INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Angola, a resource-rich country in southern Africa, has a complex and evolving relationship with migration, shaped by historical events, economic trends, and political factors. Following years of colonial rule and a lengthy civil war, Angola has faced significant challenges in its post-war reconstruction and economic diversification. These efforts have led to notable population shifts, both internally and through interactions with neighboring countries. Angola's rich natural resources, particularly oil and diamonds, have historically attracted international labor and investment, creating waves of both legal and irregular migration. This influx, coupled with Angola’s limited infrastructure to manage large-scale migration, has led to challenges in controlling borders and providing adequate services to migrant communities. In recent years, Angola has seen increasing migration pressures from neighboring countries, particularly as economic conditions worsen in other parts of the region. The Angolan government has worked to address these migration issues through policy changes, border control enhancements, and collaborations with international organizations. However, challenges remain, especially regarding the integration of migrants and addressing humanitarian concerns linked to irregular migration. Today, Angola’s approach to migration reflects a balance between attracting skilled labor to support its economy and mitigating the social, economic, and security implications of uncontrolled migration flows.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The history of Angola is skewered by the legacy of a protracted civil war and an economy disproportionately dependent on oil. The civil war took place from 1975 to 2002, but Angola has maintained some level of political stability since the end of the 27-year-long civil war that saw more than half a million fleeing from the country. In addition to being a country of origin, destination, and transit for migrants, Angola has seen the return of more than 360,000 Angolans who fled the country during the civil war and four million internally displaced persons who have returned to their communities (UNHCR, 2005). The war lasted for 27 years partly because of the presence of oil and diamond in Angola and the access to these resources by the two contesting rebel movements, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), which financed the war (Frynas, G. & Wood, G, 2001). After the war, oil production in Angola continues to play a very central role in rebuilding the country.

USSR Ambassador to Luand V.P. Loginov, Chief Military Advisor to Angola Colonel General K.Ya Kurochikin, Angolan Defense Minister Colonel Pedro Maria "Pedale" Tona, Head of the Cuban Military Mission to Angola Division General Leopoldo "Polo" Cintra Frías, 1983. Source: Wikimedia Commons / Mil Ru.

According to the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) (2022), Angola is the second-largest oil-producing country in Sub-Saharan Africa, and the country produces approximately 1.16 million barrels of oil per day (US Department of Commerce, 2022). The oil sector accounts for one-third of GDP and more than 90% of exports (Ibid). The historical oil price decline that saw a 70% price drop between mid-2014 and early 2016 (World Bank, 2018), coupled with the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in 2019, has had a devastating effect on the economy of Angola as the economy sank into a recession from 2016 – 2021 (African Development Bank, 2021). However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, created massive oil shortages around the world that hiked oil prices – benefiting Angola as the price increases spurred GDP growth in the country (African Development Bank Group, 2022). Notwithstanding the economic gains, multidimensional poverty (see the section on internal migration), is one of the key drivers of migration and is still a measure of concern in Angola, as more than 50% of the youth are unemployed (The World Bank, 2023a). The history of migration in Angola is intricately linked to its natural resources as the presence of natural resources has been a curse (prolonging the civil war and causing massive displacement) and a blessing (helping in the reconstruction of the country) to the country.

MIGRATION POLICIES

MIGRATION POLICIES

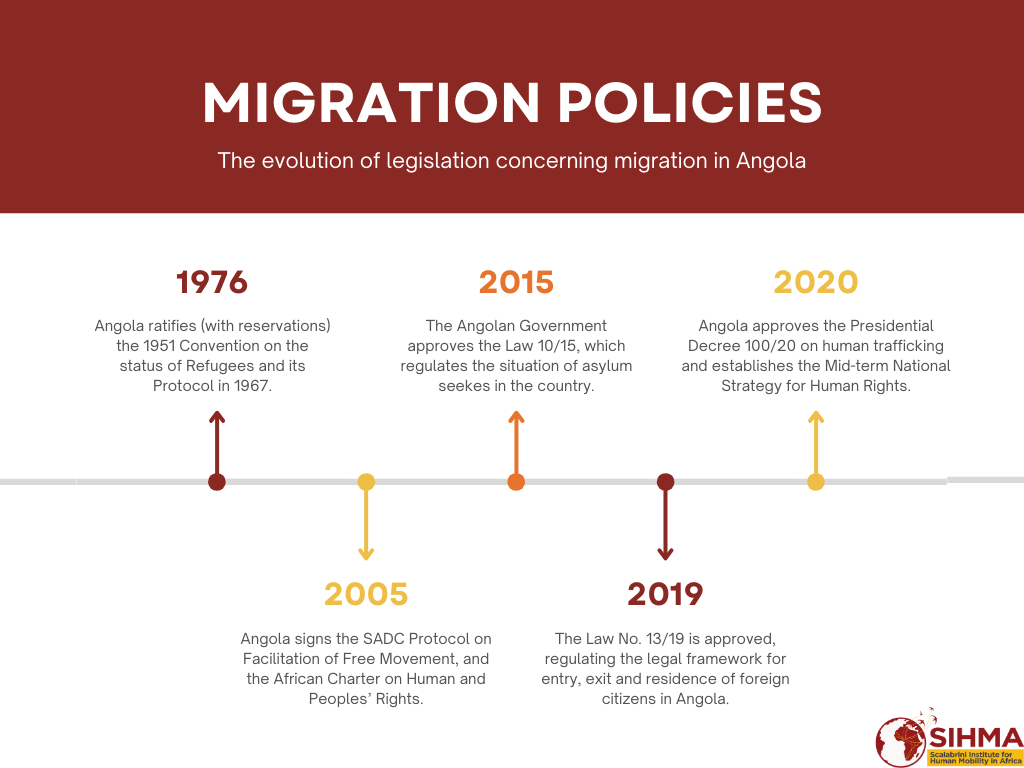

Migration into Angola is mainly governed by three pieces of legislation:

Law No 13/19 of 23 May 2019

The most important piece of legislation governing immigration and emigration in Angola is Law No 13/19 of 23 May 2019, which regulates the legal regime of exit, entry, and residence of foreign citizens in Angola (Republic of Angola, 2019).

Presidential Decree 100/20

In terms of human trafficking, Presidential Decree 100/20 established the Mid-term National Strategy for Human Rights (2020-2025), outlining several measures, including the elaboration of the National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking and the creation of referral mechanisms to assist victims (Presidential Decree 31/20), while Law 1/20 provides for a database on trafficking and the approval of victim protection law (IOM, 2021).

Law 10/15

The government of Angola initiated a new refugee and asylum law in 2015: Law 10/15. This law obliges the state to provide reception centres in which new asylum seekers will be required to stay during the entire asylum process (UNHCR, 2019). So far, this measure has not been implemented as many refugees lack documents and find it difficult to access their rights.

Timeline of Migration Policies in Angola. Source: SIHMA

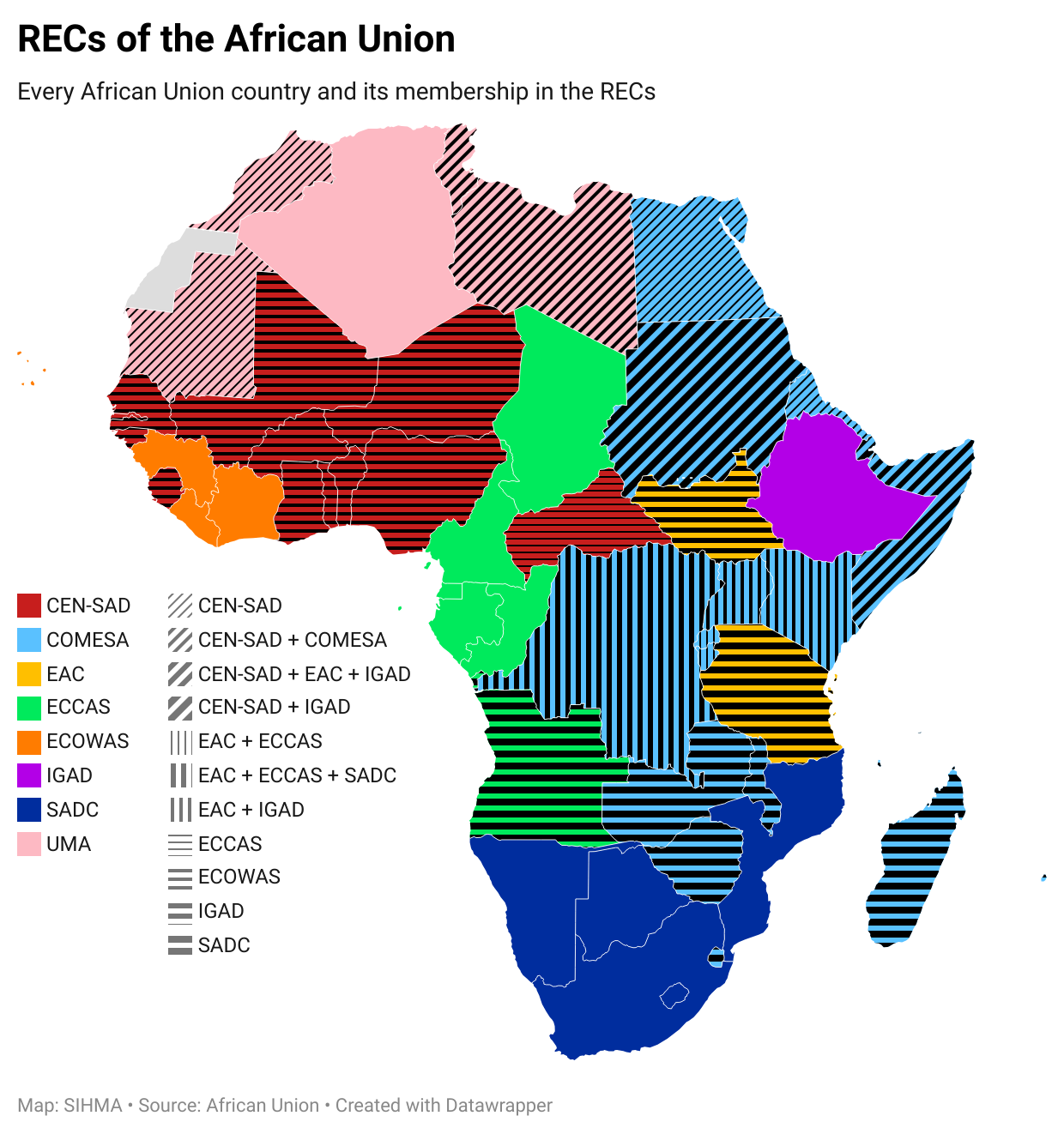

Angola is a signatory to several migration-related international conventions. For example, Angola signed and ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention relating to the status of refugees and its 1967 protocol, as well as the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugees Problems in Africa. Angola has also ratified the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (also called the Kampala Convention), the SADC Protocol on the Facilitation of Movement of Persons (2005), and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (also called the Maputo Protocol). Angola is also a signatory to the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea, and Air, which supplements the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime.

GOVERNMENTAL INSTITUTIONS

GOVERNMENTAL INSTITUTIONS

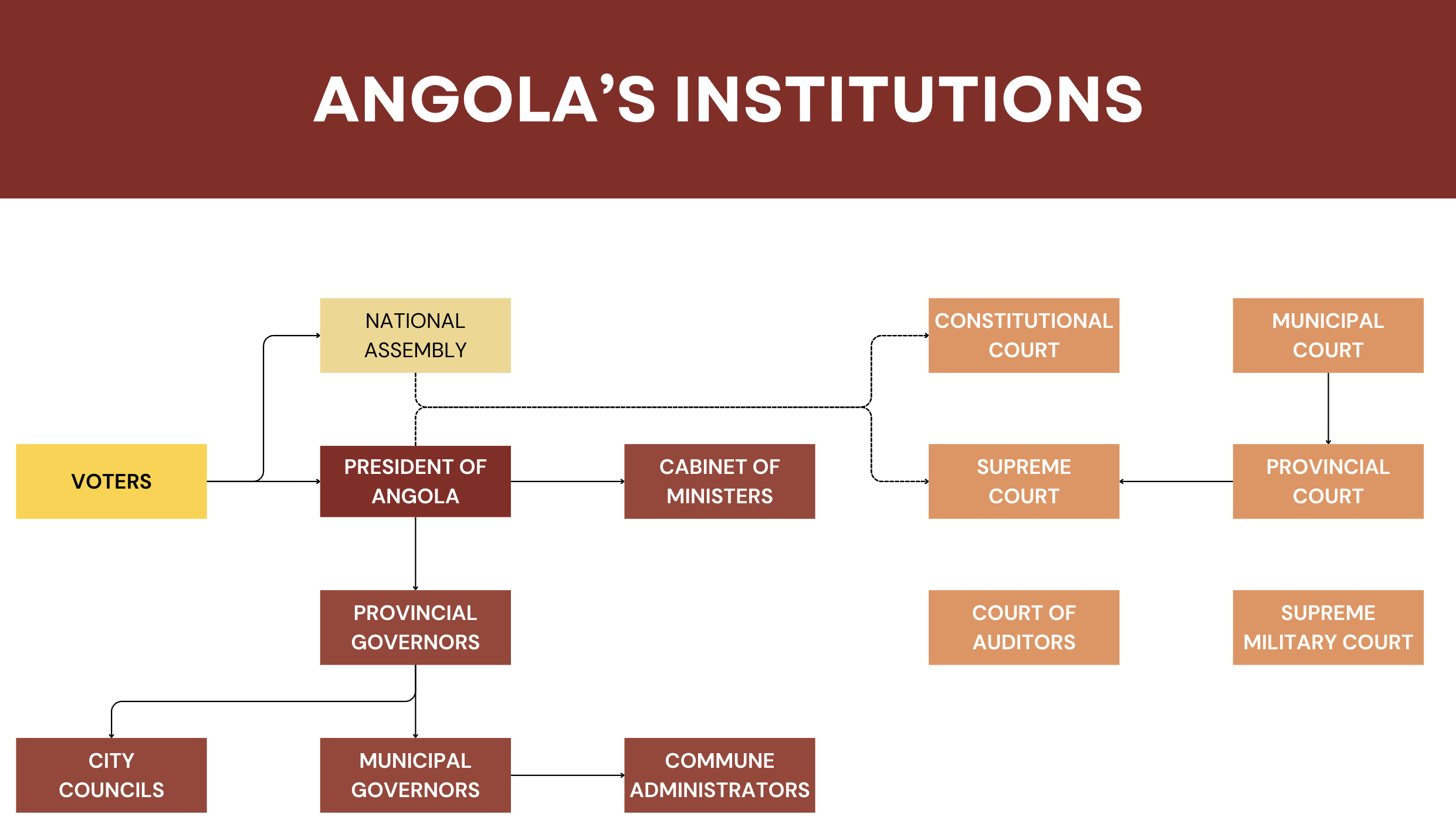

The country’s immigration policy enacted by the Migration and Foreigners Service (SME) is under the Ministry of the Interior. The SME is tasked with promoting, coordinating, and implementing measures related to the transit, entry, stay, residence, and exit of migrants, along with border surveillance. The SME also led the processes that birthed the Angolan Migration Policy (AMP) which focuses on the management of migration flows; the study of migration trends; the integration of migrants and reintegration of nationals; the collection, analysis, and publication of migration data; the analysis of the effect of climate change on migration policies; the promotion of tourism; the engagement of the diaspora; the return of qualified nationals; and the prevention of transnational crime (IOM, 2021).

Angola's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

• Migration and Foreigners Services (SME) website here

• Ministry of Internal Affairs website here

• The Ministry of Foreign Affairs website here

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MIREX) assists Angolan communities abroad and supports the reintegration of Angolan nationals returning home (ibid).

In line with the new refugee law (Law 10/15), in 2018, the National Council for Refugees (CNR) was created, replacing the Committee on Recognition of the Right of Asylum (COREDA) (UNHCR, 2019). The CNR is responsible for Refugee Status Determination (RSD) in Angola.

INTERNAL MIGRATION

INTERNAL MIGRATION

Internal migration in Angola is mostly from rural to urban areas. This migration trend is mainly driven by inadequate infrastructural development, unemployment, and inadequate provision of basic social services in rural areas. Poverty is a main concern in Angola, with 55.3% of Angolans experiencing multidimensional poverty (monetary poverty, and lack of education and basic infrastructure services) (UNDP, 2023). The incidence of multidimensional poverty in rural areas (88% – that is, 9 in 10 people are multidimensionally poor) is far higher than the incidence in urban areas (35% – that is, 1 in 3 people is multidimensionally poor) (ibid). According to the World Bank (2023), youth unemployment in the country exceeds 50%. People are, therefore, leaving the rural areas for urban areas such as Luanda in search of opportunities (Tvedten, 2018). According to UN-Habitat (2023), the urban population rate in 2018 stood at 65.5%, while the urban growth rate between 2015 and 2020 stood at 4.32%.

With the skewed infrastructural development projects concentrated mostly in the urban areas, rural-urban migration precipitated by the search for economic and social opportunities will continue to take place in Angola at a very high rate.

INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS, CONFLICT AND DISASTERS

INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS, CONFLICT AND DISASTERS

Internal displacement in Angola has changed. Before the declaration of independence until the end of the civil war, the main driver of displacement was conflict. During this time in Angola’s history, 13 million people were displaced. Currently, natural disasters have become the main triggers for internal displacement.

2,388,703 Internally Displaced Persons in Angola (2023)

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) (2023), in 2022, there were 1,800 disaster-related displacements in Angola caused by floods and storms. According to the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operation (ECHO) (2023), Angola has recorded casualties and displacements because of heavy rains that have affected several provinces (Luanda, Namibe, Lunda Norte, Lunda Sul, Malanje, Cuanza Norte and Moxico) in the country. On 24 April 2023, media reports indicated that more than 4,380 homes were damaged and approximately 44,000 people were affected – some displaced (ECHO, 2023). Also, on 19 and 20 April 2023, the government reported 708 displacements in the province of Bengo caused by heavy rain (IDMC, 2023). On 24 and 26 October 2023, the government reported that 682 people experienced flood-related displacements in Calandula while 150 people were displaced in Menongue because of a storm (Angop, 2023; Journal de Angola, 2023). Recently, in October and November 2024, floods displaced 159 people in Luanda Norte and 300 people in Longonjo (IDMC, 2025). The susceptibility of the country to disaster-related displacements is premised on the fact that there are limited mitigating circumstances that can effectively manage severe weather events like early warning systems and adequate infrastructure.

IMMIGRATION

IMMIGRATION

Angola’s oil and diamond wealth has been a force of attraction for international migrants, both skilled and unskilled. Angola is one of the three countries hosting the highest number of international migrants in the sub-region, the other two countries being South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo, (Southern Africa). By mid-2020, Angola hosted 656,434 international migrants (Migration Data Portal, 2021). Economic migrants, which are those arriving for business, come by air while a large mass of migrants come via land from the DRC. They use boats, and walk long hours, across forests and rivers. The top five countries of origin of international migrants in Angola are the Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Cabo Verde, Sao Tome, and Principe (UN DESA, 2019).

In Angola, migrants from the Democratic Republic of Congo constitute more than 75% of all international migrants by country of origin (ibid). The challenges that international migrants face include difficulties with proper documentation, which restrain them from enrolling their children in schools, opening bank accounts, making their businesses more profitable, and accessing public services, especially health care. Its rich mineral resources (oil and diamond) position the country as a place of opportunity – attracting international migrants from within and outside the continent.

FEMALE MIGRATION

FEMALE MIGRATION

Over the past two decades, the share of international female migration stock has experienced a steady increase in Angola. For example, according to UN DESA, as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), there were an estimated 22,700 female international migrants in Angola in the year 2000. By 2010, the numbers increased to 174,400, and by 2020, it stood at 325,000 – representing 49.5% of the total international migration stock. Some female migrants in Angola have been subject to repeated attacks, stigmatisation, and abuse of their human rights. In 2014, within 10 days, 3,000 people, including women and children, were rounded up in Luanda and kept in deplorable conditions while some were forcefully deported (International Federation for Human Rights, 2014). Recently, during an expulsion operation of Congolese migrant workers, it has been reported that the Angolan security forces raped women and children in the process (Human Rights Watch, 2023). The vulnerability of female immigrants in the country especially in the hands of those who are meant to protect them raises fundamental questions about the rule of law and the respect for human rights in the country.

MINORS

MINORS

Angola is one of the top ten countries in the world with the highest number of child migrants (18 years or younger), and in 2017, the country hosted 302,000 migrant children (Gadisa et al., 2020). According to UN DESA, as cited by the Migration Data Portal (2021), of the 656,400 international migrants in Angola, 21.4% (140,470) were children 19 years or younger. While there is a significant presence of migrant children in Angola, there is a remarkable number of unaccompanied migrant children in the country.

656,400 Migrant Minors in Angola (2021)

According to a report from UNICEF, 200 unaccompanied children were fleeing from the war in Congo and arrived in reception camps in Angola (UNICEF, 2017). Although the Angolan Children’s Act, in principle, provides that a child should only be detained as a measure of last resort and such detention should follow international standards, in practice, during round-up operations, pregnant women and children are arrested and detained (see section on Female Migration) (Gadisa et al., 2020). Child migrants in Angola are also subject to forced deportation. For example, in 2018, UNICEF reported that 80,000 children were among the Congolese migrants expelled by the government (ibid). The disjuncture between the law and the lived experiences of children further increases the vulnerability of children, especially unaccompanied minors.

REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS

As a result of the protracted civil war in Angola (1975 – 2002), the country has been known as a refugee-origin country. However, after the war, Angola has also become a refugee-receiving country. In January 2025, there were 25,295 refugees and 30,279 asylum seekers in Angola (UNHCR, 2025). Most of the refugees and asylum seekers in Angola are from the Democratic Republic of Congo. These 22,927 refugees and asylum seekers represent 41.3% of the refugees and asylum seekers in the country (ibid). Other countries with double percentage points of refugees and asylum seekers in Angola include Guinea at 16.7% (9,272), Ivory Coast at 11.4% (6,357), and Mauritania at 10.3% (5,725) (ibid). Refugees and asylum seekers are spread throughout provinces in Angola, with most of them in Luanda (38,271) and Lunda Norte (9,973) (ibid). Other provinces hosting refugees include Moxico (3,135), Lunda Sul (1,315), Malanje (1,067), Bengo (869), Cuanza Sul (221), Cuanza Norte (174), Uige (151), Zaire (139), Bie (122), Cunene (98), Huambo (35), and Cabinda (4) (ibid). The main reason for forced migration, for example from the DRC to Angola, is the political instability in the country. Due to the porous borders that separate most African countries, like the border between Angola and the DRC, it becomes possible for some migrants to be smuggled or trafficked into Angola from the DRC by foot or by bus. While in Angola, refugees and asylum seekers are subject to arbitrary arrest and detention and, in some cases, expulsion (Human Rights Watch, 2023). The current political instability in parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo which is the home country to the majority of the refugees and asylum seekers in Angola means that the movement is going to continue until such a time when stability will be restored in the troubled areas.

EMIGRATION

EMIGRATION

According to the European Union Global Diaspora Facility (2020), about 661,590 Angolan nationals reside abroad. Most of them live in Africa. This represents 2.1% of the Angolan population. The top five countries of destination of Angolan emigrants are the Democratic Republic of Congo (179,065), Portugal (158,958), South Africa (69,659), Congo (42,506), and Namibia (39,580) (ibid). The European Union hosts an estimated 217,428 Angolan emigrants representing 32.9% of the total emigrant population (ibid).

661,590 Angolan Emigrants (2020)

High population growth, high unemployment, and comparatively low salaries for professionals in Angola make the emigration of skilled professionals particularly attractive for these young professionals. For example, even though Angola faces a significant shortage of physicians, with only 3,700 in the country and with a doctor/patient rate of 0.94 doctors per 10,000 population (Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2021), an estimated 70% of all trained physicians in Angola emigrate (Kigotho, 2018). The 2021 Human Flight and Brain Drain in Africa Index indicates that Angola is slightly above the 2021 world average of 5.21 index points. Angola is currently at 5.9 index points (The Global Economy, 2022). Such trends of trained medical professionals emigrating will leave the country with severe understaffing, overcrowded hospitals and vast disparity in access to quality health care.

LABOUR MIGRATION

LABOUR MIGRATION

After a long post-independent war, Angola has enjoyed political stability and peace for more than two decades. This attracts many labour migrants, particularly from neighbouring countries. They typically work in construction and mining or set up private businesses that contribute significantly to the economy. However, because Angola is not a signatory to labour migration-related conventions such as the Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrants Workers and Members of their Families and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, migrant workers are vulnerable to exploitation and inhuman treatment (United Nations, 2016). According to Reuters (2023), mass deportation of labour migrants from Angola is something that happens every few years, with the largest in 2018, which saw the expulsion of 330,000 workers. During such processes of deportation, migrant workers experience human rights abuse, including rape (Africanews, 2023). Besides the vulnerabilities that migrant labourers are exposed to, inadequate protection also adversely affects workplace dynamics as workers are not motivated to work – reducing production levels.

HUMAN TRAFFICKING

HUMAN TRAFFICKING

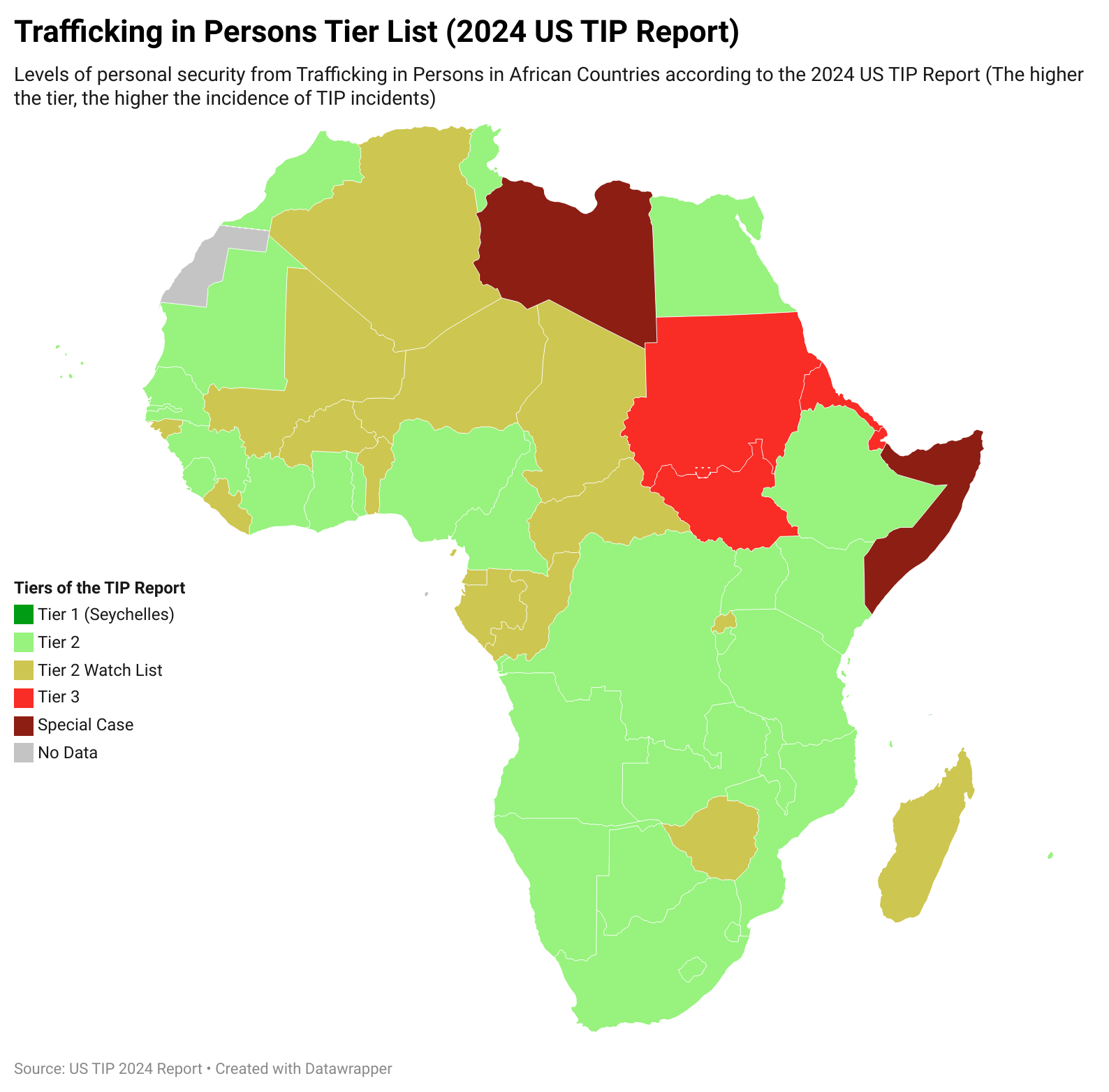

Angola is a Tier 2 country as it does not entirely meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking despite efforts to do so. Poverty and the desire to make quick cash are some of the main drivers of human trafficking in the country. Angola is a source, transit, and destination country for victims of human trafficking, especially women and children as young as 12 years being subjected to forced labour or sex trafficking, and men being subjected to forced labour. The most high-threat areas of human trafficking in Angola are Luanda, Benguela, Cunene, Lunda Norte, Namibe, Uíge, and Zaire (US Department of State, 2024) Other victims of human trafficking come mainly from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In 2023, the government identified 44 trafficking victims (13 victims of labour trafficking, 19 victims of sex trafficking, and 12 victims of unspecified forms of trafficking) from Angola and Vietnam (ibid). All 44 victims (10 children and 44 adults) were referred to services (ibid). In 2023 the government initiated 10 human trafficking investigations (three for sex trafficking, two for labour trafficking, and five for unspecified forms of trafficking), initiated one new prosecution for forced labour, and obtained one conviction for (ibid).

Identified victims were referred to religious or NGO-run shelters for clothing, food, educational support, and medical care. The government provides limited financial support to some of these shelters (ibid). The government under the Ministry of Social Action, Family, and the Promotion of Women manages a national network of safe houses for women, counselling centres and child centres accessible to victims of human trafficking, located in all 18 provinces (ibid). The government also provides victims of human trafficking with access to immigration relief, including temporary residence documents, the right to seek asylum, legal representation, immunity from trafficking crimes, medical and mental health services, some financial support, family tracing assistance, and access to education (ibid). However, the immigration-related benefits are contingent upon the commencement of a criminal investigation and the victim’s testimony.

REMITTANCES, RETURNS AND RETURNEES

REMITTANCES, RETURNS AND RETURNEES

Remittance flow does not contribute significantly to the country’s revenue. It was only in 2008 that remittance flow contributed 0.1% to the country’s GDP. However, the relief of this money is felt profoundly at the household level as it helps to reduce household poverty. For example, a study conducted by IOM (2010) revealed that remittance flow assists households in food, education, and health, with a small proportion of the money re-invested in business-generation activities, business, or asset creation.

According to the World Bank (2023), remittance flow was at its all-time high in 2008 when it stood at $82,084,000. In 2009, it dropped significantly to $162,359 and in 2010 it went up to $17,972,037. In 2011, it dropped steeply to $204,751 and went up significantly again to $40,348,854 in 2012 (ibid).

Remittance flow experienced a steady decline from $36,637,411 in 2013 and $30,971,119 in 2014 to $11,114,712 in 2015, $3,988,048 in 2016, and $1,418,196 in 2017. It started to increase from $1,579,247 in 2018 and $3,445,473 in 2019 to $8,053,051 in 2020, $12,631,149 in 2021, and $14,005,491 in 2022 (ibid).

With the prevalence of multidimensional poverty in Angola, remittance flow contributes enormously to so many households' income. Indeed, fluctuations in such flows create financial instability for those households that depend on it.

African Development Bank Group. 2022. Angola economic outlook. Retrieved from: https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/southern-africa/angola.

African Development Bank. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 in Angola using input-output matrix. Retrieved from: https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/2022/03/24/the_impact_of_the_covid-19_in_angola_using_io_matrix.pdf.

Africanews. 2023. Angola: Illegal immigrants including women, children experience abuses – UN. Retrieved from: https://www.africanews.com/2023/04/13/angola-illegal-immigrants-including-women-children-experience-abuses-un//.

Angop. 2023. Chuva mata criança em Calandula. Retrieved from: https://www.angop.ao/noticias/sociedade/chuva-mata-crianca-em-calandula/.

ECHO. 2023. Angola – Floods (Floodlist media, INAMET). Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/angola/angola-floods-floodlist-media-inamet-echo-daily-flash-24-april-2023.

European Union Global Diaspora Facility. 2020. Diaspora engagement mapping: Angola. Retrieved from: https://diasporafordevelopment.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/CF_Angola-v.4.pdf.

Frynas, G. & Wood, G. 2001. Oil & War in Angola. Review of African Political Economy, Vol.28(90):587-606. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4006839.

Gadis, G., et al. 2020. Migration-related detention of children in Southern Africa: Developments in Angola, Malawi, and South Africa. Retrieved from: https://repository.gchumanrights.org/items/b002a532-3849-4062-817d-a8230004e6fc.

Human Rights Watch. 2023. Angola forces linked to abuses against migrant women. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/04/14/angolan-forces-linked-abuses-against-migrant-women.

IDMC. 2023. Country profile: Angola. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/angola.

International Federation for Human Rights. 2014. Angola: Thousands of African nationals suffer serious human rights violations. Retrieved from: https://www.fidh.org/en/region/Africa/angola/angola-thousands-of-african-nationals-suffer-serious-human-rights.

IOM. 2009. Angola: A study of the impact of remittances from Portugal and South Africa. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mrs39.pdf.

IOM. 2021. Republic of Angola: Migration governance indicator. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/MGI-Angola-2021.pdf. \

Japan International Cooperation Agency. 2021. Data collection survey on the health system in Angola. Retrieved from: https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/1000045911.pdf.

Journal de Angola. 2023. Chuvas torrenciais em Menongue causam 10 feridos. Retrieved from: https://www.jornaldeangola.ao/ao/noticias/chuvas-torrenciais-em-menongue-causam-10-feridos/.

Kigotho, W. 2018. African Union devises 10-year plan to stem brain drain. Retrieved from: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20180209080048133.

Migration Data Portal. 2021. Angola. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/.

OPEC. 2022. Angola. Retrieved from: https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/147.htm.

Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. 2020. Multidimensional poverty in Angola 2020. Retrieved from: https://ophi.org.uk/angola_mpi_2020/.

Republic of Angola. 2019. Angola: Law No. 13 of 2019, law on the judicial regime of citizens in the Republic of Angola. Retrieved from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5d4ab9a74.html.

Reuters. 2023. Dozen raped as migrant workers expelled from Angola to Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/dozens-raped-migrant-workers-expelled-angola-congo-2023-04-13/#:~:text=Mass%20deportations%20from%20Angola%20to,violence%20during%20expulsions%20from%20Angola.

The Global Economy. 2022. Angola: Human flight and brain drain. Retrieved from: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Angola/human_flight_brain_drain_index/.

The World Bank. 2023a. Angola: Overview. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/angola/overview.

The World Bank. 2023b. Personal remittances, received (current US$) – Angola. https://publications.iom.int/books/mrs-no-39-angola-study-impact-remittances-portugal-and-south-africa.

The World Bank. 2023c. Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Angola. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT?locations=AO.

Tvedten, I., et al. 2018. Comparing urban and rural poverty in Angola. https://open.cmi.no/cmi-xmlui/handle/11250/2572392.

UN DESA. 2019. Angola: International Migration Stock. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp.

UNDP. 2023. Briefing note for countries on the 2023 multidimensional poverty index. Retrieved from: https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/Country-Profiles/MPI/AGO.pdf.

UN-Habitat. 2023. Angola. Retrieved from: https://unhabitat.org/angola.

UNHCR. 2005. Angola. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/449267560.pdf.

UNHCR. 2012. End of refugee status for Angolan and Liberian exiles this weekend. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing-notes/end-refugee-status-angolan-and-liberian-exiles-weekend.

UNHCR. 2019. UNHCR country portfolio evaluation: Angola (2016 – 2019). Retrieved from: https://www.itad.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/UNHRC-Angola.pdf.

UNHCR. 2023. Angola. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/ago.

UNICEF. 2017. UNICEF reaches children fleeing to Angola from violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Retrieved from : https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-reaches-children-fleeing-angola-violence-democratic-republic-congo.

United Nations. 2016. UN special rapporteur on the human rights of migrants concludes country visit to Angola. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2016/05/un-special-rapporteur-human-rights-migrants-concludes-country-visit-angola.

US Department of Commerce. 2022. Angola – Country commercial guide: Oil and gas. Retrieved from: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/angola-oil-and-gas.

US Department of State. 2022. Trafficking in person report: Angola. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/angola/#:~:text=TRAFFICKING%20PROFILE,-As%20reported%20over&text=Angolan%20girls%20as%20young%20as,children%20cannot%20be%20criminally%20prosecuted.

US Department of State. 2023. Trafficking in person report: Angola. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/angola/#:~:text=Traffickers%20exploit%20Angolans%2C%20including%20children,and%20artisanal%20diamond%20mining%20sectors