like engineers, teachers, and doctors, as well as high-performing students, constitute a reasonable percentage of those who emigrate. According to Tande (2006), as cited by Ache (2016), 25% to 30% of experts trained in Cameroon migrate, while 70% to 80% of Cameroonians trained abroad do not return to their country of origin. Ache (2016:36) further stated that the Ministry of Health reported that 5,000 Cameroonian-trained medical doctors were living abroad and that only 4,200 are still residents in the country. The report indicates that although there is a higher need for trained medical doctors in Cameroon, as the doctor-patient ratio is significantly lower compared to Europe, there are more trained Cameroonian medical doctors abroad than in the country. This represents a serious health challenge for the healthcare sector.

Labour Migration/Brain Drain

Cameroon is a member state of the Communauté Economique et Monétaire de l’Afrique Centrale (CEMAC), which is a regional body that has ratified the free movement agreement. This means there is a free visa policy that allows nationals of CEMAC’s member states to move with the block’s borders. This initiative, finalised in 2017 by all the member states, has facilitated the movement of labour migrants within the regional block.

According to Nguindip (2018), immigrant labour constitutes 10% of the workforce in Cameroon, Chad, and Gabon. Most immigrants concentrate in dirty, dangerous, and demeaning (3D) jobs where protection is often inadequate or absent. Although the law grants labour migrants equality with nationals, in terms of the treatment of migrant labourers, depending on their skills and profession, this is not true in practice as labour migrants face a variety of employment restrictions. While unskilled migrants, especially undocumented migrants, are subjected to exploitation and violation of their rights, professional and skilled migrants, are protected by migration policies (ibid). The dichotomy of who is deserving and who is not deserving of protection only increases the vulnerability of migrants, especially within the informal sector.

Unauthorised Migration/Trafficking and Smuggling

Cameroon is ranked a Tier 2 country in the Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report (2024) as the government does not meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking (US Department of State, 2024). However, it has made some significant efforts. Cameroon is still a source, a place for transit, and a destination for children subjected to forced labour and sex trafficking. Even though pandemic-related border closures have reduced the number of trafficked victims abroad, the economic impact of the pandemic combined with the ongoing crisis in the North-West and South-West regions has contributed to a sharp increase in the number of victims exploited domestically (US Department of State, 2023). The five years of school closure in the regions have resulted in parents sending their children to intermediaries who exploit them for domestic servitude and sex work rather than sending them to school. Criminals coerce women, IDPs, homeless children, and orphans into sex trafficking and forced labour. Traffickers force children to work in artisanal gold mining, gravel quarries, fishing and animal breeding ventures, or restaurants, or to beg on the streets (US Department of State, 2024).

Foreign business owners and herders force children from neighbouring countries like Benin, CAR, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, and Nigeria to work in spare parts shops or as cattle herders (ibid). During the reporting year (2023), the government reportedly investigated 392 cases, initiated the prosecution of nine alleged traffickers in seven cases, and obtained convictions for four traffickers (US Department of State, 2024). In the 2022 reporting year, the government through the Ministry of Social Development (MINAS) assisted 32 trafficking victims with shelter, basic needs, psychosocial support, health care, and family reunification in its centres in Yaounde, Douala, and Betamba. In 2023, the government did not report assisting any victims (US Department of State, 2023; US Department of State, 2024). However, the facilities were maintained by the government. In 2019, the government provided 2,864 information sessions to help prevent human trafficking, which reached 397,447 people compared to only 69,000 in 2018 (Borgen Project, 2021). Various factors – including poverty and the current Anglophone Crisis in the North-West and South-West regions – increase the vulnerability of Cameroonians being trafficked.

Remittances

Remittances constitute one of the main income sources for many Cameroonian households. According to the World Bank (2025), personal remittances received in Cameroon experienced a steady increase from 2015, when it stood at $241,706,990 to $355,550,646 in 2019. There was a slight decrease in 2020 when it dropped to $334,097,289, and a sharp increase in 2021 when it increased to $430,097,112 and further to $562,660,764 in 2022 and $786,560,478 in 2023 (ibid). Although remittance flow as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Cameroon (0.9%) is not as colossal as in other African countries like Comoros (10%), Senegal (8.4%), Togo (6%), and Ghana (7%), remittance flow in Cameroon contributes to poverty reduction. The transfers enable thousands of households to access necessities like health care services, education, housing, and food supplies (African Media Agency, 2022; Sangu, 2022). One of the challenges that remitters face is the cost of transactions, often arising because of inadequate financial institutions, particularly in rural communities. Households that receive the flow of remittance in Cameroon usually experience improved living conditions.

Returns and returnees

The outbreak of the Anglophone Crisis in the North West and South West regions in 2014 contributed enormously to the displacement of thousands of Cameroonians within and outside the country. Although the situation is still volatile, some of those displaced because of the crisis are gradually returning to their communities. Under the joint EU-IOM Migrant Protection and Reintegration Programme, more than 5,450 Cameroonian migrants have been assisted with their return and reintegration process within their home communities from 2017 to 2021 (IOM, 2021). Their reintegration process is complex and challenging and includes accessing documentation and establishing a proposed business project approved and supported by the joint EU-IOM initiative.

According to the United Nations (2022), because of the high cost of hosting returnees in hotels, the government, in collaboration with IOM, has provided a transit centre in Yaoundé that can accommodate 45 returnees for 72 hours or at most one month for those whose communities do not help with their return (United Nations, 2022). In the transit centre, returnees are provided with psychosocial support activities. The Anglophone Crisis in the North West and South West regions, characterised by the destruction of properties and sources of livelihoods, has created uncertainty among returnees, making their reintegration process in some cases unattainable. It is important to note that there are also independent returnees who are not supported by the government or any non-governmental organisation.

International and civil society organizations

The most important international organisation dealing with migration-related matters in Cameroon is the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which coordinates, protects, and helps persons of concern in collaboration with the government and its partners. The UNHCR’s implementing partners in Cameroon include the International Medical Corps, which works in refugee camps implementing health care programmes that include disease surveillance, nutrition activities, gender-based violence response, mental health and psychosocial support, and child protection. African Humanitarian Action provides refugees with comprehensive health care, nutrition, and infrastructural development services. Plan International ensures children have access to protection, quality inclusive education, health care information and services, and decent work for disadvantaged community members and refugees. Other UNHCR agencies in Cameroon include the World Food Programme, which provides food assistance to communities affected by disasters, including refugees and IDPs, returnees and host communities, and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which provides voluntary return and reintegration programmes to stranded Cameroonians abroad and which focuses on migration policies and research.

Ache, A. I. 2016. The impact of migration and brain drain in Cameroon (Master’s thesis). Estonia, Tallinn University of Technology. Retrieved from: https://digikogu.taltech.ee/et/Download/1f2aff28-2115-4200-ae7c-88f059e805ab

ACP Observatory on Migration. 2013. Internal migration in Cameroon: Constraint for or driver of urban and health development? Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/books/internal-migration-cameroon-constraint-or-driver-urban-and-health-development

African Media Agency. 2022. Will remittance trends from 2022 in Cameroon continue in 2023? Retrieved from: https://africanmediaagency.com/will-remittance-trends-from-2022-in-cameroon-continue-in-2023/

Borgen Project. 2021. 5 facts about human trafficking in Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://borgenproject.org/human-trafficking-in-cameroon/

CIA World Factbook. 2025. Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/cameroon/

Fomekong, S.T. 2021. The implementation of the Kampala Convention in Cameroon: Trends, challenges and opportunities. African Human Rights Yearbook, 93-115. http://doi.org/10.29053/2523-1367/2021/v5a5

Retrieved from: http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/ahry/v5/06.pdf

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2022. Country profile: Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/cameroon

International Crisis Group. 2022. Cameroon’s Anglophone conflict: Children should be able to return to school. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/cameroon/cameroons-anglophone-conflict-children-should-be-able-return-school

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2021. Migrant return and reintegration: Complex, challenging, crucial. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/cameroon/migrant-return-and-reintegration-complex-challenging-crucial

Macrotrends. 2023. Cameroon immigration statistics 1960-2023. Retrieved from: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/CMR/cameroon/immigration-statistics

Mberu, B. & Pongou, R. 2012. Crossing boundaries: Internal, regional, and international migration in Cameroon. International Migration, 54(1):100-118. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264215345_Crossing_Boundaries_Internal_Regional_and_International_Migration_in_Cameroon

Migration Data Portal. 2021. Profile: Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/

Nguindip, C.N. 2018. The right to non-discrimination and the protection of foreigners status within the CEMAC sub-region: The case of Cameroon, Chad, and Gabon. Journal of Human Rights Law and Practice, 1(2):46-58. Retrieved from: https://www.openacessjournal.com/abstract/432

Nyamnjoh, F. 2011. Cameroonian bushfalling: Negotiation of identity and belonging in fiction and ethnography. American Ethnologist, 38(4):701-713. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41410427

Rabat Process. 2028. Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.rabat-process.org/en/countries/76-cameroun.

Sangu, B.F. 2020. The role of remittances in the economic development of Cameroon. Florya Chronicles of Political Economy, 8(2):255-278. Retrieved from: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/2558513

Transparency International. 2022. Corruption Perception Index: Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022

UN Development Programme (UNDP). 2023. Human development insights. Retrieved from: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/country-insights

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2017. Humanitarian action for children: Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/53316

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/91879

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023a. Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/cmr

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023b. Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/cameroon.html

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/cmr

UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2013. Migration profiles: Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://esa.un.org/miggmgprofiles/indicators/files/Cameroon.pdf

UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2019. More than 855,000 children remain out of school in North-west and South-West Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/more-855000-children-remain-out-school-north-west-and-south-west-cameroon

UN Women. 2010. Unleashing the potential of women informal cross border traders to transform intra-African trade. Retrieved from: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2010/3/unleashing-the-potential-of-women-informal-cross-border-traders-to-transform-intra-african-trade

United Nations. nd. Cameroon: Migration profile: Retrieved from: https://esa.un.org/miggmgprofiles/indicators/files/Cameroon.pdf

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2025. Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/

US Department of State. 2021. Trafficking in Persons Report: Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-trafficking-in-persons-report/cameroon/

US Department of State. 2022. Trafficking in Persons Report: Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/cameroon/

US Department of State. 2023. Trafficking in Persons Report: Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/cameroon/

US Department of State. 2024. Trafficking in Persons Report: Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/cameroon/

World Bank. 2025. Personal remittances, received (current $US) – Cameroon. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BM.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT?locations=CM

World Bank Group. 2018. Cameroon city competitiveness diagnostic: Social, urban, rural, and resilience global practice. Retrieved from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/838941529565340570/pdf/Cameroon-City-Competitiveness-Diagnostic.pdf