The Exclusion of Migrant Women in Africa | Access to the Labour Market

About the blog series

Studies show that intra African female migration is a growing phenomenon in recent years as more and more women migrate (1). For instance, since 1994, South Africa has received an influx of migrant women from various parts of Sub-Saharan Africa (2) and the proportion of female migrants in Sub-Saharan African has risen from 46.4 in 2005 to 47.5% in 2019 (3). Migrant women represent a particularly disadvantaged group: gender, ethnicity and racial discrimination can lead to a triple disadvantage for migrant women in the host society (4), adding to pre-existing hardships in the broader population.

This article is the first of a series exploring the particular challenges and vulnerabilities of migrant women in Africa that public policies fail to effectively address. In this first blog post in the series, we look at the experience of migrant women in the African labour market.

Migrant women in the African labour market

One of the most vulnerable migrant workers groups are domestic workers, who are overwhelmingly women: 73.4%of migrant domestic workers are women (5). This relates to target 8.8 of the Sustainable Development Goals to “protect labor rights and promote safe and secure working environments of all workers, including migrant workers, particularly women migrants, and those in precarious employment” (6).

Many of the examples used are from South Africa as it is a preferred destination of the majority of African migrants (2) and a well-studied country. In comparison to the situation in their home countries, many migrants perceived South Africa as having a thriving, vibrant and developed economy, where jobs are available (7), despite South Africa having an unemployment rate of 29% (8).

Migrant women are often not perceived from an employment perspective (9). Women’s migration is mainly described from a family perspective, while men’s migration is defined from an employment perspective. Women are viewed as accompanying their husbands and as dependent on men (9). This is reflected in employment: a study conducted in Gauteng, South Africa, showed that there is a lower likelihood of employment for women than for men (10).

Arriving in the country of destination, migrant women rely on coping and adaptation mechanisms to deal with the stress created by acculturation, among which employment plays a central part (7). Coping mechanisms are short-term survival mechanisms used on arrival. First coping options include family support, employment and humanitarian support. On the other hand, adaptation mechanisms – or long-term resilience – are predominantly employment and entrepreneurship. These include formal employment in the public and private sector, informal jobs, as well as surviving through domestic work or farm work or self-employment by trading in retail, hairdressing, vending, cooking on the street etc. Migrant women working as domestic workers are particularly at risk of exploitation and abuse (11).

Coping and adaptation are highly dependent on one’s migratory status. A migrant women with the correct or legal documentation and a formal job will cope and adapt better than an asylum seeker, a refugee or an irregular migrant who must first regularise her stay before she can get formal employment and earn a living (2).

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), restrictions on migration – such as temporary migration schemes – encourage irregular migration, heighten migrants’ vulnerability to exploitation, and push migrants into the informal economy (11). This is particularly true for female migrant workers, who find themselves over-represented in the informal sector and among undocumented workers (12).

Refugees, asylum seekers and irregular migrants may engage in ‘deskilling’ as a coping mechanism in the absence of availability of any suitable job (2). Deskilling means that educated migrants have to rely on or taken on a lower level skill position like physical labour instead of using their intellectual skills to earn a living (2). Labour policies are forcing many migrant women to take any available job by deskilling instead of using their qualifications (7).

For instance in South Africa, Zimbabwean migrant women are likely to work in low-skilled and low-paying jobs, although the majority have completed secondary and tertiary education (11), mainly because of the non-recognition of their foreign qualifications and the prejudices against foreign education in the host country (2). Deskilling is a way for the host country to fill up labour shortages by capitalising on the cheap labour of these migrants, but is also as a deliberate discriminatory move (13). In the long-term, some migrant women, if they have access to education, are able to up-skill themselves to the host country standards to access jobs they are qualified for (2).

89% of women workers are found in the informal sector in Sub-Saharan Africa (14). In their study of female migrants in the informal sector business in the Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana, published in the latest edition of the African Human Mobility Review, Fabian Sebastian Achana and Augustine Tanle revealed that migrant women workers are subject to health and economic rights violation, verbal abuse, physical injury, sexual harassment, unfair labour practice working without sick leave, and with little or no control over their employment conditions (15). This leaves migrant women exploited and abused by customers and employers (15).

The difficulties faced by migrant women are directly connected to the labour policies of both the origin and host countries. In its report on “Decent work for migrant domestic workers: Moving the agenda forward”, the ILO highlights the importance of implementing and enforcing international labour standards at the national level with targeted legislative and policy initiatives by both origin and destination countries to avoid exploitation (11). Examples of effective policies include the setting up of labour desk at international airports, complaint mechanisms and pre-departure training in the origin country, and maternity protection, regularised written work contracts, minimum wage and work hours policies in the host country (11). The report also emphasise the need for better cooperation between countries to regularise work (11).

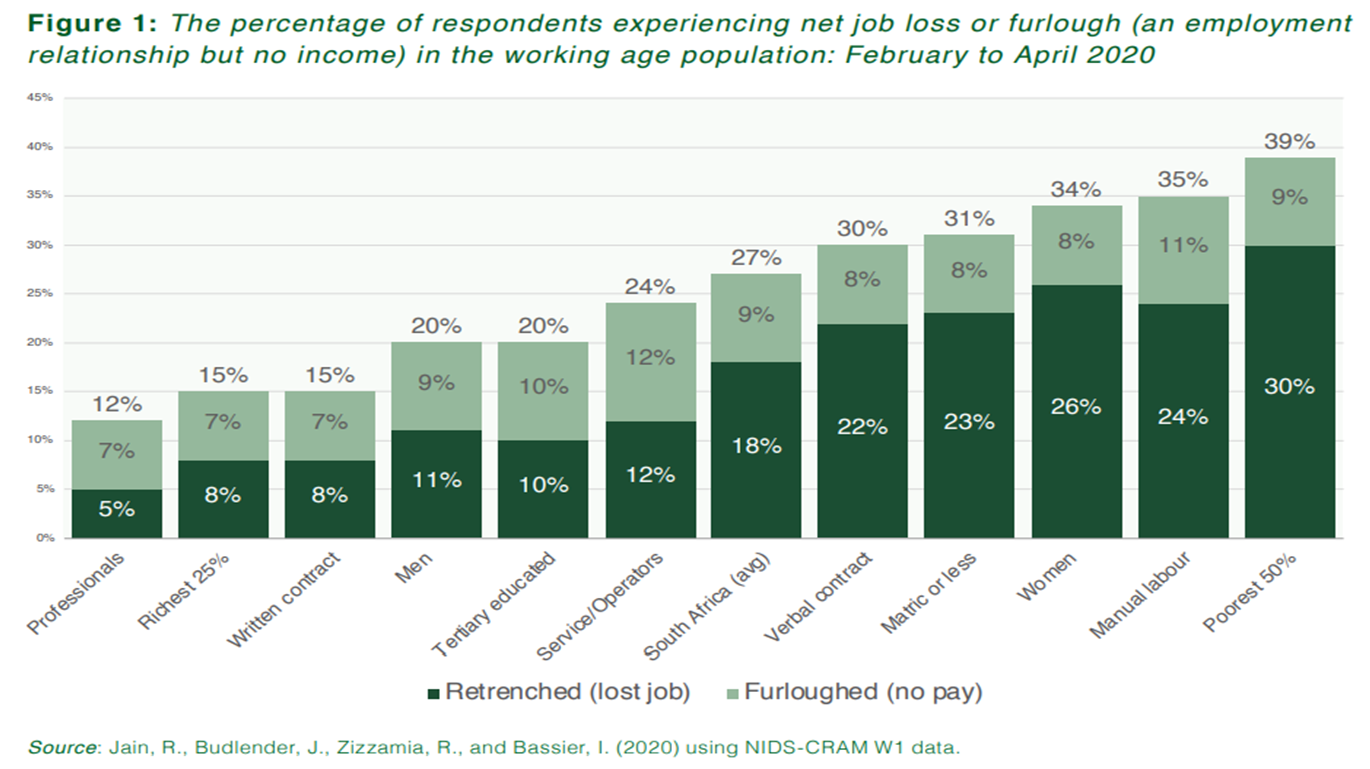

The current Covid-19 pandemic has revealed other existing issues affecting women, and one can assume migrant women as well. The NIDS-CRAM Synthesis Report found that job losses due to Covid-19 were concentrated among the already disadvantaged groups, i.e. women and the poorest 50% (16).

At the webinar on the Impact of Covid-19 on Women and their Businesses hosted by the Delegation of the European Union to South Africa, which SIHMA attended (17), the panel highlighted the particular challenges faced by women in accessing financial support, as well as the burden of increased unpaid work on women who have to take care of their family while continuing to work. These issues are confronting women with more difficulties than men in recovering from the Covid-19 crisis.

One of the key factors preventing women’s work is the lack of access to childcare for mothers who had to continue working when schools and day cares closed under the lockdown. Female employees and entrepreneurs, including migrant women, have to rely on the help of their families and neighbours to care for their children, which creates high levels of anxiety and impacts their ability to work (17).

Another important factor is the lack of available and affordable data and digital technology, which prevents women from finding resources and work opportunities, to access finance and legal support, and, especially during lockdown, to work from home. The lack of data particularly affects rural areas where women are isolated from the broader labour market and lack access to technology, as well as marginalized groups such as migrant women who might not have the means to afford data.

Initiatives such as the Women’s Platform by the Scalabrini Centre of Cape Town are needed to make up for bad policies and to address the isolation of women facing economic hardship, unemployment and exploitation. The Platform is “a network where women can facilitate connections, share knowledge and resources, and access opportunities” (18). Migrant women are provided with network opportunities and training, with two areas of focus: personal development and financial sustainability.

Migrant women, especially in the informal sector, also have particular health concerns and social needs (15). We invite you to keep an eye on our following article that will address migrant women’s lack of access to healthcare services.

James Chapman and Nolwenn Marconnet

SIHMA SIHMA

Project Manager Research and Communication Intern

Resources

- UNCTAD, Economic Development in Africa Report 2018 Migration for Structural Transformation Background Paper Intra-African Female Labour Migration. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/edar2018_BP1_en.pdf

- Ncube, A. (2017). The socio-economic coping and adaptation mechanisms employed by African migrant women in South Africa. https://scholar.ufs.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11660/7732/NcubeA.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) (2019). International Migrant Stock Graphs: 2019 UNDESA Population Division. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimatesgraphs.asp?4g4

- Piper, N. (2006). Gendering the politics of migration. International Migration Review 40(1), 133-164. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00006.x

- UN Women (2020). Migrant workers. https://interactive.unwomen.org/multimedia/infographic/changingworldofwork/en/index.html

- SDG Compass (2015). SDG 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. https://sdgcompass.org/sdgs/sdg-8/

- Ncube, A., Bahta, Y.T., Jordaan A.J. (2019). Job Market Perceptions of African Migrant Women in South Africa as an Initial and Long-Term Coping and Adaptation Mechanism. Journal of International Migration and Integration. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-019-00704-w

- STATS SA (Statistics South Africa). (2019). Unemployment rises slightly in third quarter of 2019. Pretoria: South Africa. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=12689

- Kraler, A., Bonjour, S., Cibea, A., Dzhengozova, M., Hollomey, C. and Reichel, D. 2011. Migrants, minorities and employment – Exclusion and discrimination i the 27 member states of the European Union (Update 2003-2008). European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. http://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2011/migrants-minorities-and-employment-exclusion-and-discrimination-27-member-states

- Thoka, M., Geyer, H.S. (2019). Migration and labour force participation: an analysis of internal economic migrants in Gauteng, South Africa, 2011. South African Geographical Journal, 101:3, 307-325, DOI: 10.1080/03736245.2019.1612771 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03736245.2019.1612771?needAccess=true#aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cudGFuZGZvbmxpbmUuY29tL2RvaS9wZGYvMTAuMTA4MC8wMzczNjI0NS4yMDE5LjE2MTI3NzE/bmVlZEFjY2Vzcz10cnVlQEBAMA==

- Tayah M.-J. (2016). Decent work for migrant domestic workers: Moving the agenda forward. International Labour Office, Conditions of Work and Equality Department. Geneva: ILO http://www.oit.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_535596.pdf

- International Labour Organisation (ILO) (2020). Protecting migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recommendations for Policy-makers and Constituents. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_743268.pdf

- Siar, S.V. (2013). From highly skilled to low skilled: Revisiting the deskilling of migrant labour. Philippine Institute for Development Studies. http://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/ris/dps/pidsdps1330.pdf

- UN Women (2020). Women in informal economy. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/women-in-informal-economy

- Achana, F.S., Tanle, A. (2020). Experiences of Female Migrants in the Informal Sector Businesses in the Cape Coast Metropolis: Is Target 8.8 of the SDG 8 Achievable in Ghana? AHMR African Human Mobility Review - 6: 2. http://sihma.org.za/journals/03%20Experiences%20of%20Female%20Migrants%20in%20the%20Informal%20Sector%20Businesses.pdf

- National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM) (2020). Overview and Findings NIDS-CRAM Synthesis Report Wave 1. https://cramsurvey.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Spaull-et-al.-NIDS-CRAM-Wave-1-Synthesis-Report-Overview-and-Findings-1.pdf

- Scalabrini Institute for Human Mobility in Africa (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on women and their businesses. http://sihma.org.za/Blog-on-the-move/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-and-their-businesses

- Scalabrini Centre of Cape Town (2020). The Women’s Platform. https://scalabrini.org.za/service/womens-platform/

Categories:

Tags: